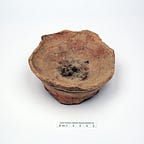

At first glance, the ceramic burners dug from Iron Age homes in northwest Arabia might seem mundane—cracked bowls of fired clay, their soot-blackened interiors whispering of fire long extinguished. But inside their walls lay something far more enduring than ash: the faint, molecular traces of Peganum harmala, or Syrian rue, a psychoactive and medicinal plant still used across the region today.

New research1 from a collaborative team of archaeologists and chemists has uncovered the earliest material evidence of this plant's use in Arabian fumigation rituals. Through meticulous chemical analysis, scientists were able to isolate alkaloid residues in household incense burners from the ancient oasis settlement of Qurayyah, dating to the first half of the first millennium BCE. What emerged was a picture not just of ancient drug use, but of a deeply embedded domestic tradition—one that blurred the boundaries between health, ritual, and scent.

A Scented Signal from the Past

The story begins in the northern Hijaz, at the site of Qurayyah—a bustling Iron Age oasis community surrounded by arid highlands. Here, archaeologists uncovered several ceramic censers from residential compounds. These weren’t grave goods or temple offerings; they were found in kitchens and cellars, hinting at a more intimate use.

From these vessels, researchers extracted organic residues using high-performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS), a tool capable of detecting even minute quantities of complex molecules. Among the molecular ghosts were harmine and harmane, beta-carboline alkaloids known to occur in Peganum harmala.

“This discovery represents not only the first evidence for its use in Iron Age Arabia, but also the most ancient, radiometrically dated material evidence of Peganum harmala being used for fumigation globally,” the authors write.

Unlike other psychoactive plant finds that often appear in ceremonial or burial contexts, this one is different. The harmala residue was located inside burners used in everyday domestic settings, suggesting that the plant was being used not for elite ritual, but likely for routine household purposes.

Smoke for Health, Not Hallucinations

Today, Peganum harmala is still used in traditional Arabian medicine. Its seeds are burned to ward off illness, ease headaches, treat arthritis, and even repel insects. In the Qurayyah samples, the alkaloid traces were found alongside plant sterols and triterpenoids, chemical signatures pointing to seed oils and resins.

The researchers suggest that the most likely use of the plant was medicinal or sanitary. In small doses, harmala alkaloids act as mild sedatives, antidepressants, and anti-inflammatories. Their antibacterial properties may have made them especially valuable in arid, crowded settlements like Qurayyah.

"The use of Peganum harmala at the oasis was most likely for domestic purposes connected to the household rather than for public ceremonies or funerary rituals," the authors note.

It is true that in high doses, these compounds can cause hallucinations—and indeed, Peganum harmala has been used for centuries in shamanic or religious contexts across the Middle East and Central Asia. But there is no indication the Qurayyah residents were seeking transcendence through smoke. If anything, the plant's bitter odor and astringent effects likely made it a better tool for purification than for ecstasy.

Tracing a Pharmacological Heritage

Part of what makes this discovery significant is not only its antiquity, but its continuity. Syrian rue is still burned in Saudi homes to this day. In some traditions, it is lit to ward off the evil eye; in others, its smoke purifies the air during illness. What the Qurayyah censers show is that this lineage of knowledge stretches back nearly three millennia.

“This discovery shows the deep historical roots of traditional healing and fumigation practices in Arabia,” said Ahmed Abualhassan of the Saudi Heritage Commission, co-author of the study.

In contrast to many parts of the ancient world, where medicinal knowledge was recorded in texts, much of Arabia’s healing tradition has been passed down orally. That makes chemical residue analysis all the more powerful, offering a rare, tangible record of plant-based practice.

Practical Wisdom in Clay

Perhaps the most compelling part of this story is its sheer pragmatism. While it’s tempting to think of drug use in the ancient world as mystical or elite, the Qurayyah data suggests otherwise. Here were everyday people managing pain, fending off infection, and scenting their homes with the best tools they had: local plants, fire, and memory.

This wasn’t a hallucinogenic rite of passage or a burial rite; it was Tuesday.

The authors argue that fumigation with Peganum harmala likely served several roles at once: therapeutic, hygienic, perhaps even emotional. Burning the seeds released smoke that might soothe sore joints, disinfect a crowded room, or simply offer reassurance through a familiar smell.

There is also the possibility, however speculative, that the act itself was ritualistic in the most ordinary sense—a daily rhythm of care and belief passed on in gestures rather than words.

The Past Smolders On

As scholars continue to trace the uses of medicinal and psychoactive plants across time, finds like this one add nuance to our understanding. The history of drug use isn’t just a history of ecstatic visions and sacred texts. It is also the history of headaches soothed, children protected, homes cleansed, and bodies laid to rest with dignity.

The scent of Peganum harmala may not be universally pleasant. But in Qurayyah, it lingered long enough to tell a story that had, until now, only lived in memory.

Related Research

Guerra-Doce, E. (2015). Psychoactive substances in prehistoric times: examining the archaeological evidence. Time and Mind, 8(1), 91–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/1751696X.2014.993244

Robinson, D. W., et al. (2020). Datura quids at Pinwheel Cave, California, provide unambiguous confirmation of the ingestion of hallucinogens at a rock art site. PNAS, 117(49), 31026–31037. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2014529117

Tanasi, D., et al. (2024). Multianalytical investigation reveals psychotropic substances in a Ptolemaic Egyptian vase. Scientific Reports, 14, 27891. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-27891-9

Ren, M., et al. (2019). The origins of cannabis smoking: chemical residue evidence from the first millennium BCE in the Pamirs. Science Advances, 5(7), eaaw1391. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aaw1391

Huber, B., Luciani, M., Abualhassan, A. M., Giddings Vassão, D., Fernandes, R., & Devièse, T. (2025). Metabolic profiling reveals first evidence of fumigating drug plant Peganum harmala in Iron Age Arabia. Communications Biology, 8(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08096-7