Life Where the Air Thins

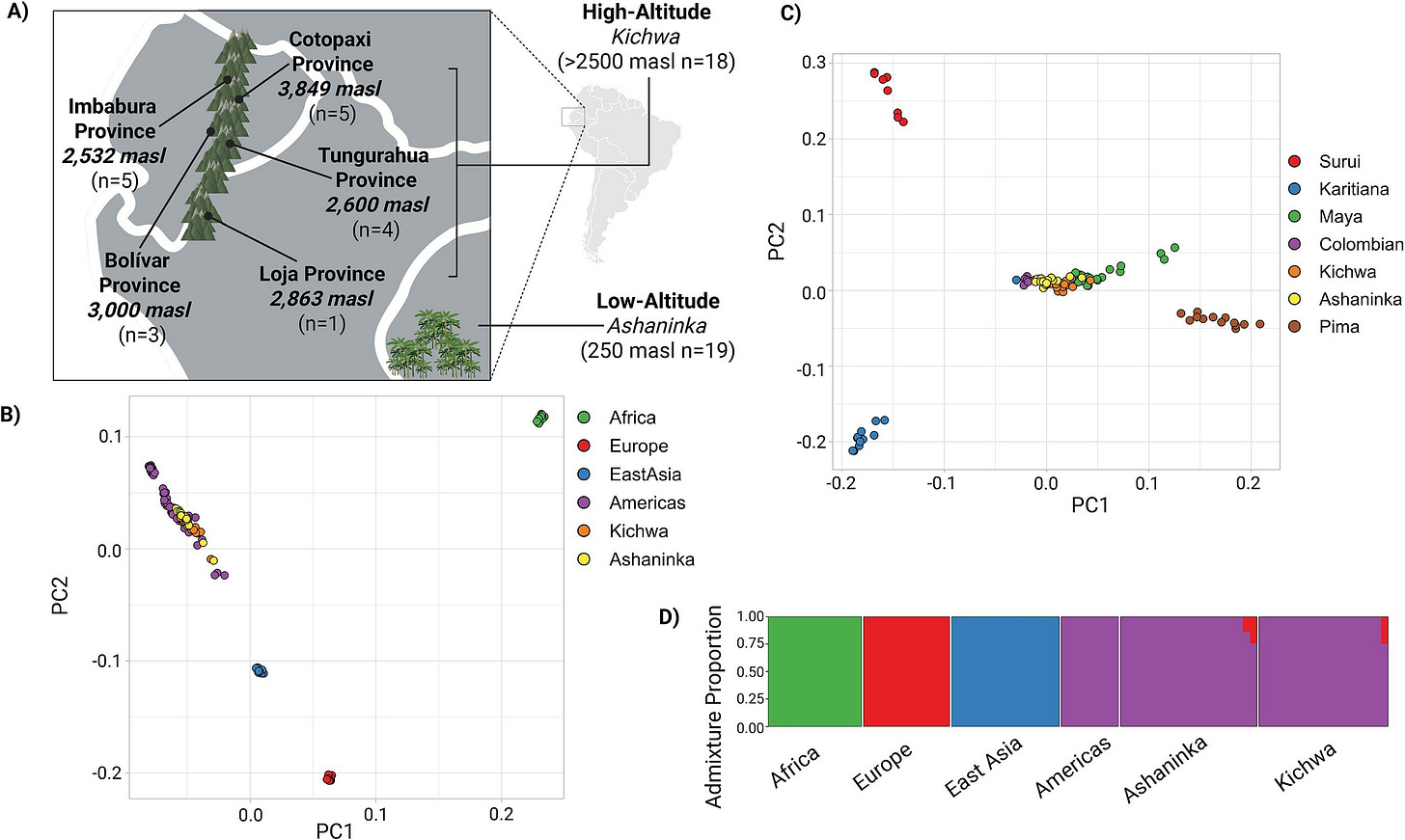

High-altitude environments have a way of rearranging human biology. Pulse quickens, lungs strain, blood thickens. For people who grow up where the atmosphere refuses to cooperate, the challenge is constant. Yet different populations have responded in remarkably different ways. In Tibet, for instance, a genetic variant in the EPAS1 gene famously helps residents thrive at more than 4,000 meters.

But across the Andes, where Indigenous communities have lived at high elevation for nearly 10,000 years, genetic explanations have never fully added up. The expected markers simply are not there. It has long been a puzzle: how have Andean highlanders endured such thin air without a clear genomic signature of adaptation?

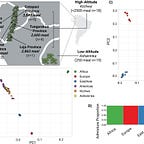

A new study1 led by researchers at Emory University offers a compelling possibility. Instead of looking for changes in the DNA code itself, the team scanned entire methylomes, the chemical accents that influence how genes behave. Their findings suggest that the Andean response to altitude may be written not in letters but in punctuation marks layered on top of the genome.

“Epigenetic shifts reveal a dimension of adaptation that leaves minimal trace in the genetic sequence yet has profound physiological effects,” says Dr. Nora Valdez, a bioanthropologist at the University of La Plata. “This study provides rare molecular evidence for that idea.”