In the foothills of western Iran’s Zagros Mountains, long before villages lined the valleys or fields yielded barley and lentils, small communities came together for reasons that still feel deeply familiar. They feasted. They brought offerings. And, strikingly, they brought animals from far away.

A recent study led by Petra Vaiglova and published in Communications Earth & Environment1 provides a rare glimpse into the social fabric of early Holocene lifeways. By examining the teeth of wild boars interred at the site of Asiab—dated to around 11,000 years ago—researchers have shown that at least some of these animals were not hunted locally. Instead, they were transported across rugged terrain, a considerable effort that reshapes how archaeologists understand ritual feasting and exchange before the widespread adoption of farming.

Boar Skulls and Social Geography

Excavations at Asiab revealed a cache of 19 wild boar crania, arranged and sealed within a structure near the center of the site. Cut marks on the bones suggest the animals were butchered for meat, but they were not discarded like kitchen refuse. Instead, the skulls were intentionally gathered and placed—possibly as part of a terminal ritual following a shared meal.

But what intrigued researchers was not only the burial pattern, but the origins of these animals.

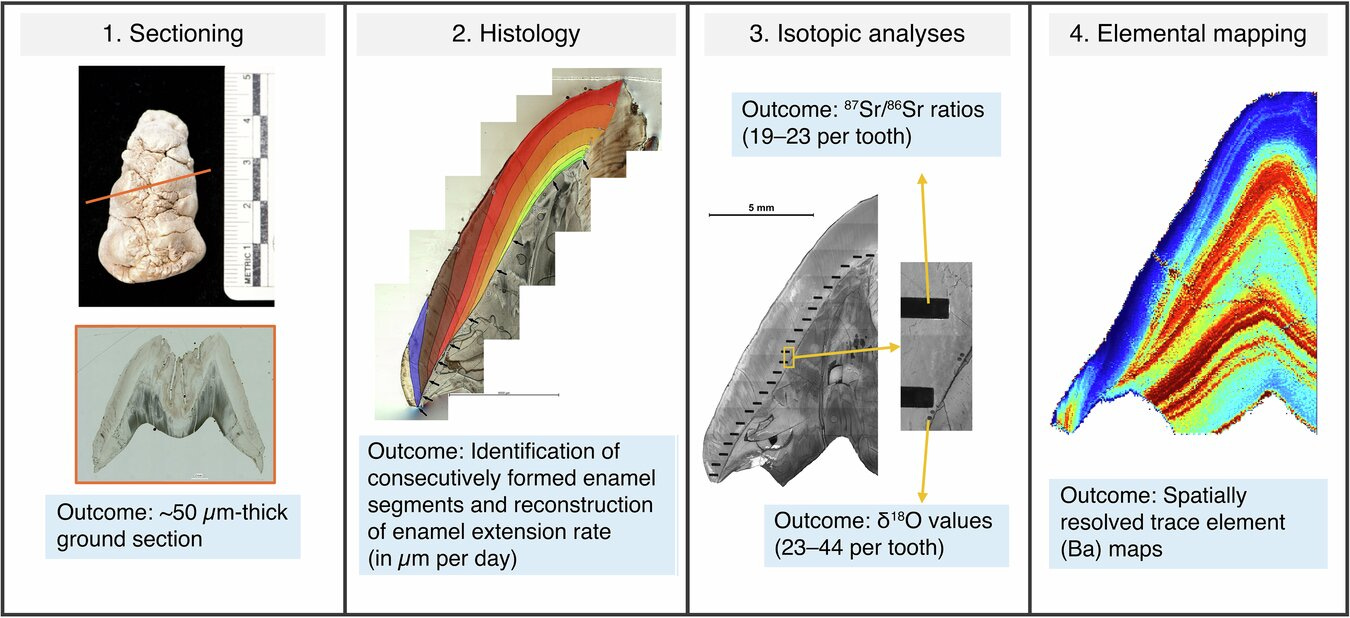

To determine how far the boars had traveled, the team used incremental isotope sampling on the tooth enamel of five specimens. Tooth enamel forms over time and captures isotopic signatures that reflect the animal’s local geology, climate, and diet. The enamel growth lines, not unlike tree rings, can be read sequentially to track movements across different environments.

The data showed that some of these animals likely came from at least 70 kilometers away, crossing multiple ecozones and elevations. Given the jagged topography of the region, such distances would have taken multiple days to traverse, whether by human transport or via extended hunting expeditions.

"The variability in isotope ratios strongly suggests that at least a subset of the boars was not local to Asiab. Their presence at the feast implies either long-distance transport or coordinated social exchange across territories," the authors wrote.

A Ritual Economy Before Agriculture

The presence of distant boars at Asiab comes at a pivotal time in human history: the cusp of the Neolithic. While the cultivation of cereals and the domestication of animals would not fully take hold for another few centuries, communities in the Zagros were already deeply engaged in seasonal mobility and communal gathering.

Feasting is often seen as a marker of agricultural surplus. But the Asiab evidence shows that ritual consumption and symbolic gifting predated stable food production. Like the famed Durrington Walls pig feasts near Stonehenge, where isotope data showed animals were brought from across Britain, the boar skulls of Asiab appear to represent a form of social signaling—one that commemorated place and reinforced ties across foraging groups.

"Reciprocity lies at the heart of social interaction. The transport of animals across distances—especially when local game was available—suggests symbolic motives tied to identity, kinship, and landscape," the authors explained.

Food, as both gift and performance, becomes a canvas for social memory. And in a world without written records, animal transport may have served as an embodied message: “This is where I come from.”

Mobility, Memory, and the Meaning of Meat

It’s tempting to think of pre-agricultural groups as isolated or simple. But the isotopic evidence from Asiab complicates that view. It indicates not just mobility, but intentionality. Certain animals were selected and carried to this location for reasons that had more to do with meaning than meat.

This might have been a moment of seasonal aggregation—where dispersed groups came together to reaffirm social bonds. Or perhaps it marked a liminal event, a shift in leadership, or a shared ritual of renewal. Whatever the purpose, the archaeological footprint is clear: these early Holocene groups were engaging in coordinated, effortful behavior to create shared experience.

Reading the Past in Enamel and Earth

Like many recent bioarchaeological advances, the study hinges on techniques that can make the invisible visible. By slicing boar teeth into ultra-thin sections, the team revealed subtle shifts in oxygen and strontium isotope values over time. These chemical signatures offer a record of environmental exposure that only a few decades ago would have been unknowable.

This approach, known as sequential microsampling, can reconstruct an animal’s geographic journey from birth to death. In doing so, it also sketches the movements and choices of the humans who hunted or transported them.

A Wider Pattern of Pre-Agricultural Feasting?

The Zagros evidence is not isolated. Other sites across western Asia and Europe are beginning to show signs that early Holocene feasting, long assumed to be a byproduct of farming, may in fact have played a role in precipitating it.

At Göbekli Tepe in southeastern Turkey, for example, large-scale feasting seems to predate full domestication. The accumulation of food waste, butchered animal remains, and ceremonial architecture there points to organized gatherings that required surplus and coordination. Whether hunting and gathering could support such events without agriculture has been the subject of considerable debate.

Asiab now adds a data point that firmly places feasting at the doorstep of the Neolithic. And it highlights a critical insight: that early humans were not passive recipients of ecological change. They actively shaped their social world through movement, gifting, and ritualized consumption.

Related Research:

Madgwick, R., Lamb, A., Sloane, H., & Evans, J. (2019). Multi-isotope analysis reveals that feasts in Stonehenge's shadow drew pigs from across Britain. Science Advances, 5(3), eaau6078. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aau6078

Twiss, K. C. (2008). Transformations in an early agricultural society: Feasting in the Southern Levantine Pre-Pottery Neolithic. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 27(4), 418–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaa.2008.06.003

Benz, M. (2010). Pre-pottery Neolithic B animal management in the Northern Fertile Crescent: The evidence from Göbekli Tepe. Documenta Praehistorica, 37, 203–218. https://doi.org/10.4312/dp.37.13

Vaiglova, P., Kierdorf, H., Witzel, C., Falster, G., Joannes-Boyau, R., Wang, Y., Wu, J., Williams, I., Knowles, B., Wu, Y., Bangsgaard, P., Yeomans, L., Richter, T., & Darabi, H. (2025). Transport of animals underpinned ritual feasting at the onset of the Neolithic in southwestern Asia. Communications Earth & Environment, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02501-z