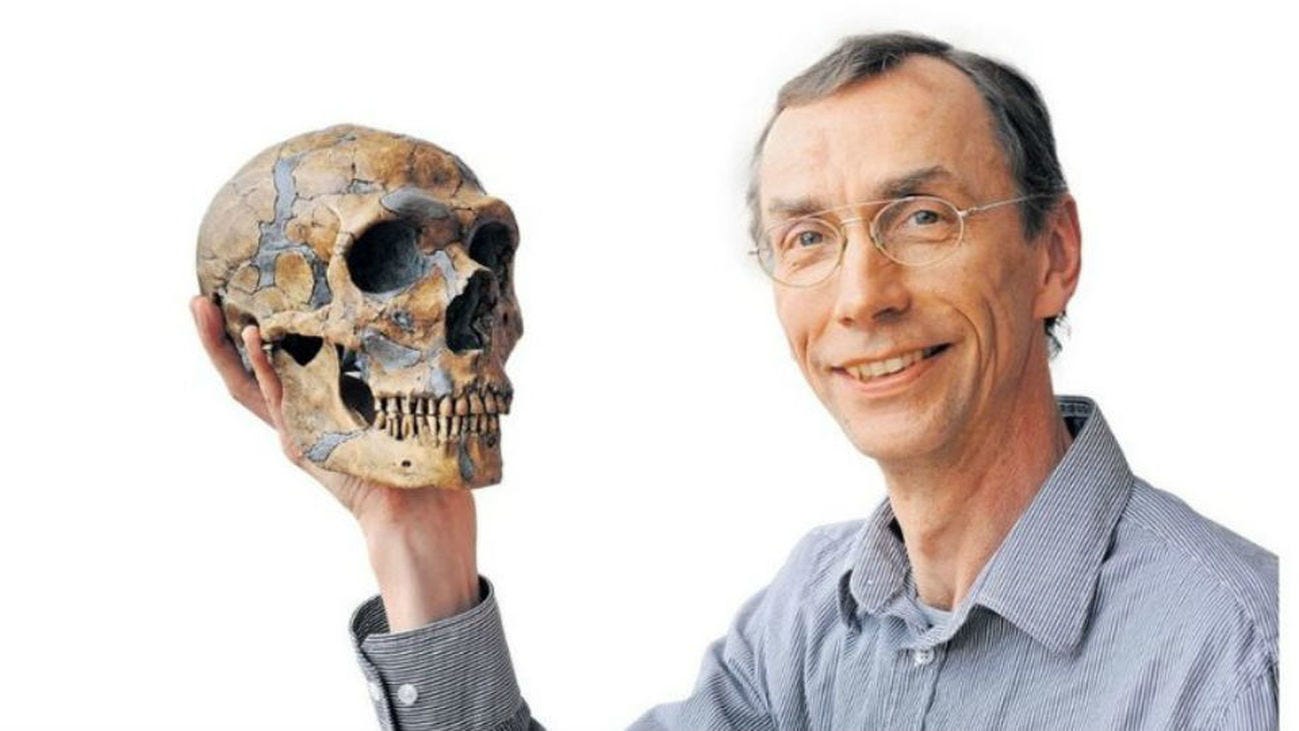

Svante Pääbo Awarded Nobel Prize

The Neanderthal DNA sequenced by a Swedish researcher received recognition for his efforts.

Since the first Neanderthal remains were discovered in a German quarry in 1856, paleontologists have struggled to understand what separated those primitive humans from modern ones, and how did they relate to us?

Svante Pääbo, a scientist of Swedish descent whose decades-long efforts to extract DNA from 40,000-year-old remains culminated in th…