In a lake basin in what is now eastern Germany, Neanderthals once worked amid piles of shattered bone, warmed by the glow of firelight and the fat-rich scent of boiling marrow. They were not simply scavenging leftovers from hunts. They were crafting calories with purpose. New research from the Neumark-Nord 2 site, published in Science Advances1, provides compelling evidence that Neanderthals were systematically extracting bone grease 125,000 years ago—long before modern humans appeared in Europe.

This site is more than just a scatter of artifacts. It represents a logistical outpost, a place where at least 172 large animals—horses, aurochs, and red deer—were brought and broken down. This was no random butchery. The bones were crushed, fragmented, and likely boiled in makeshift containers to extract a vital nutrient: fat.

"Hunter-gatherers reliant on meat cannot survive on protein alone. They need fat or carbohydrates to stay alive. This study shows Neanderthals were aware of that and acted accordingly."

Understanding Fat as Lifeline

Protein has limits. The human body can only metabolize a certain amount of it before toxicity sets in. This condition, known as "rabbit starvation," was a real danger for Ice Age peoples who relied heavily on lean game. To survive, they needed dietary fat—and in cold seasons, when plant foods were scarce, that meant unlocking it from within bones.

Bone grease is rich in calories and stored in the spongy interiors of long bones and joints. Rendering it is no small task: bones must be smashed into small fragments, often with stone hammers and anvils, then boiled to release the lipid-rich content.

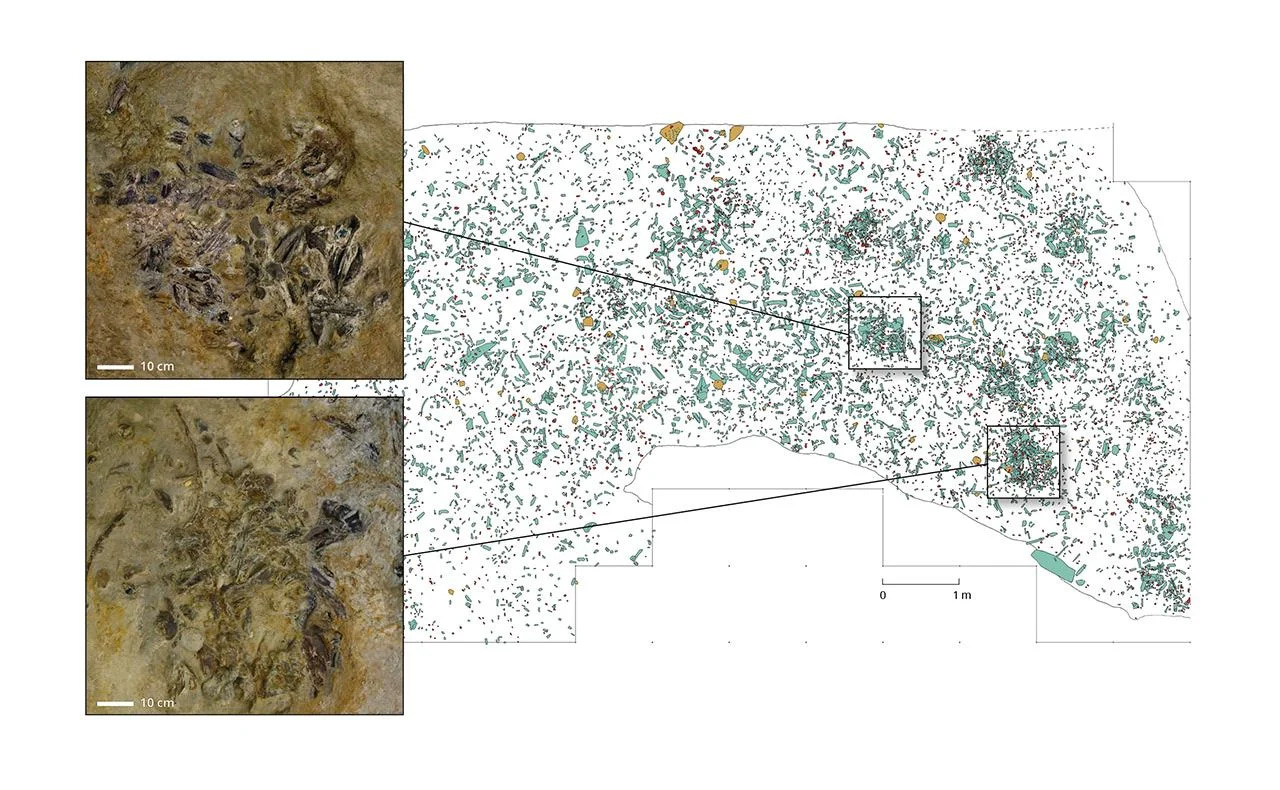

At Neumark-Nord, archaeologists found more than 118,000 bone fragments, the vast majority under 3 centimeters long. Spatial clustering revealed specialized processing zones littered with flint tools, hammerstones, anvils, and fire residues. Long bones bearing traces of marrow were concentrated in one area; foot bones, which offer little nutritional return, were scattered elsewhere.

"The intensity of fragmentation, the types of bones selected, and the clustering of tools and fire-altered material strongly suggest this was a dedicated fat-processing site."

A Site Frozen in Time

The NN2 basin was a shallow body of water that likely functioned as a seasonal processing hub. Sediment buildup preserved artifacts in place, avoiding the typical erosion and mixing that plague open-air Paleolithic sites. Stratigraphic analysis suggests that this concentration of activity took place over a short time span, perhaps a few decades or even years.

This was not a campsite. There were no hearths, no sleeping areas. It was a place to work. Neanderthals transported select body parts from carcasses across the landscape and brought them here—perhaps from distant kills or even caches stored for later use.

"The edge of the lake provided water, fuel, and access to lithic materials. It was a perfect setting for intensive grease rendering."

Rethinking Neanderthal Ingenuity

The findings challenge long-held assumptions about Neanderthal behavior. Intensive bone fat processing has traditionally been associated with Upper Paleolithic modern humans, who were thought to be more sophisticated foragers. But this study pushes the timeline back nearly 100,000 years.

Moreover, it suggests Neanderthals practiced resource intensification—getting the most out of each kill. This required planning, knowledge of fat-rich skeletal parts, and coordinated labor. It also implies some form of delayed consumption: either storing grease for later or integrating it into communal meals.

"Neanderthal diets were not haphazard. They showed nuanced understanding of nutritional value and knew how to engineer calories from challenging sources."

Implications for Human Evolution

Sites like Neumark-Nord hint at broader questions. Did other Middle Pleistocene hominins engage in similar practices? Have archaeologists missed similar evidence elsewhere because of poor preservation? And most intriguingly: does this kind of behavior speak to a form of social organization more complex than previously thought?

The labor-intensive nature of grease rendering suggests cooperation. It's hard to imagine an individual cracking thousands of bones alone. Instead, the work likely unfolded in small groups—each person playing a role, each fire carefully tended.

And then there’s the ecological dimension. Across the Neumark-Nord landscape, Neanderthals harvested hundreds of herbivores, including elephants and rhinos. Their activities left an ecological footprint, one that may have shaped faunal populations during a key interglacial window.

"We are glimpsing a Paleolithic food economy that was already sophisticated. Neanderthals weren’t just surviving. They were managing landscapes, resources, and perhaps even memory."

A Legacy in Fat and Fire

As research expands into other interglacial sites, and as archaeological techniques refine, more signs of this behavior may emerge. The Neumark-Nord "fat factory" provides a potent reminder that the Paleolithic world was one of innovation and adaptation—not limited to our own species.

The Neanderthals who labored by that ancient lake shore knew the value of fat. And in a world of bitter cold, scarce carbohydrates, and lean meat, they found a way to keep warm, to think clearly, to carry on. One shattered bone at a time.

Additional Related Research

Blasco, R., Rosell, J., Peris, J. F., Arsuaga, J. L., & Carbonell, E. (2013). Environmental availability, behavioral diversity and meat procurement strategies in the Middle Pleistocene: the case of TD10-1 (Gran Dolina, Sierra de Atapuerca, Spain). Quaternary Science Reviews, 70, 136–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2013.03.002

Speth, J. D. (2010). The Paleoanthropology and Archaeology of Big-Game Hunting: Protein, Fat, or Politics? Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-6733-6

Morin, E. (2007). Fat composition and Nunamiut decision-making: a new look at the marrow and bone grease indices. Journal of Archaeological Science, 34(1), 69–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2006.03.015

Blasco, R., Rosell, J., & Gopher, A. (2019). Subsistence behaviors and exploitation of animal resources in the Lower Paleolithic: The case of Qesem Cave (Israel). Quaternary International, 515, 7–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2018.11.003

Speth, J. D., & Spielmann, K. A. (1983). Energy source, protein metabolism, and hunter-gatherer subsistence strategies. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 2(1), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/0278-4165(83)90002-6

Kindler, L., Gaudzinski-Windheuser, S., Scherjon, F., Garcia-Moreno, A., Smith, G. M., Pop, E., Speth, J. D., & Roebroeks, W. (2025). Large-scale processing of within-bone nutrients by Neanderthals, 125,000 years ago. Science Advances, 11(27). https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adv1257