The Misunderstood Meal

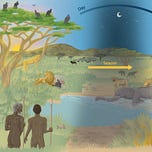

For more than half a century, the story of human evolution has been told as a triumph of the hunter. Sharp stone tools, coordinated chases across the savanna, and shared feasts around the fire have filled both textbooks and imaginations. But what if the origins of human ingenuity were less heroic—and far more opportunistic?

That is the argument advanced by Ana Mateos and Jesús Rodríguez of Spain’s Centro Nacional de Investigación sobre la Evolución Humana (CENIEH), whose new paper in the Journal of Human Evolution1 reframes scavenging as a central, adaptive behavior in hominin evolution rather than an evolutionary leftover. Their study revisits decades of archaeological, ecological, and physiological evidence through the lens of optimal foraging theory, which models how animals maximize energy gain while minimizing effort and risk.

Their conclusion: early humans may have been born scavengers, exploiting carcasses with extraordinary efficiency long before they mastered the art of the hunt.

“Scavenging was not a marginal act of desperation,” said Dr. Lucía Ferrer, a behavioral ecologist at the University of Barcelona. “It was a strategic response to the energy economy of survival, guided by intelligence, cooperation, and timing.”