More than 3,000 years ago, long before Rome rose or Athens dreamed of democracy, bronze was already reshaping the ancient world. Weapons, tools, and ornaments forged from this copper-and-tin alloy were transforming everything from warfare to daily labor. But while copper is relatively easy to find, tin is elusive. It doesn’t litter the ancient Mediterranean the way obsidian or copper does. And yet, by 1300 BCE, civilizations across the eastern Mediterranean were awash in bronze.

That paradox has haunted archaeology for decades. Known as the “tin problem,” it hinges on a simple question: Where did the Bronze Age world get all its tin?

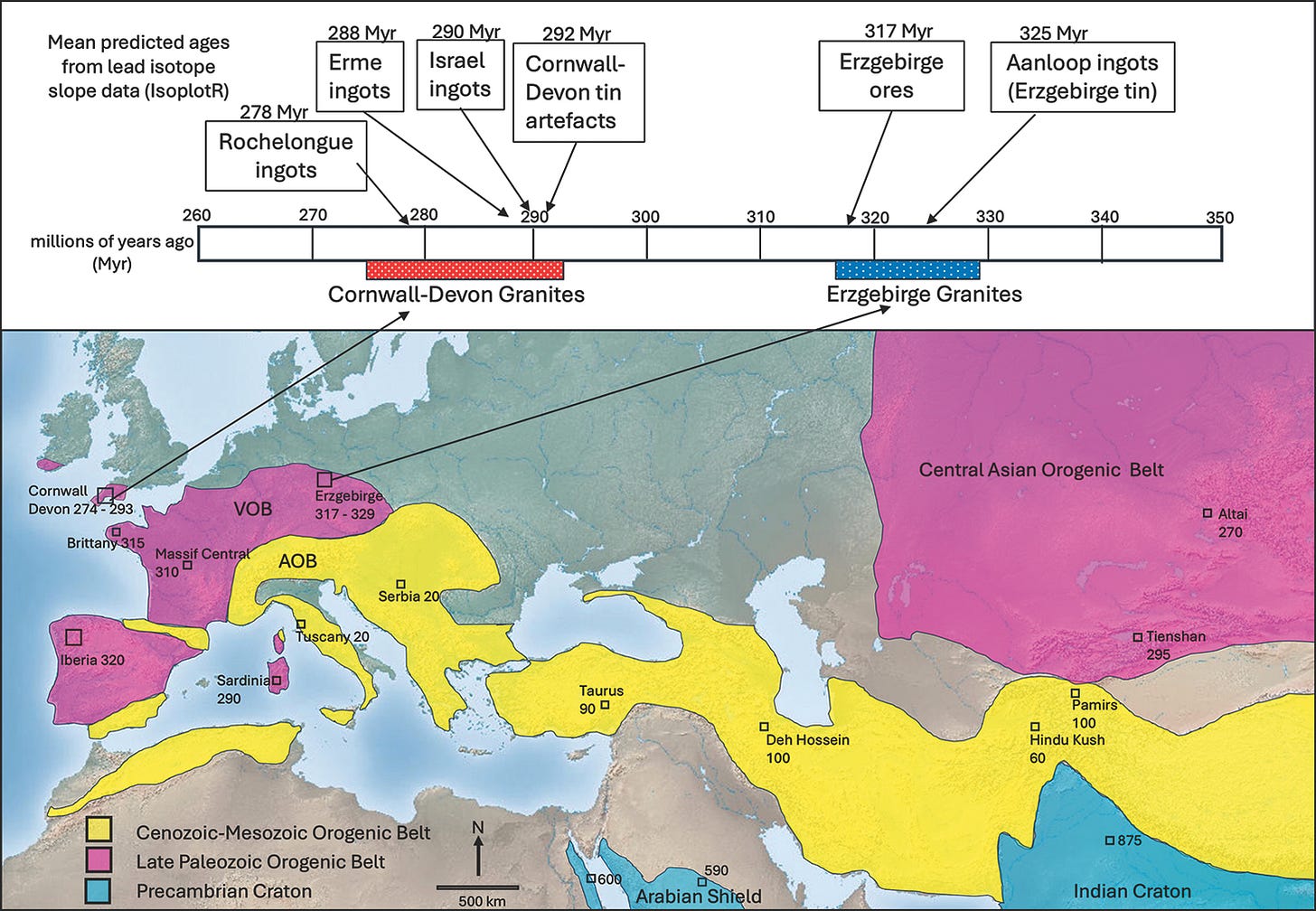

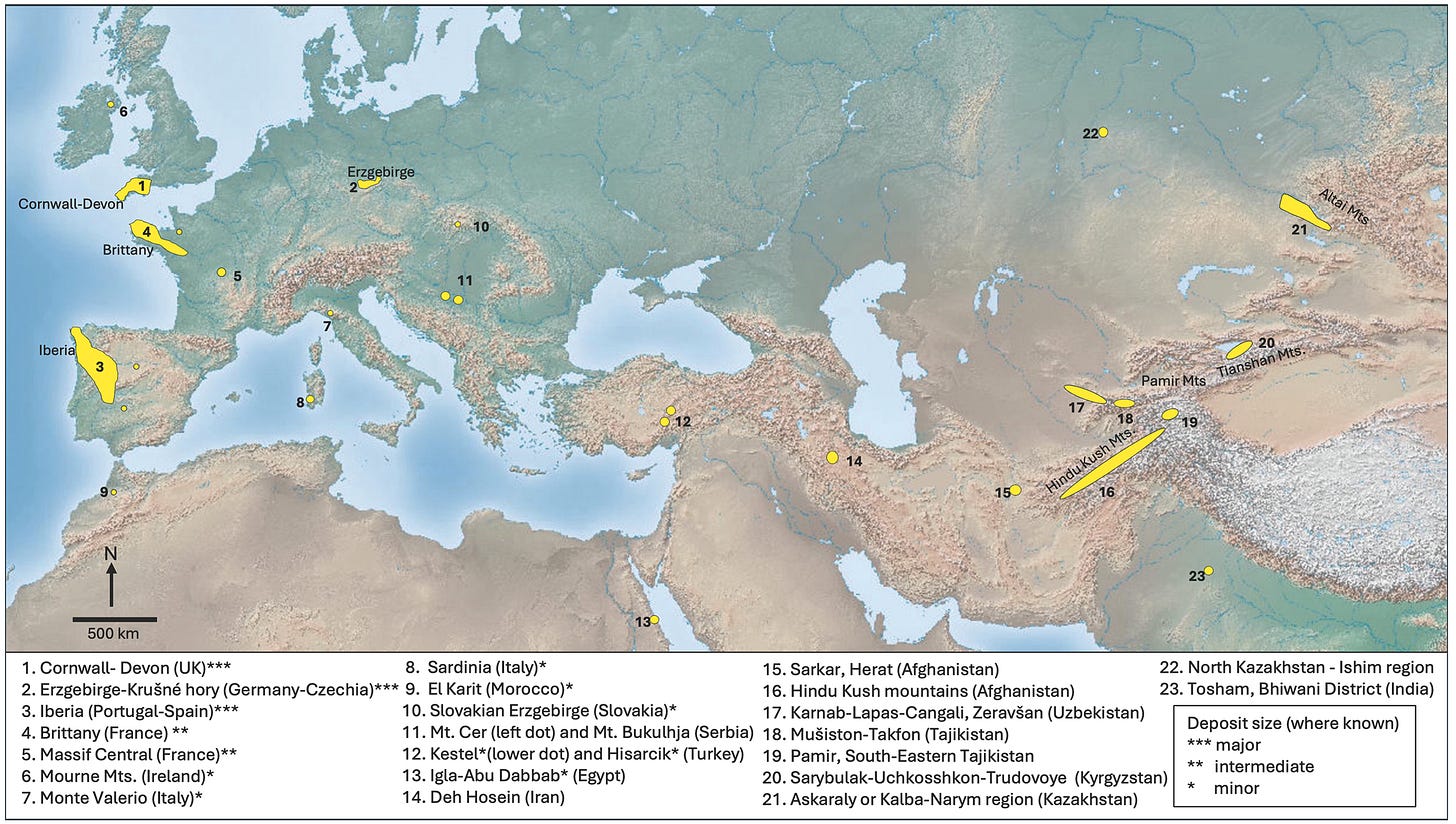

Now, thanks to a multi-year geochemical study1 led by a British research team, there’s a compelling answer—and it reaches farther northwest than many suspected. New trace element and isotope data point to the windswept cliffs of Cornwall and Devon, suggesting that southwestern Britain was supplying tin to the Mediterranean world long before most scholars thought such trade was possible.

“This is the first commodity to be exported across the entire continent in British history,” said Dr. Benjamin Roberts, associate professor of archaeology at Durham University. “It requires an entirely new perspective on what Bronze Age miners and merchants were able to achieve.”

From Wind-Carved Cliffs to Levantine Ports

The researchers conducted compositional analysis of tin ingots recovered from Bronze Age shipwrecks, including three that sank off the Israeli coast. Using lead isotope ratios and tin trace elements, they compared these artifacts with ores from known tin sources in Europe—including Cornwall’s massive deposits. The chemical fingerprint matched.

Not only were the ingots compatible with British sources, but the scale and consistency of their presence suggested something even more striking: organized, sustained trade across thousands of kilometers, long before written records or urban centers existed in Britain.

The route, pieced together like shards of a broken amphora, ran from Cornwall through the rivers of France, past Sardinia, Cyprus, and onward to the Levant. This was not an accidental trickle. It was a system.

“A whole chain of interconnected communities was involved,” said Roberts.

“From miners in the British Isles to sailors in the Aegean and metallurgists in the Levant.”

For archaeologists who have long viewed Bronze Age Britain as isolated or peripheral, the findings challenge deep-seated assumptions. Cornish tin, it seems, didn’t just help forge weapons and tools. It stitched distant communities together.

A Mining Culture Without Cities

What makes the story more astonishing is who was doing the mining. By the standards of the ancient Mediterranean, Bronze Age Britain was rustic. No palaces. No temples. No writing. Its inhabitants lived in scattered farming settlements, leaving behind little more than postholes, pottery, and the occasional hoard.

And yet these people, often imagined as insular and self-sufficient, appear to have contributed the essential ingredient for a metallurgical revolution that would ripple across Egypt, Anatolia, and the Levant.

Dr. Alan Williams, a geologist-turned-archaeologist and honorary fellow at Durham University, has spent five decades tracing the origins of Cornish tin. He first dreamt of this connection as a student in one of the last working tin mines in the region.

“We believe Cornish tin was the richest, the most easily accessible, and the main source,” Williams explained.

The evidence includes not just the ingots, but also geological samples, traceable through advanced spectroscopy and mass spectrometry. One tin ingot found in the Uluburun shipwreck off Turkey—long believed to be among the oldest shipwrecks in the world—may also have come from Cornwall.

Bronze Age Globalization

Historians have long spoken of the Late Bronze Age as a proto-globalized era, characterized by diplomatic letters between pharaohs and kings, trade in luxury goods, and widespread cultural exchange. But these networks have typically been viewed as Mediterranean-bound.

This new evidence suggests that the edges of the known world—like windswept Cornwall—were far more connected than previously imagined.

“It radically transforms our understanding of Bronze Age Britain’s place in the wider world,” Roberts said.

Such trade required not only knowledge of distant lands but also the logistical infrastructure to move cargo, safeguard routes, and negotiate exchanges. That this was accomplished without writing or centralized state structures only deepens the mystery—and admiration—for these early traders.

What’s Next: A Dig at St Michael’s Mount

Roberts and Williams are now turning their attention to a site with almost mythical status in Cornish lore: St Michael’s Mount. The tidal island, now crowned by a medieval abbey, may once have served as a Bronze Age tin smelting center and maritime hub.

Excavations planned for the coming year will probe for evidence of Bronze Age activity—metallurgical waste, harbor installations, or perhaps even dwellings that once housed the people behind this transcontinental exchange.

Recasting the Bronze Age Narrative

Cornish tin isn’t just a mineral. It’s a clue. A clue that suggests the periphery was never as peripheral as it seemed.

From the highlands of Anatolia to the shipwrecks of the Levant, bronze shaped the tools of farmers, the blades of warriors, and the adornments of the elite. And behind it all, at least in part, were miners in a distant, foggy land at the western edge of Europe.

Related Research

Berger, D., et al. (2019). “Tin Isotopes and the Sources of Tin in the Bronze Age.” Nature Communications, 10, 5000. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-12925-0

Haubner, R., Lux, B., & Mitterbauer, E. (2020). “Metal Flow in Bronze Age Trade: Evidence from Chemical Composition.” Archaeometry, 62(4), 783–800. https://doi.org/10.1111/arcm.12543

Cierny, J., & Weisgerber, G. (2003). “The Early Bronze Age Tin Trade in Central and Eastern Europe.” Der Anschnitt, 16(Suppl), 59–74.

Williams, R. A., Montesanto, M., Badreshany, K., Berger, D., Jones, A. M., Aragón, E., Brügmann, G., Ponting, M., & Roberts, B. W. (2025). From Land’s End to the Levant: Did Britain’s tin sources transform the Bronze Age in Europe and the Mediterranean? Antiquity, 0(0), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2025.41