The Call That Traveled Through Time

If you stand today in the pre-coastal valleys of Catalonia, it takes little imagination to hear how sound might carry across the ridges and river plains. Six thousand years ago, those same landscapes were alive with the routines of early farmers, miners, and craftspeople. What we rarely consider is that these communities were not only makers of pottery, stone tools, and ornaments. They were also makers of sound.

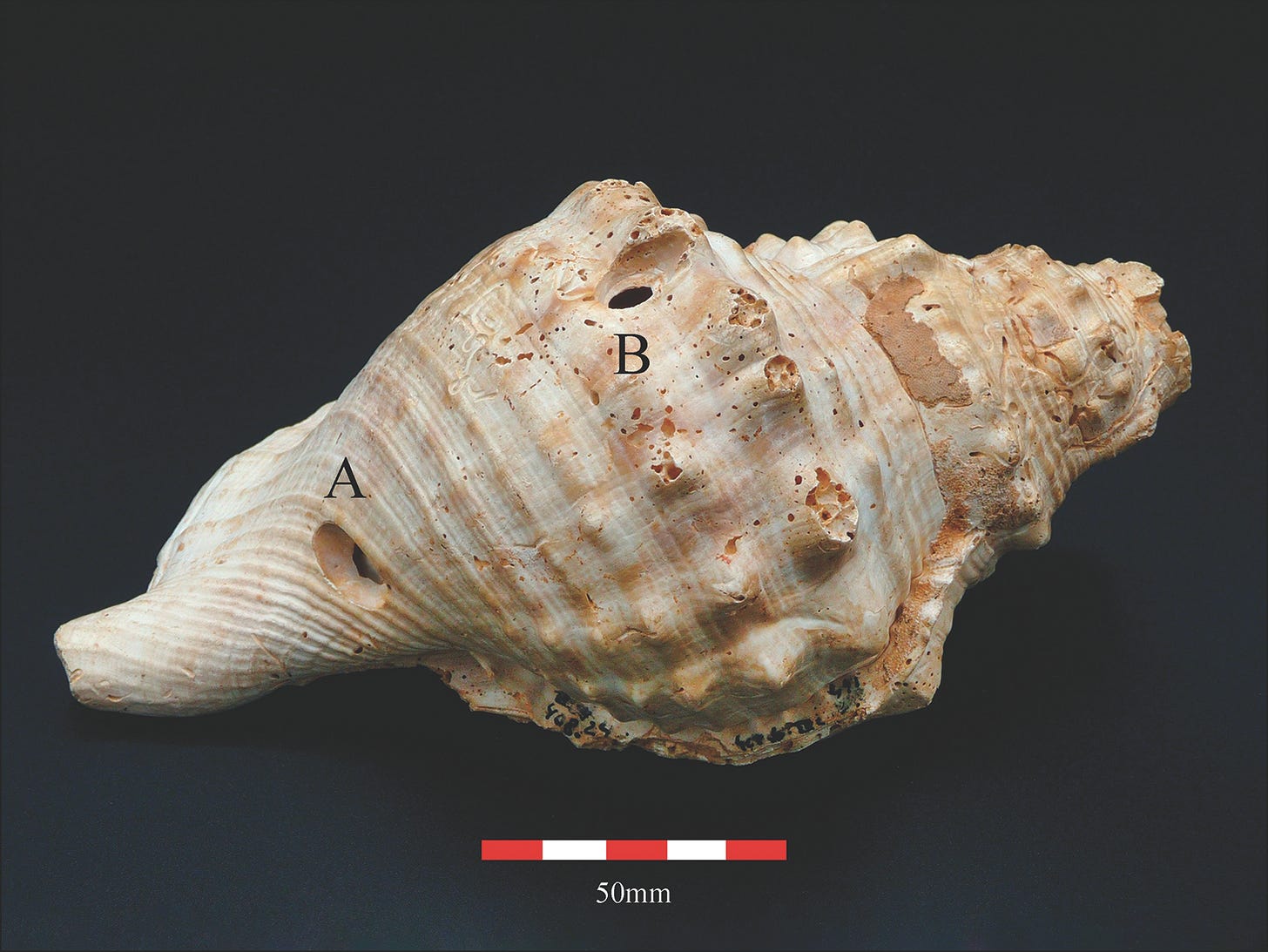

A new study of Neolithic shell trumpets from Catalonia, published in Antiquity,1 places acoustics at the center of prehistoric communication. By playing original artifacts that still function as instruments, researchers have shown that these Charonia lampas shells were not decorative curiosities. They were powerful tools designed to pierce distance, coordinate labor, and, at times, create something like music.

The implications ripple outward. Sound, it turns out, may have been as critical to Neolithic social life as any blade or bead.

“The shells expand the sensory map of the Neolithic,” says Dr. Helena Marquès, an archaeologist at the University of Barcelona. “They show that communication in these communities did not rely solely on paths and sightlines. Their world was also shaped by intentional sound.”

Miquel López-Garcia playing one of the shell trumpets. Credit: The authors

Where the Shells Were Found

A Cluster That Was Never Coincidental

Twelve shell trumpets have been recovered from early agricultural settlements, burial contexts, and even mining galleries across a narrow region stretching from the Llobregat River basin to the Penedès depression. Their dates fall between the late fifth and early fourth millennia BC, a period of expanding farming and intensifying social networks.

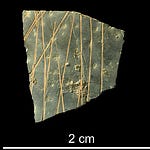

These sites are not random. Many were densely populated, strategically placed along river corridors, or positioned near the Neolithic variscite mines of Gavà, where green stone was extracted for prized ornaments that traveled widely across Europe.

Even before their acoustic analysis, the placement of the shells hinted at shared practices. Instruments found in mine backfill, storage pits, and domestic areas suggest their significance in daily life as much as in ritual.

“The concentration of instruments over such a compact region suggests coordinated behaviors,” argues Dr. Samuel Pardo, a specialist in prehistoric communication networks. “These were not isolated experiments in sound. They reflect a shared social technology.”