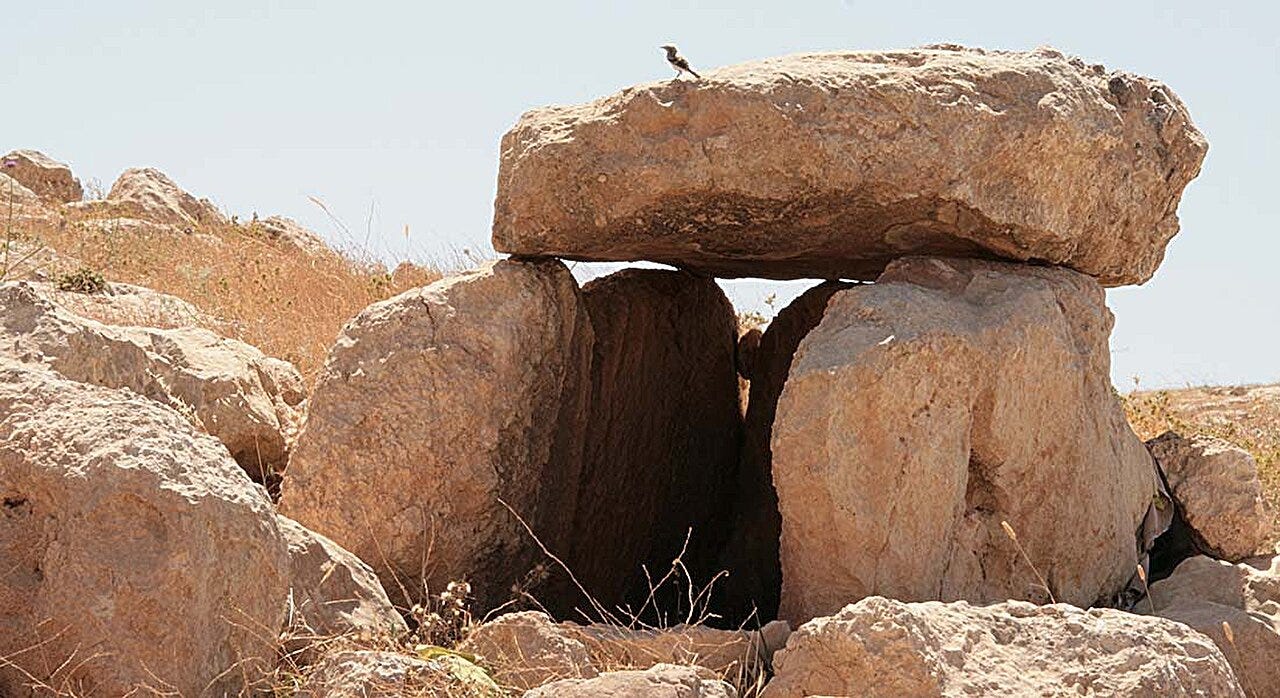

When archaeologists first walked the slopes of Murayghat, a windswept plateau south of Amman, they were struck by the stillness. The landscape was strewn with upright slabs of limestone, many collapsed but still standing in clusters. Between them lay the low outlines of circular enclosures, fragments of flint tools, and fragments of massive stone coffers that had once held the dead. Nothing about the site resembled a settlement. There were no walls, no house floors, no storage bins. Instead, it felt like a place built for gathering, for ceremony, and for remembering.

That sense of collective intention is precisely what makes Murayghat one of the most revealing discoveries of recent Near Eastern archaeology. Excavations led by Dr. Susanne Kerner of the University of Copenhagen have shown1 that around 3000 BCE, long after the decline of the Chalcolithic farming villages that once dotted the Jordan Valley, local groups began to reshape the highland landscape into something new: a monumental ritual terrain of dolmens, standing stones, and open-air sanctuaries.

The site represents not a continuation of domestic life but a transformation of it—a shift from the private spaces of homes to the shared symbolism of stone.

“Murayghat offers a rare window onto a society reinventing itself after collapse,” says Dr. Kerner. “Instead of rebuilding the same social order, people turned toward the landscape itself—using stone to anchor identity, memory, and belonging.”