Linguists have long mapped the world's languages as grand family trees. They draw neat branches to show how Latin gave rise to French, Spanish, and Italian, or how a single Proto-Germanic root sprouted the distinct forms of English, German, and Swedish. This view, of languages passed vertically from one generation to the next, is a powerful way to visualize history. It is a story of inheritance, of ancestral words and grammars persisting through time, modified only slightly by each passing century. It is a clean and satisfying picture. But it is also incomplete.

The reality of language is far messier. It is a story not just of descent but of borrowing. Throughout human history, populations have met, interacted, and mingled, and with them, their languages have done the same. Words leap from one language to another; new sounds are adopted; grammatical structures shift. This process is known as horizontal transfer, and it is a fundamental force in how languages evolve. Yet, for all its importance, it has remained a puzzle, a vast historical landscape shrouded in mist. How can we possibly measure the effect of contact when so much of human history remains unrecorded?

A recent study published in Science Advances1 offers a new way to pierce through that mist. By turning to a different kind of historical record—the human genome—researchers have found a way to quantify the effects of population contact on language at a global scale. The analysis of this data suggests that the story of linguistic evolution is not just one of persistence and change, but of surprising and consistent patterns that transcend time, place, and the immense social complexities of human interaction.

The Ghost of Encounters Past

For centuries, the only way to study linguistic borrowing was through the circumstantial clues left behind in the historical record. A linguist might notice a pattern in the grammars of two unrelated languages in a certain region and infer that they must have once been in contact. The evidence for such contact, however, was often pieced together from fragmented historical accounts or geographical proximity, leaving large gaps in our understanding. This made it nearly impossible to draw global conclusions about how contact shapes language. The historical evidence was largely circumstantial, and a systematic, cross-cultural study of borrowing rates seemed out of reach.

The team behind the new study, led by Anna Graff and Chiara Barbieri, sought a solution in the field of population genetics. Their premise was straightforward: if a population's genes can tell us about past mixing events, why couldn't they also tell us about the cultural exchange that likely took place at the same time? They proposed that genetic admixture—the presence of genetic material from two previously distinct ancestral populations in a single modern population—could serve as a reliable, independent proxy for population contact.

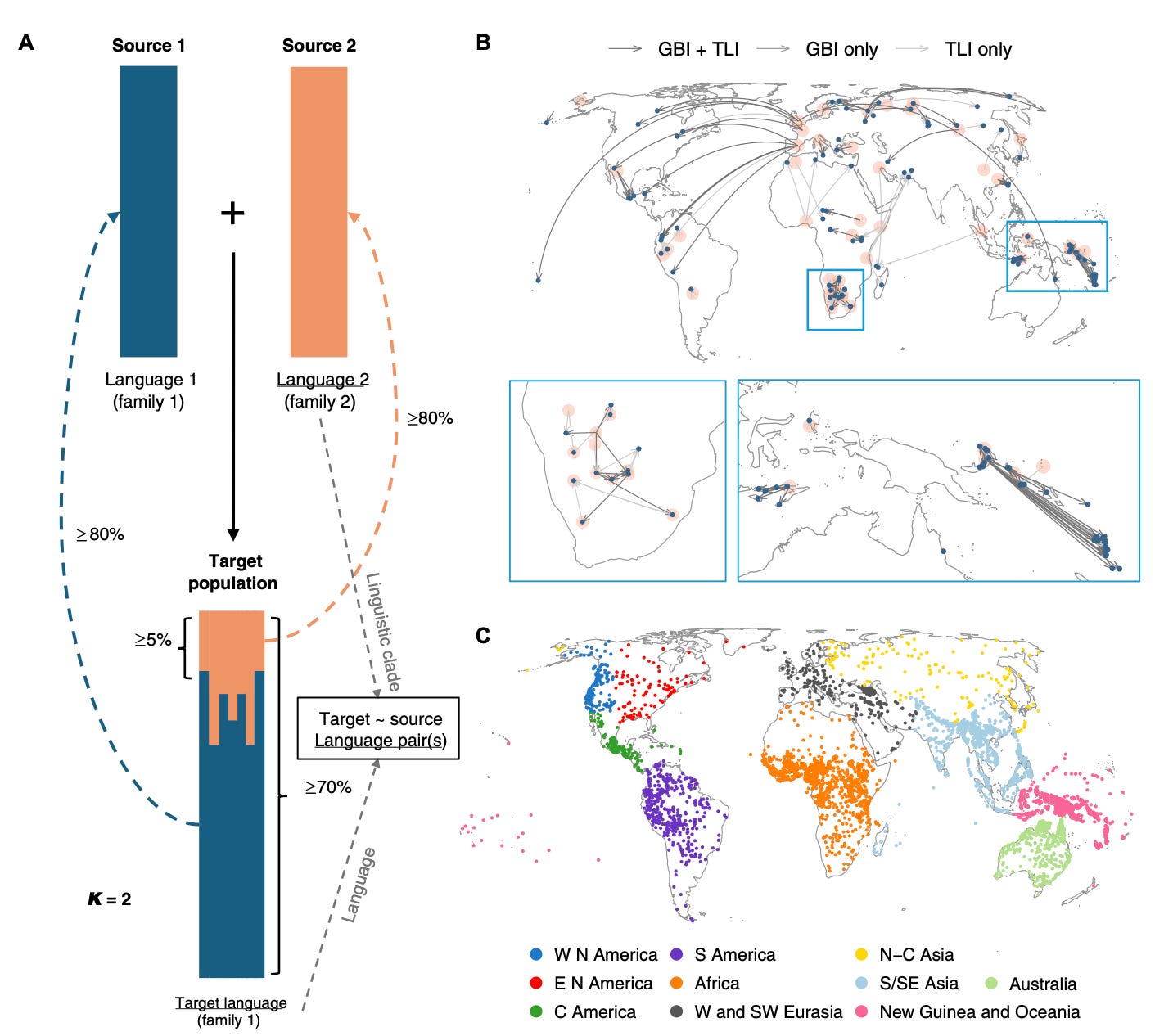

To put this hypothesis to the test, the researchers analyzed the genomes of 4,768 individuals from 558 populations around the world. Using genetic analysis tools, they identified over 125 instances where modern populations showed significant genetic admixture from two different ancestral groups. This allowed them to create a list of "contact pairs," such as the descendants of Spanish and Quechua speakers in South America, whose genomes clearly showed the legacy of an ancient interaction. Crucially, by focusing on languages from different families, they could be certain that any shared linguistic traits were the result of borrowing, not shared ancestry.

For each of these genetically-defined contact pairs, the researchers then drew on two extensive databases of linguistic features, covering grammar, phonology, and lexicon. By comparing the languages of the admixed populations with those of their ancestral sources, the team could precisely measure how much linguistic sharing had occurred. This approach bypassed the problem of missing historical records entirely, creating a systematic, global map of language contact and its outcomes.

A Quiet, Global Consistency

The most striking finding to emerge from this work was a quiet yet profound consistency. The researchers found that regardless of where in the world these populations came into contact, their languages became more similar to a "remarkably consistent extent". The probability of two languages sharing a feature state increased by approximately 4% to 9% in situations of genetic contact.

This consistency held true across a wide range of demographic and geographic conditions. It was observed whether the contact took place between populations within a single continent, such as the contact between Bantu and Khoisan languages in Zambia, or between continents, as was the case with European colonialism in the Americas. The findings indicate a consistent link between the history of human populations and the history of their languages.

The consistency of this effect suggests something fundamental about the process of linguistic change. It implies that the fact of contact itself is a more powerful and predictable force than the myriad specific details of that contact. The study's authors noted that the social dynamics, power imbalances, and geographical scale of a given encounter do not seem to alter the overall rate of borrowing in a significant way. It is as if there is a general, self-limiting rate of cultural diffusion that persists across all scenarios, constrained enough not to completely erase the vertical history of a language but powerful enough to reshape its structure.

The Curious Case of the Unborrowable Trait

For decades, the field of linguistics has held to certain assumptions about which features of a language are more likely to be borrowed. The conventional wisdom suggested that "matter borrowing," the transfer of concrete words, was common and easy, while "pattern borrowing" of sounds or grammatical structures was rare and difficult. The logic was tied to the human brain: while new vocabulary can be learned at any age, the core structures of grammar and phonology are thought to be acquired during a "critical period" in early childhood, making them less accessible to adults who initiate most borrowing.

The meta-analysis of the Graff et al. study directly challenged this long-standing assumption. When the researchers broke down their findings by linguistic feature class, the results were not what was expected. The table below illustrates some of the surprising results.

The most compelling contradiction appeared in the data on "Grammatical Categories" and "Lexical Classes". These features are notoriously difficult to acquire after early childhood, yet the study found that their borrowing rates were in a range similar to or even higher than "Lexical Semantics".

This finding suggests that the social forces at play during contact may easily override what were once considered cognitive or developmental constraints. In situations with strong demographic imbalances, such as those associated with European colonialism, there is high pressure to assimilate to a high-prestige language. The adoption of a dominant group's grammatical categories may not be a simple cognitive act but a social one, a powerful signal of assimilation and a means of gaining social standing. The study posits that a language is not just a cognitive tool but a badge of group identity, and its features can be borrowed or rejected based on social necessity, regardless of their intrinsic difficulty.

When Languages Push Back

While the study found a consistent trend toward borrowing, it also revealed a compelling counter-narrative: sometimes, languages in contact actively reject convergence. This phenomenon, known in anthropology as schismogenesis, is a process of signaling divergence, where groups in contact use linguistic differences to assert a distinct identity. The study found a noticeable number of feature states that, instead of being shared, actually became less alike under contact, a sign of this deliberate diversification.

A particularly interesting example of this dynamic appeared in the data on prosody, the rhythmic and tonal properties of speech. Prosody is a powerful marker of social belonging. The researchers found that in imbalanced, colonial-era contact, prosodic features were more likely to be borrowed, a sign of assimilation. However, in more socially balanced encounters, these same features showed a tendency for divergence, becoming a tool for distinguishing one group from another.

This dual nature of prosody illustrates a deeper truth about language and identity. The same linguistic feature can be a signal of convergence in one context and a symbol of divergence in another, depending entirely on the social power dynamics between the groups. It shows that language change is not a passive process of absorption; it is an active negotiation of identity, played out through the subtle shifts in sounds, words, and grammar.

A Legacy of Connection, and a Warning for the Future

The findings of this study are not confined to the past; they resonate deeply with the present. The history of human migration is a testament to the power of contact, from ancient displacements of farmers to recent intercontinental movements. Our world is more interconnected than ever, and these same processes of borrowing, convergence, and divergence are at work.

Consider the United States, which has historically been a polyglot nation driven by waves of immigration. Yet, it is also a place where immigrant languages frequently face extinction, often fading within a few generations as they are replaced by English. This dynamic is a modern echo of the processes the study documented. Contact can certainly lead to language loss, but as this research shows, it also reshapes the surviving languages, sometimes eroding their deeper structural diversity by making them more similar. As our world becomes increasingly globalized, the study serves as a poignant reminder that the forces of human interaction will continue to transform the map of linguistic diversity, not just by driving some languages to extinction but by changing the very character of those that survive.

Other Pathways to the Human Voice

The Graff et al. study is a story about the cultural evolution of language—how it changes once it exists. But what about the biological evolution of the capacity for language itself? This is a separate but equally fascinating thread in the fabric of human history.

Another line of research recently explored a single genetic change that may have been a key contributor to our species’ capacity for complex vocal communication. Researchers from Rockefeller University studied a single amino acid change in the NOVA1 gene that is unique to modern humans and absent in our ancient cousins, the Neanderthals and Denisovans. To understand its function, they introduced the human version of the gene into mice. The result was a surprising change in the animals' vocalizations. Baby mice called to their mothers differently, and adult males altered their mating calls. While this gene is not exclusively responsible for language, its singular change in Homo sapiens and its effect on vocal communication in another species points to a possible biological foundation for our most complex cultural trait.

The NOVA1 research and the Graff et al. study illuminate two distinct but interconnected aspects of human evolution. One is about the deep biological changes that enabled us to speak in the first place, and the other is about the constant, dynamic social forces that shape how we speak. Together, they paint a fuller picture of the human story—one in which our biological potential and our social history have always been intertwined.

Additional Research

Barbieri, C., Blasi, D., Arango-Isaza, E., Sotiropoulos, A. G., Hammarström, H., Wichmann, S.,... & Bickel, B. (2022). A global analysis of matches and mismatches between human genetic and linguistic histories. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 119(12), e2122084119. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2122084119

Patin, E., Lopez, M., Grollemund, R., Verdu, P., Harmant, C., Quach, H.,... & Quintana-Murci, L. (2017). Dispersals and genetic adaptation of Bantu-speaking populations in Africa and North America. Science, 356(6337), 543-546. DOI: 10.1126/science.aal1988

Ma, D., Abrahms, B., Allgeier, J., Newbold, T., Weeks, B. C., & Carter, N. H. (2024). Global expansion of human-wildlife overlap in the 21st century. Science Advances, 10(25), eadp7706. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adp7706

Graff, A., Graff, A., Blasi, D. E., Ringen, E. J., Bajić, V., Bavelier, D.,... & Bickel, B. (2025). Patterns of genetic admixture reveal similar rates of borrowing across diverse scenarios of language contact. Science Advances, 11(35), eadv7521. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adv7521

Xu, C., Kohler, T. A., Lenton, T. M., Svenning, J. C., & Scheffer, M. (2020). Future of the human climate niche. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 117(23), 11350-11355. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1910114117

Graff, A., Blasi, D. E., Ringen, E. J., Bajić, V., Bavelier, D., Shimizu, K. K., Pakendorf, B., Barbieri, C., & Bickel, B. (2025). Patterns of genetic admixture reveal similar rates of borrowing across diverse scenarios of language contact. Science Advances, 11(35), eadv7521. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adv7521