A Burial, a Pit, and a Puzzle

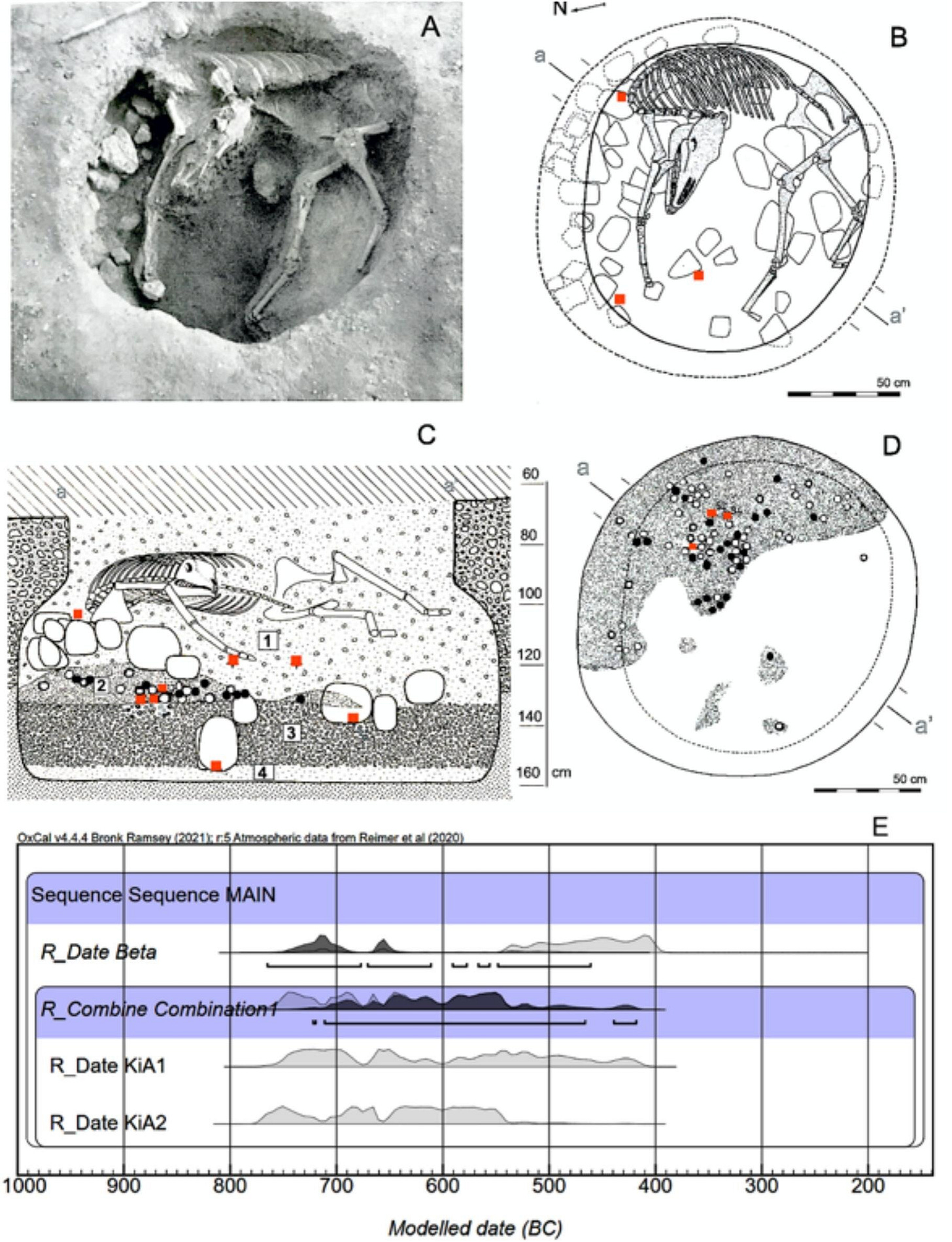

Archaeology often advances not through glittering artifacts but through quiet puzzles that refuse to go away. One of these puzzles emerged from a pit in the Penedès region of northeastern Spain, where excavators in 1986 documented the charred remains of a woman interred with an equally unexpected companion: the skeleton of an equid whose identity would remain uncertain for decades.

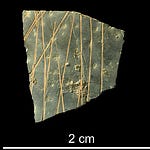

The bones waited in museum storage until researchers from the University of Barcelona and collaborating institutions returned to them with new tools and broader questions. Radiocarbon dating and genetic sequencing ultimately delivered a surprise.1 The animal was a mule, and not just any mule but the earliest known specimen in the western Mediterranean and continental Europe, dated to the 8th to 6th centuries BCE. Its presence shifts the timeline of hybrid equid breeding far earlier than once assumed.

“The animal signals an exchange network that was operating on multiple levels, from livestock to ideas about animal management,” says Dr. Isabel Corvacho, an archaeozoologist at the University of Seville. “Its biography does not belong to the local landscape alone.”