Brains of Neanderthal & Human Share A Startlingly "Youthful" Characteristic

Particularly, strong cerebral cortical integration into maturity is a shared trait between humans and Neanderthals.

Many people think that the fact that we have such enormous brains is what makes us human, but is there more to it? The shape of the brain and the lobes that make up its constituent portions may also be significant.

The findings of a study1 that was published in Nature Ecology & Evolution demonstrate how the human brain's many components evolved differently from our primate ancestors and in summary, our brains essentially never mature. The Neanderthals are the only other primate with which we share this "Peter Pan syndrome." The discoveries further blur the line between us and our extinct ancestors while also shedding light on what makes us human.

The scientists looked for evidence that the evolution of the brain's lobes are "integrated," meaning that changes in one lobe appear to be inevitably linked to changes in others, or that the lobes evolved independently of one another. They were especially interested in how human brains might differ from those of other primates in this regard.

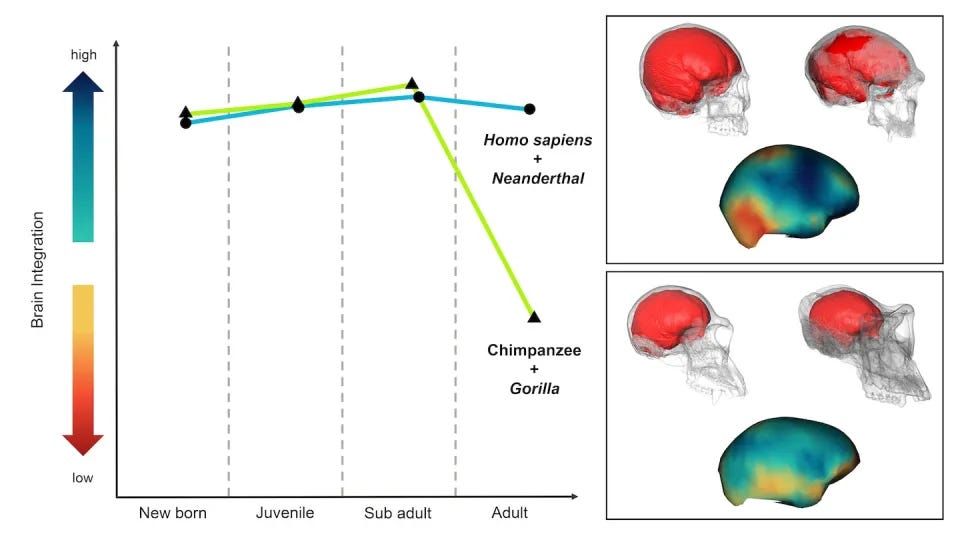

Examining how the various lobes have evolved through time in various species and determining how much each lobe's form has altered in relation to others can help answer this question. As an alternative, one can gauge how much the brain's lobes integrate with one another as an animal progresses through its many life phases.

Does a change in the form of one area of the developing brain correspond to a change in another area? Because evolutionary steps can frequently be tracked through an animal's development, this can be instructive. The brief presence of gill openings in early human embryos is a typical illustration, highlighting the fact that we may trace our evolutionary history back to fish.

The writers employed both techniques.

As well as humans and our near fossil ancestors, the first analysis included 3D brain models of hundreds of live and extinct primates, including monkeys, apes, and living primates. This enabled them to chart the evolution of the brain throughout time.

They were able to illustrate how the various components of the brain integrate as different species mature using the other digital brain data set, which included living ape species and humans at various maturation phases. The brain models were created using CT scans of human skulls, and by digitally filling in the brain cavities, the form of the brain was roughly approximated.

The findings were surprising. They discovered that humans had exceptionally high degrees of brain integration, notably between the parietal and frontal lobes, by tracking change over long stretches of time across dozens of monkey species. But they also discovered that we're not alone. In Neanderthals as well, there was a significant degree of integration between these lobes.

Up until puberty, the integration of the brain's lobes in apes, like the chimpanzee, is similar to that of humans, according to research on shape changes that occur during development. The apes' integration rapidly declines at this point, whereas in humans, it persists long into adulthood.

What does all of this mean, then?