In a well near the modern city of Faenza, archaeologists stumbled across a set of infant remains so degraded that little more than dental crowns and bone fragments were salvageable. No burial shroud, no grave goods. Just a few ceramic sherds and a shallow pit—perhaps once a well—marking the child’s final place of rest in Italy's Copper Age, roughly five millennia ago.

What followed was not a typical excavation report1. Instead, it became an experiment in forensic patience, bringing together advanced techniques in dental histology, proteomics, and ancient DNA analysis to resurrect a lost biography from a few grams of mineralized tissue.

Age from Enamel: Counting Days in Tooth Growth

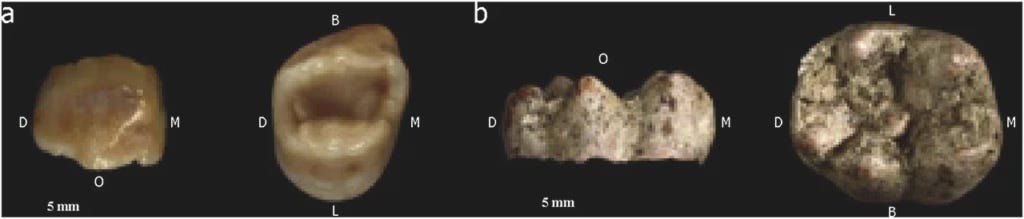

The team began with two molars: a deciduous upper first molar and a permanent lower molar. These teeth, though tiny, served as calendars etched in enamel. Using polarized light microscopy, scientists traced incremental growth lines, daily secretion rates, and even a neonatal line—a distinct marker separating pre- and post-birth enamel. The results were both precise and personal.

"Based on the histological record, the child died around 17 months old, give or take a few weeks," said the researchers.

There were no signs of enamel hypoplasia or accentuated stress lines. Whatever led to this child's early death, it likely wasn’t prolonged malnutrition or systemic illness.

DNA from Dust: A Maternal Lineage Reappears

Next came the genetic work. A fragment of compact bone, less than a centimeter in length, held just enough viable DNA to recover the mitochondrial genome. The sequencing pointed to a rare lineage: haplogroup V+@72.

This particular maternal lineage is scarcely found in modern populations, aside from trace levels among the Saami of northern Scandinavia and isolated groups in the western Mediterranean. The only other ancient case comes from a Copper Age site in Sardinia. The connection, while speculative, raises questions about prehistoric movement across the Italian peninsula and beyond.

"The infant’s mitogenome is a needle in the haystack of European prehistory," one team member noted. *"It hints at population complexity we’re just beginning to map."

False Starts: What Collagen and Strontium Couldn't Say

Radiocarbon dating was attempted but failed. The collagen in the bones had decayed past usability. Similarly, trace element analysis of enamel, which can sometimes reveal nursing and weaning patterns, was rendered unreliable by post-burial contamination. Diagenetic signatures, particularly from uranium and manganese, masked the biogenic signals.

Still, the failure revealed something: just how much ancient chemistry can interfere with modern archaeology. And how even that interference carries meaning.

Sex Through Peptides: When Bone Won't Talk

When DNA is too damaged, proteins often remain. Proteomic analysis of tooth enamel identified both AMELX and AMELY peptides, which correspond to amelogenin proteins on the X and Y chromosomes. The presence of both confirmed that the infant was male.

This sex estimation, confirmed independently by both proteomic and genetic methods, strengthened the profile of this otherwise anonymous child.

Final Thoughts: What a Tooth Can Hold

This infant, buried in an abandoned well, may never have been commemorated with ritual or memory. Yet his molars recorded a short life lived without apparent trauma, in a time before written history but not before the human experience.

What the study makes clear is this: even in cases where skeletal preservation borders on failure, there are ways to listen. A single molar can reveal a developmental story measured in microns and days. A fragment of bone can whisper of long-lost lineages.

Related Studies

Fernandes, D. M., et al. (2018). "The spread of steppe and Iranian-related ancestry in the islands of the western Mediterranean." Nature Ecology & Evolution. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-018-0510-7

Olalde, I., et al. (2018). "The Beaker phenomenon and the genomic transformation of northwest Europe." Nature, 555, 190–196. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature25738

Villalba-Mouco, V., et al. (2021). "Survival of Late Pleistocene hunter-gatherer ancestry in the Iberian Peninsula." Current Biology, 31(6), 1248-1257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2020.11.036

Tambets, K., et al. (2004). "The western and eastern roots of the Saami: analyses of mitochondrial DNA and Y chromosome polymorphisms." European Journal of Human Genetics, 12(7), 494-504. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201161

Pinhasi, R., et al. (2015). "Optimal ancient DNA yields from the inner ear part of the human petrous bone." PLoS ONE, 10(6): e0129102. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0129102

Higgins, O. A., Fontani, F., Lugli, F., Silvestrini, S., Vazzana, A., Latorre, A., Sericola, M., Cipriani, A., Quarta, G., Calcagnile, L., Bondioli, L., Nava, A., Cilli, E., Luiselli, D., & Benazzi, S. (2025). Reconstructing life history and ancestry from poorly preserved skeletal remains: A bioanthropological study of a Copper Age infant from Faenza (RA, Italy). Journal of Archaeological Science, 180(106291), 106291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2025.106291