A New Kind of Toolkit

It’s easy to imagine the earliest humans armed with chipped stones, stalking game across windswept plains. But at a site called Gantangqing in Yunnan Province, the story1 told in the soil is quieter and perhaps more surprising.

There, researchers uncovered 35 wooden tools buried in a clay-heavy lakeshore deposit. Preserved for roughly 300,000 years, these implements suggest a very different kind of daily life: one spent foraging along wetland margins, extracting underground food with carved digging sticks and hook-shaped root cutters.

“These tools speak to a different subsistence strategy than we typically associate with the Paleolithic. It’s a portrait of hominins who worked the land not just with force, but with foresight,” said archaeologist Gao Xing, one of the study's senior contributors.

Why Wood Rarely Speaks

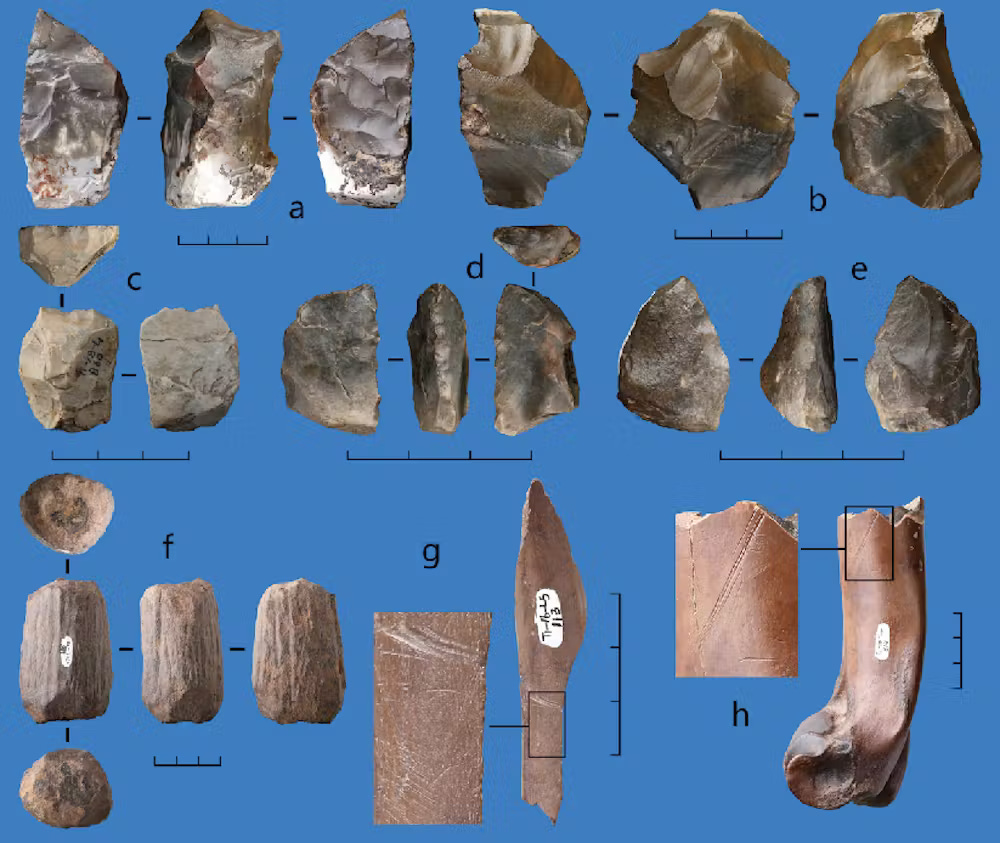

Stone tools dominate the archaeological record not because they were the only implements used, but because they survive. Wood, by contrast, decays quickly unless sealed in unusually wet, dry, or oxygen-poor conditions. At Gantangqing, the ancient shoreline of Lake Fuxian created the perfect anaerobic environment to preserve the wooden artifacts.

The result is one of the most significant Early Paleolithic woodworking assemblages ever discovered outside Africa or western Eurasia. And unlike the fragmentary wooden finds from sites like Clacton (UK) or Florisbad (South Africa), the Gantangqing tools are largely intact and functionally diverse.

Tools with a Purpose

The assemblage includes:

Two large digging sticks, built for two-handed use

Four hook-shaped implements, likely for root cutting

Dozens of small, one-handed tools for foraging or processing plant material

Most of the tools were shaped from pine wood, though a few came from local hardwoods. Microscopic analysis revealed scrape marks, polished surfaces, and wear patterns consistent with heavy, repeated use. Some even held soil residues or bore parallel streaks from digging.

“These were not ad hoc pieces of wood picked up on a whim,” said co-author Dennell Robin. “They were shaped deliberately, maintained, and likely reused across seasons.”

Dating Deep Time

To determine the age of the site, the team applied infrared stimulated luminescence to over 10,000 individual mineral grains, bracketing the tools’ depositional window between 360,000 and 250,000 years ago. A mammal tooth dated independently to around 288,000 years ago helped confirm the estimate.

This places the Gantangqing site squarely within the later part of the Middle Pleistocene, a period marked by key behavioral shifts among archaic humans.

A Lush and Edible Landscape

Sediment cores revealed pollen from over 40 plant families. Charcoal, animal bones, and macrofossils added further detail. The Gantangqing environment was a mosaic of grassland, forest, and lakeshore wetland, inhabited by turtles, birds, rhinos, and likely early hominins.

The plants were just as telling. There were edible nuts (pine, hazel), berries, kiwi vines, grapevines, and tuber-bearing aquatic plants. These were not random finds. They were seasonal foods with distinct harvesting needs.

“You don’t casually dig up aquatic tubers,” said paleoethnobotanist Liu Jianhua. “You need to know where and when they grow, and you need the right tools.”

Rethinking Stone Age Diets

The Gantangqing hominins were not only making tools from wood but also shaping a foraging economy centered on plants. This stands in contrast to sites like Schöningen in Germany, where roughly contemporaneous wooden spears point to a focus on large animal hunting.

“The dominant narrative of early human evolution still leans toward the carnivore,” said Gao. “But in the humid subtropics of southwest China, a plant-rich diet may have been key.”

This discovery adds nuance to long-held assumptions about early human subsistence strategies and tool use in East Asia, where the so-called “Movius Line” once implied a lag in technological development.

More Than Tools, A Way of Life

At Gantangqing, woodworking was not a marginal activity. It was essential to survival. And because wood so rarely survives in the archaeological record, this window into Paleolithic life may have remained closed without the unique preservation conditions at the site.

“These wooden tools are eloquent in their simplicity,” said Liu. “They show a sophisticated relationship with plants, environments, and the rhythms of a landscape that sustained generations.”

Related Research

Here are several studies that complement the Gantangqing findings:

MacDonald, K., & Roebroeks, W. (2022). “The ecology of Neanderthal woodworking.” Nature Ecology & Evolution, 6, 113–118. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-021-01641-9

Gaudzinski-Windheuser, S., et al. (2020). “Evidence for early hominin wood-working from Schöningen, Germany.” Nature Ecology & Evolution, 4, 712–719. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-020-1139-x

Plummer, T. W. (2004). “Flaked stones and old bones: Biological and cultural evolution at the dawn of technology.” Yearbook of Physical Anthropology, 47(S39), 118–164. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.20157

Liu, J.-H., Ruan, Q.-J., Ge, J.-Y., et al. (2025). 300,000-year-old wooden tools from Gantangqing, southwest China. Science, 389(6755), 78–83. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adr8540

Liu, J.-H., Ruan, Q.-J., Ge, J.-Y., Huang, Y.-J., Zhang, X.-L., Liu, J., Li, S.-F., Shen, H., Wang, Y., Stidham, T. A., Deng, C.-L., Li, S.-H., Han, F., Jin, Y.-S., O’Gorman, K., Li, B., Dennell, R., & Gao, X. (2025). 300,000-year-old wooden tools from Gantangqing, southwest China. Science (New York, N.Y.), 389(6755), 78–83. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adr8540