In the heart of the Pacific, across a constellation of remote islands, the stones still stand. Upright, weathered, and often enigmatic, they were once focal points of sacred gatherings. Their presence hints at a far more intricate and dynamic history of cultural exchange and monument-building in East Polynesia than previously believed. New archaeological research now reshapes the narrative of how ritual space evolved from ephemeral courts to massive megaliths across thousands of kilometers of ocean.

A recent synthesis by Paul Wallin and Helene Martinsson-Wallin of Uppsala University, published in Antiquity1, examines hundreds of radiocarbon dates and stratigraphic sequences from across Polynesia. Their analysis calls into question the conventional west-to-east trajectory of religious architecture in the Pacific. Instead, it suggests a model of multidirectional innovation and influence, with ritual ideas often flowing just as forcefully from east to west.

"We place importance on networks between islands or island groups, through which new ideas were also transferred from east to west, as well as on later internal developments."

The Old Story: One-Way Diffusion

For decades, archaeologists and anthropologists working in the Pacific adhered to a fairly linear model: settlers expanded from West Polynesia (Tonga and Samoa) eastward, bringing with them language, crops, social organization, and sacred architecture. The assumption was that marae—the open-air ritual spaces demarcated with stone uprights and platforms—spread like beads on a necklace, from core to periphery.

That story is no longer sufficient. The authors argue that while initial settlement did follow a west-to-east path, the subsequent development of religious architecture was more dynamic. In particular, the island of Rapa Nui (Easter Island) may have taken on a central, rather than peripheral, role in the innovation of ritual forms.

Phase One: The Rituals of Arrival (c. AD 1000–1300)

During the early centuries of colonization, ritual spaces were defined more by actions than by permanent structures. Archaeological evidence from the Cook Islands, Society Islands, and Marquesas reveals upright stones associated with ovens, burials, and feasting pits. These modest features marked sacred zones where ancestral spirits were honored, communal meals were shared, and cosmological ties reaffirmed.

Sites such as Motu Tapu on Rarotonga and Vaito'otia on Huahine show that even in these early moments of contact, Polynesians were reshaping the landscape with spiritual intent. The consistent use of stone uprights suggests a shared symbolic vocabulary that settlers carried across the sea.

Phase Two: Monumentalization and Feedback (c. AD 1300–1600)

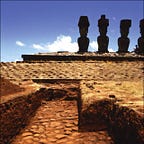

It is in the centuries after initial settlement that the story begins to shift. Rather than simply elaborating earlier West Polynesian forms, island societies began to create new architectural expressions. On Rapa Nui, the first stone platforms, or ahu, began to rise, anchoring moai statues in a formalized sacred landscape.

"Contrary to the early dispersal of open ritual spaces that followed the West to East settlement pattern, our assessment of the development of the early ahu/marae complex begins in the far East Polynesian island of Rapa Nui."

From this eastern outpost, the idea of consolidating sacred space into highly visible, stone-built platforms appears to have traveled back toward the center. Radiocarbon data suggest that formal marae with ahu began appearing later in the Society and Cook Islands than on Rapa Nui. Far from being an isolated anomaly, the moai and their platforms may have catalyzed a wave of architectural change across East Polynesia.

Phase Three: Hierarchy in Stone (c. AD 1600–1765)

In the final phase of this model, large-scale megalithic constructions proliferated across islands such as Tahiti, Raiatea, and Hawai‘i. These temples were no longer just sacred spaces; they were assertions of political authority. Marae like Taputapuatea on Raiatea and the stepped heiau of Hawai‘i became stages for state rituals, warfare ceremonies, and the public performance of chiefly power.

By the time Europeans arrived, many of these islands had developed into complex polities with rigid hierarchies, genealogical priesthoods, and architectural traditions that dwarfed earlier phases. The stones still carried spiritual meaning, but they also bore the weight of social control.

Rethinking Isolation

The idea that Rapa Nui developed in near-total isolation has been a cornerstone of Pacific archaeology. This paper suggests otherwise. Genetic evidence points to pre-European contact with South America, and now ritual architecture appears to show signs of outward influence. The easternmost island of Polynesia may have seeded ideas that later reshaped religious life across the central Pacific.

"Based on our contextual assessment of ritual space and place, we suggest that the materialisation of ritual space developed earlier in the eastern part of East Polynesia, with ideas then spreading through established networks in an east-to-west direction."

Toward a New Cartography of Sacred Space

Wallin and Martinsson-Wallin propose a tripartite model: an initial phase of dispersed, shared practices; a second phase of monumental formalization; and a final phase of hierarchical elaboration. Rather than a one-way diffusion, the data point to a braided network of innovation, adaptation, and symbolic dialogue among distant island communities.

This work invites archaeologists to look beyond static models of migration and consider ritual spaces as dynamic arenas shaped by interaction, environment, and ideology. The upright stones and massive platforms that still mark these islands are not just remnants of past beliefs, but records of how those beliefs traveled, changed, and came to define the sacred.

Related Research

Ioannidis, A. G., Blanco-Portillo, J., Sandoval, K., et al. (2020). Paths and timings of the peopling of Polynesia inferred from genomic networks. Nature, 597, 522–526. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03902-8

Moreno-Mayar, J. V., Lipson, M., Renaud, G., et al. (2024). Ancient Rapanui genomes reveal resilience and pre-European contact with the Americas. Nature, 633, 389–397. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07881-4

Weisler, M. I. (1998). Hard evidence for prehistoric interaction in Polynesia. Current Anthropology, 39(4), 521–532. https://doi.org/10.1086/204758

Sharp, W. D., Kahn, J. G., Polito, C. M., & Kirch, P. V. (2010). Rapid evolution of ritual architecture in central Polynesia indicated by precise 230Th/U dating. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(30), 13234–13239. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1005063107

Kahn, J., & Kirch, P. V. (2014). Monumentality and Ritual Materialization in the Society Islands. Bishop Museum Press.

Wallin, P., & Solsvik, R. (2014). The place of the land and the seat of the ancestors: Temporal and geographical emergence of the classic East Polynesian marae complex. Kon-Tiki Museum Occasional Papers, 12, 79–107.

Wallin, P., & Martinsson-Wallin, H. (2025). From ritual spaces to monumental expressions: rethinking East Polynesian ritual practices. Antiquity, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2025.10096