A Dry Season, A Single Cow, and a Group of Hunters

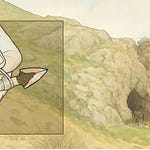

Picture a patch of the Levant around 120,000 years ago. The dry season is tightening its grip. The landscape thins to brittle stalks, gray shrubs and woody leaves. Somewhere in that parched expanse, a handful of archaic humans are tracking a single auroch cow, a towering ancestor of modern cattle and arguably one of the most dangerous animals they could have chosen to confront.

This is not a stampede. This is not a coordinated drive of dozens of animals into a trap. What the archaeological record suggests instead is quieter, slower and far more deliberate.

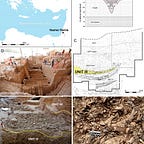

A new study in Scientific Reports1 reconstructs this ancient scene from the bones left at Nesher Ramla, a Middle Palaeolithic site that preserves one of the earliest intersections between archaic humans and Homo sapiens. Its findings are sharp enough to challenge many long-held assumptions about how our extinct cousins hunted, organized and survived.

“Selective kills indicate a rhythm of life that favored small, mobile groups rather than densely interconnected communities,” says Dr. Helena Marek, a zooarchaeologist at Tel Aviv University. “Such patterns provide a rare window into the social scaffolding of these early populations.”

The aurochs remains do not just show butchery. They tell a story of choice, timing and social scale.