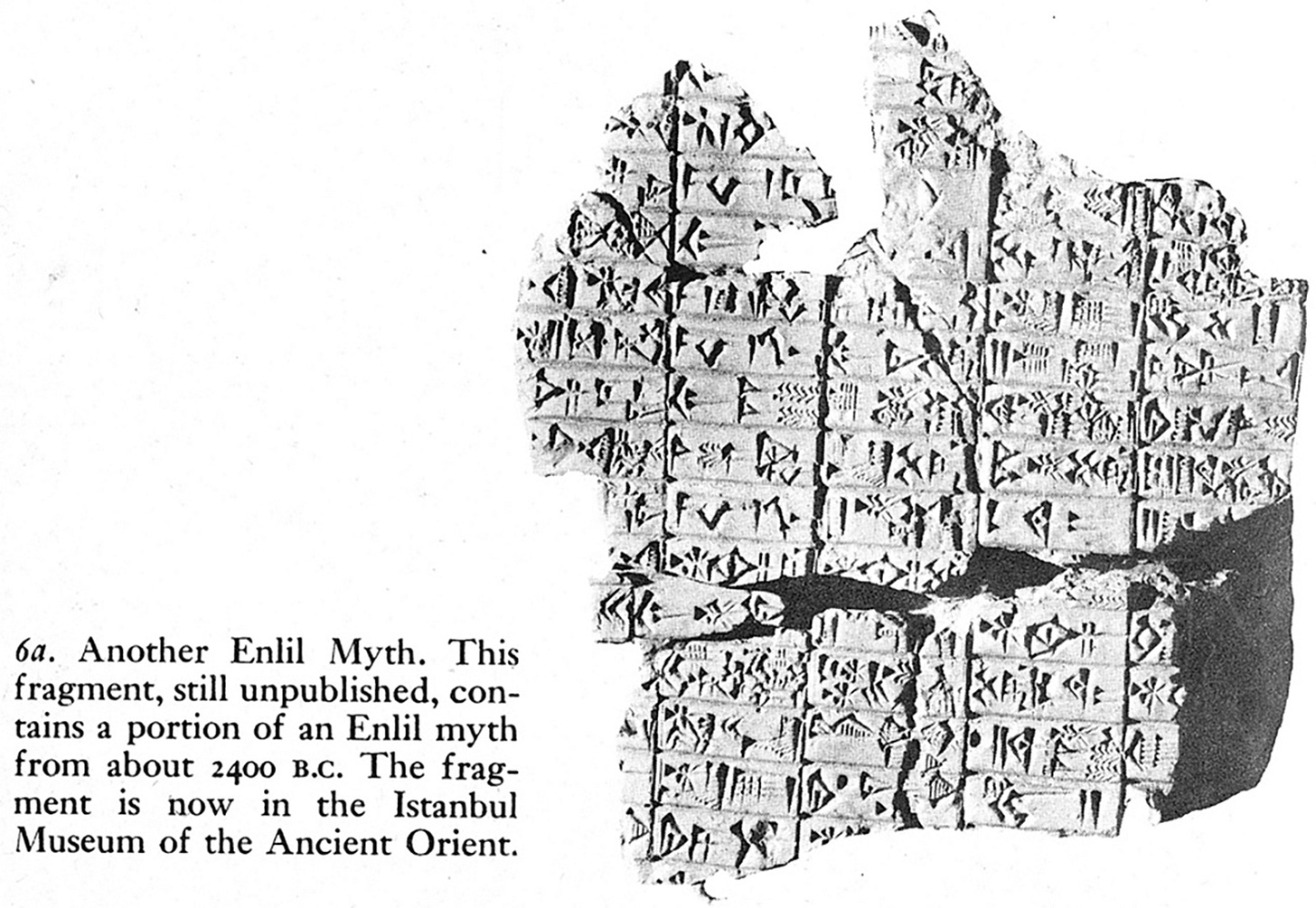

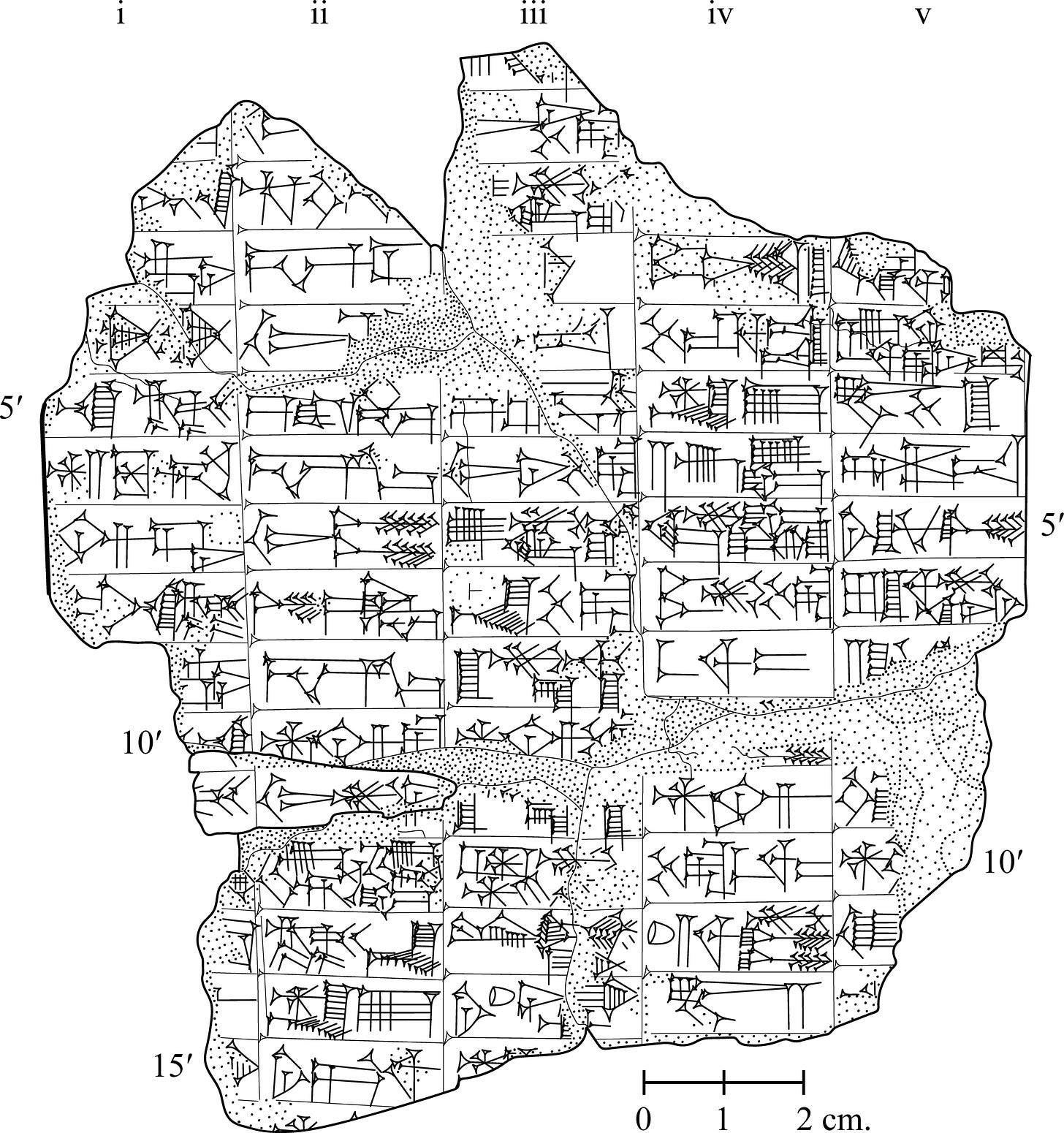

In a modest sliver of clay, broken and partially erased by time, a story emerges from the city of Nippur in ancient Sumer that offers a window into the mythological imagination of one of the world’s earliest civilizations. The tablet, catalogued as Ni 12501 and dating to roughly 2400 BCE, carries a tale involving divine assemblies, netherworld imprisonments, agricultural abundance, and a fox playing the unlikely hero.

Although its surface is damaged and its lines fractured, the surviving portions of Ni 12501 tell a tale with enough clarity to suggest both its cultural importance and its narrative richness. Published and analyzed in detail for the first time by Assyriologist Dr. Jana Matuszak in the journal Iraq1, the tablet offers rare insight into local myth-making in early Sumerian society.

“Enlil is the acting head of the Sumerian pantheon and is often referred to as king of the gods,” writes Matuszak. “In what is preserved of Ni 12501, his leading role can be seen in the fact that he has the authority to convene the divine assembly.”

At the heart of the story lies Ishkur, the Sumerian storm god, who is imprisoned in the kur—a term that can denote both the underworld and a more ambiguous cosmic frontier. With Ishkur held captive, agricultural abundance vanishes. His multicolored cattle and fish-filled rivers become distant memories. Children are born but are swept into the netherworld. In his absence, the world wilts.

This decline prompts Enlil, Ishkur’s father and the supreme god of Nippur, to call a divine assembly. Yet none of the gods will volunteer to venture into the kur to retrieve Ishkur. Only the fox steps forward.

“The Nippur fragment Ni 12501 is the only narrative in which Ishkur plays a leading role,” Matuszak explains. “In other texts, he is relatively marginal.”

The fox enters the kur by feigning acceptance of hospitality. Offered food and drink, he hides them rather than consumes them. The strategy seems to trick the chthonic forces, and from this point the narrative cuts off, leaving open the question of whether Ishkur is ultimately freed.

A Myth Rooted in Sumerian Ecology and Theology

The myth comes from a time when southern Mesopotamia’s urban centers—such as Nippur and neighboring Adab—shared a rich yet regionally inflected religious world. Each city had its patron deity, temple economy, and oral mythologies. Nippur’s political autonomy coexisted with a broader network of shared writing systems, beliefs, and practices.

Matuszak places Ni 12501 squarely within this context:

“Each city-state had one patron deity… In the case of Nippur, this was Enlil. But cities had various temples dedicated to other deities as well… They generally shared similar political and administrative practices, a language, a writing system, and a belief system, with local differences.”

In a place where irrigation—not rainfall—was the key to survival, the storm god Ishkur held a peculiar status. Unlike his northern Semitic counterparts, whose rains fertilized fields, Ishkur represented seasonal unpredictability in a landscape where canals, not clouds, brought water to the crops. Still, his mythic presence was tied to fertility, abundance, and perhaps the dread of seasonal absence.

The myth’s opening lines describe an idyllic landscape full of Ishkur’s bounty: vibrant rivers, thriving livestock, and fruiting fields. When Ishkur disappears into the kur, drought and death descend. The motif of the captive deity whose return heralds renewal recurs in Mesopotamian literature, echoing across later myths of Dumuzi and Inanna, or Tammuz and Ishtar.

The Fox as Trickster, Before the Trickster Became Archetype

One of the most intriguing aspects of Ni 12501 is the role of the fox. In what may be the earliest recorded instance of the animal’s cunning in myth, the fox steps into a space vacated by the gods and accomplishes what they would not. The episode predates Aesop and Reynard, and suggests that even in the third millennium BCE, Mesopotamians were imagining the world not only through divine intervention but through the craft and guile of animals.

“This is the earliest attestation of the motif of the cunning fox,” Matuszak writes. “The helpless gods are saved by an unlikely hero who comes to accomplish what the gods cannot.”

What is not preserved is just as haunting as what is. Did the fox succeed? Was Ishkur restored to the heavens? Or did the netherworld win this round? The broken tablet leaves the arc incomplete, inviting speculation and underscoring the fragmentary nature of what survives from Sumerian religion.

A Story Worth the Wait

Though excavated in the 19th century, Ni 12501 remained unpublished for over a century, not least because of its damaged condition. It appeared briefly and unattributed on the dust jacket of a book by Samuel Noah Kramer in 1956, but its museum number was only published later. It is a minor miracle that it was not lost to scholarship altogether.

The tablet’s belated publication reminds us how much remains to be gleaned from even well-known archaeological collections. Motifs from the story—divine assemblies, trickster animals, descent to the netherworld—surface again and again in later Mesopotamian texts, suggesting that Ni 12501, though locally rooted in Nippurite tradition, echoed further than the city that created it.

“Despite their political autonomy,” Matuszak notes, “the city states generally shared similar… belief systems… For Ni 12501, this means that it likely presents a Nippurite tradition, but… there’s no reason to believe that people would have contested it in any way.”

As the Sumerian pantheon evolved and reshaped itself over the centuries, the characters and themes of this obscure myth were never far from view. The fox reappears. The captive god returns. The kur remains a place of mystery and dread. And Ishkur, seldom the star of the story, here receives his moment in the mythological sun.

Additional Related Research

Wilcke, C. (1998). Early Dynastic and Sargonic Literature. In J.M. Sasson (Ed.), Civilizations of the Ancient Near East, pp. 2279–2291. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

[Classic overview of Sumerian literary traditions.]George, A.R. (2003). The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic: Introduction, Critical Edition and Cuneiform Texts. Oxford University Press.

[Traces themes of divine descent and return across Mesopotamian texts.]Black, J.A., Green, A., & Postgate, J.N. (2004). Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Illustrated Dictionary. University of Texas Press.

[Key resource for decoding Sumerian religious symbols.]Bottéro, J. (2001). Religion in Ancient Mesopotamia. University of Chicago Press.

https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226067186.001.0001

[In-depth discussion of Mesopotamian religious cosmology.]Alster, B. (2005). Wisdom of Ancient Sumer. CDL Press.

[Explores literary motifs, including animal tricksters and divine counsel.]

Matuszak, J. (2024). Of captive storm gods and cunning foxes: New insights into early Sumerian mythology, with an edition of Ni 12501. Iraq, 86, 79–108. https://doi.org/10.1017/irq.2024.19