Did Getting Tipsy Help Build Civilization?

The rise of complex societies is often credited to agriculture, organized religion, and advances in warfare. But what if some of that progress fermented at the bottom of a communal clay jar?

A recent cross-cultural analysis published in Humanities & Social Sciences Communications1 examines the idea that traditional fermented alcoholic beverages—like beer and wine—may have played a supporting role in the evolution of large-scale, stratified societies. The study’s findings are modest in their conclusions but intriguing in their implications: alcohol, long a tool of social cohesion and elite spectacle, may have helped humans scale up from kin-based groups to hierarchical civilizations.

“Intoxication reduces cognitive control, which may open people up to new forms of bonding and cooperation,” the authors note, referencing a body of research that links alcohol consumption with creative problem-solving and prosocial behavior.

This so-called "drunk hypothesis," popularized by philosopher Edward Slingerland, proposes that humans evolved not despite our love of booze, but partly because of it. Drinking together helps bind communities, builds trust among strangers, and—especially in early societies—was often overseen and distributed by emerging elites.

Testing the Drunk Hypothesis

Anthropologists Václav Hrnčíř, Angela Chira, and Russell Gray of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology set out to test the hypothesis using one of the largest cross-cultural databases available: the Standard Cross-Cultural Sample, or SCCS. It includes 186 largely non-industrial societies described before heavy colonial influence altered their cultural landscapes.

The researchers created a new dataset that tracked whether each society brewed or fermented its own traditional alcoholic beverages—meads, wines, beers—but excluded high-alcohol distilled liquors, which tend to have more disruptive social effects.

They then measured the political complexity of these societies using a scale based on the number of administrative levels present, ranging from acephalous groups with no formal leadership to stratified polities with centralized authority.

Across all models tested, a pattern emerged:

“There is a consistent, positive relationship between the presence of indigenous fermented drinks and higher levels of political complexity,” said Hrnčíř, though he cautioned that the effect size was modest and likely secondary to more powerful forces like agriculture.

Drinking and Thinking Together

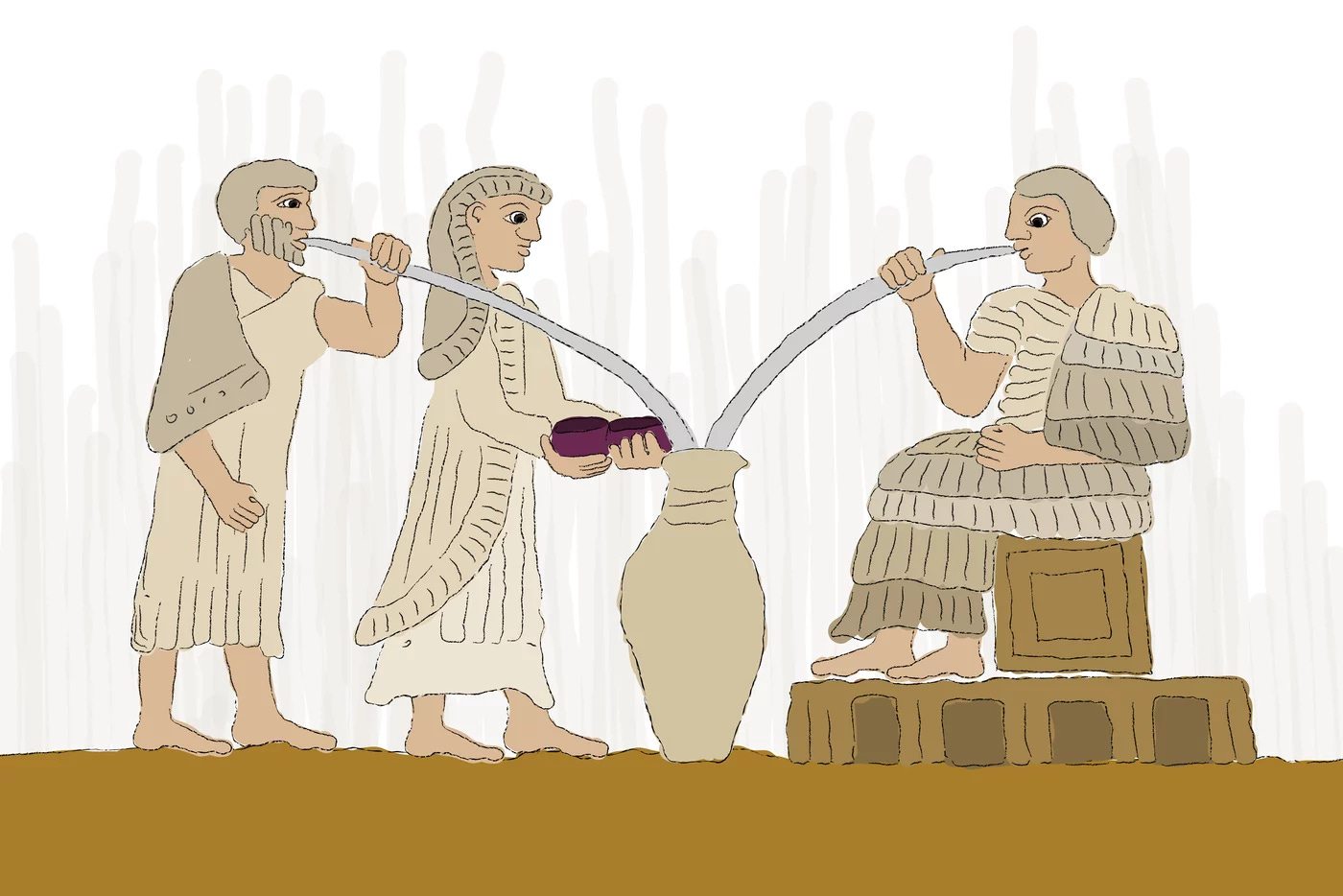

Throughout the Holocene, alcohol has flowed through the rituals and politics of civilization. In Mesopotamia, beer was an offering to the gods and a form of currency. In Mesoamerica and the Andes, fermented maize drinks were central to public feasts and political negotiation. Among early Indo-European societies, warriors pledged loyalty during inebriated banquets.

These traditions weren't just about getting drunk. Communal drinking shaped the social fabric.

“Alcohol is a tool of affiliation,” noted the authors. “It helps establish obligations, maintain hierarchies, and foster cooperation—all essential ingredients in complex societies.”

But was alcohol a cause or a consequence of social complexity?

To parse this, the researchers used causal inference modeling, controlling for confounding factors such as environmental productivity and the presence of agriculture. When agriculture was taken into account, the effect of alcohol weakened—but it remained statistically relevant.

Modeling also showed that societies with fermented beverages were more likely to shift from egalitarian structures toward hierarchical forms. Alcohol did not birth the state, but it may have been one of many scaffolds that held early social institutions together.

Not All Drinks Are Equal

Interestingly, traditional alcohol production was unevenly distributed. It was common in much of Eurasia, Africa, and South America, but rare in pre-contact North America and Oceania. This wasn’t due to lack of ingredients—many wild plants can be fermented—but may reflect different ecological constraints or cultural preferences.

The study also distinguished between traditional fermented drinks and distilled liquors. The latter, with much higher alcohol content, are more recent and often tied to social disruption—especially when introduced rapidly by colonial powers into societies without long-standing drinking norms.

“The social effects of alcohol depend on context: how it’s made, shared, and embedded in cultural practices,” the researchers observed.

In pre-industrial settings, drinking was typically communal, celebratory, and ritualized. Solitary or habitual drinking—the kind more common in modern contexts—was rare.

The Bigger Picture

While this study supports the idea that alcohol had a positive (if minor) association with political complexity, it also underscores the caution needed in interpreting causality. Agriculture remains the clearest driver of societal complexity, providing surplus food that enabled population growth and institutional development.

Still, alcohol may have served as a social lubricant at critical junctures.

Whether to ease the friction of hierarchical living, seal alliances, mobilize collective labor, or commemorate victory, fermented beverages helped bring people together—and keep them together.

And that, in the long arc of human history, may have mattered.

Related Research:

Guerra-Doce, E. (2015). The Origins of Inebriation Rituals in Prehistoric Europe. World Archaeology, 47(1), 78–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.2015.991408

Explores archaeological evidence for alcohol use in prehistoric European rituals.

Dietler, M. (2006). Alcohol: Anthropological/Archaeological Perspectives. Annual Review of Anthropology, 35, 229–249. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.35.081705.123120

A foundational synthesis of alcohol’s social and political functions in antiquity.

Slingerland, E. (2021). Drunk: How We Sipped, Danced, and Stumbled Our Way to Civilization. Little, Brown Spark.

A book-length case for the role of alcohol in shaping cultural evolution.

Jennings, J. et al. (2005). "Drinking Beer in a Blissful Mood": Alcohol Production, Operational Sequences, and Feasting in the Ancient World. Current Anthropology, 46(2), 275–303. https://doi.org/10.1086/427115

Highlights the role of alcohol in early feasting rituals and statecraft.

Hrnčíř, V., Chira, A. M., & Gray, R. D. (2025). Did alcohol facilitate the evolution of complex societies? Humanities & Social Sciences Communications, 12(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05503-6