In two cemeteries on England’s south coast, archaeologists have found something that rewrites the quiet assumptions about early medieval Britain. Among the graves of the 7th century, nestled between the burials of people with familiar northern European or western British ancestry, lie two individuals whose family stories reached far beyond the North Sea or the Channel. Genetic analysis shows that each had a paternal grandparent from West Africa.

The findings come from two separate sites: Updown in Kent1 and Worth Matravers in Dorset2. The projects, published in Antiquity, blend archaeology and ancient DNA to probe who these people were and how they were remembered by their communities.

Kent’s continental gateway

Kent has long been known as a historical crossroads, absorbing influences from the continent. In the 6th century, it experienced what archaeologists describe as its “Frankish phase,” a time of intensive connection to mainland Europe. Updown cemetery lies near Finglesham, a royal center in early Kentish politics.

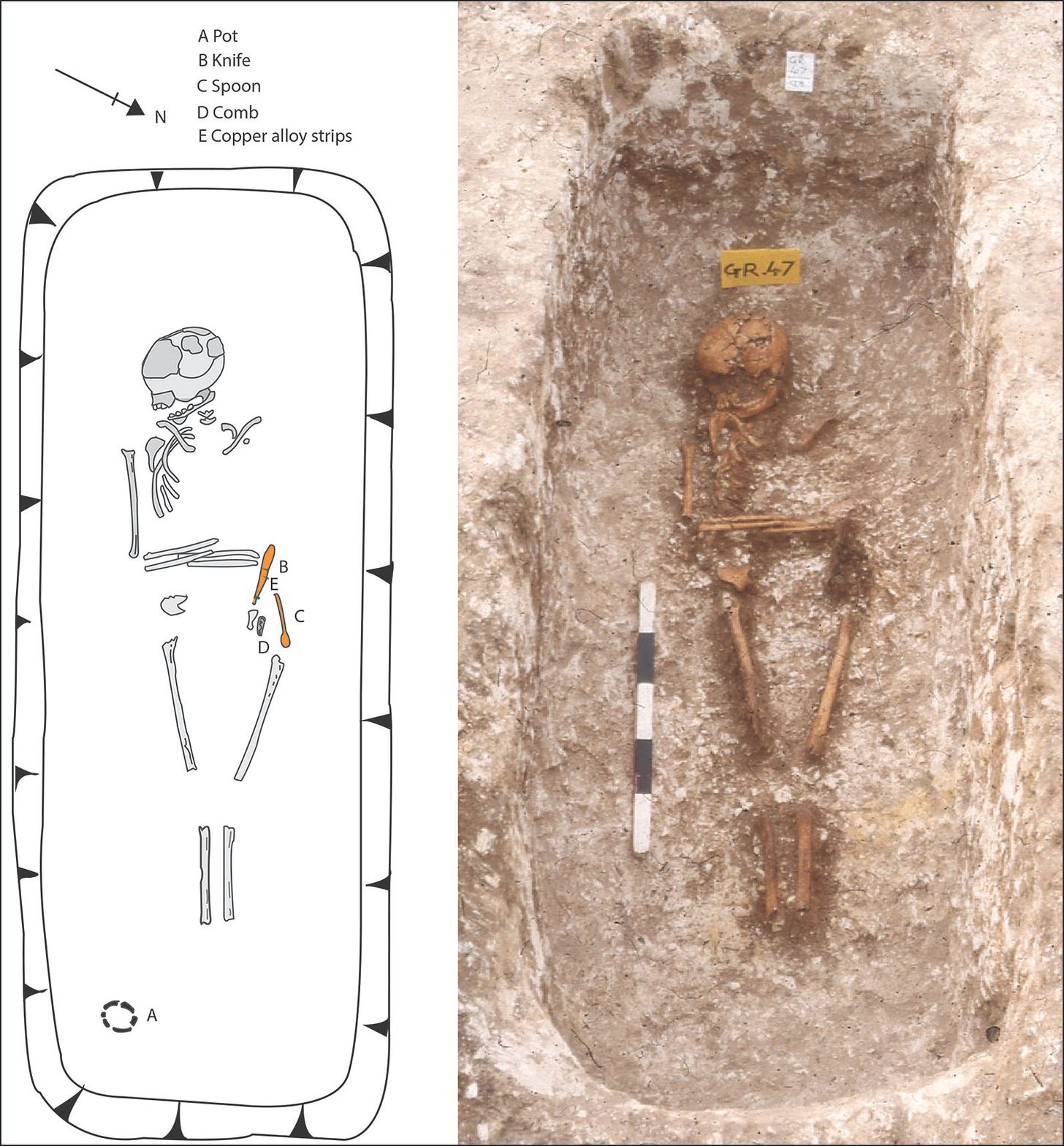

The burial with West African ancestry here contained a pot likely imported from Frankish Gaul and a spoon possibly tied to Christian ritual. These artifacts, alongside the DNA results, hint at a life entangled in trade routes and political networks that reached deep into Europe and, indirectly, into Africa.

Dorset’s western edge

The second individual, buried at Worth Matravers on the Dorset coast, lived in a region less saturated by Anglo-Saxon influence and more connected to Britain’s sub-Roman west. Here, the grave goods tell a different story: a local limestone anchor and the presence of another individual of British ancestry in the same burial.

Yet in both cases, there is no sign these individuals were treated as outsiders. They were interred according to local customs, suggesting they were accepted and integrated into their communities.

“It is significant that it is human DNA—and therefore the movement of people, not just objects—that is now starting to reveal the nature of long-distance interaction to the continent, Byzantium, and sub-Saharan Africa,” notes archaeologist Duncan Sayer.

Kinship and connection

One of the most intriguing aspects is that both individuals carried northern European mitochondrial DNA—passed down maternally—paired with autosomal DNA linking them to present-day Yoruba, Mende, Mandenka, and Esan groups. This pattern implies that their fathers, or paternal grandfathers, were of recent West African origin, while their maternal lines were local.

The evidence pushes beyond the idea of exotic goods arriving through intermediaries. Here, it is people themselves who embody the connections, suggesting a more cosmopolitan and diverse early medieval England than often imagined.

A broader view of mobility

The discoveries fit into a growing pattern: the early medieval world was not a static map of closed ethnic zones, but a dynamic network of movements, marriages, and cultural blending. Long-distance mobility—whether through trade, diplomacy, or enslavement—could bring people from vastly different origins into new communities.

At both Updown and Worth Matravers, the archaeological record shows that such newcomers were fully integrated. The graves reveal no social marginalization in death, even if their life stories may have been marked by difference.

The authors stress that these findings, though based on just two individuals, demonstrate the potential of ancient DNA to illuminate histories that traditional archaeology alone might miss. They open new questions about how such connections were made—whether through Mediterranean trade, northern European maritime networks, or other routes that remain to be mapped.

Related research:

Schiffels, S., & Wang, K. (2020). Inferring human population size and separation history from multiple genome sequences. Nature Genetics, 52, 674–681. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-020-0625-5

– Discusses genetic modeling methods relevant to interpreting ancient DNA in historical contexts.Lazaridis, I., et al. (2022). Genetic origins of the Minoans and Mycenaeans. Nature, 548, 214–218. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature23310

– Demonstrates the role of genetic analysis in tracing complex ancestries in ancient populations.Olalde, I., et al. (2018). The Beaker phenomenon and the genomic transformation of northwest Europe. Nature, 555, 190–196. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature25738

– Shows how mobility and ancestry shifts shaped European populations during prehistory.Hellenthal, G., et al. (2014). A genetic atlas of human admixture history. Science, 343(6172), 747–751. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1243518

– Offers a global framework for understanding human genetic mixing, including African–European interactions.

Foody, M. G. B., Dulias, K., Justeau, P., Ditchfield, P. W., Ladle, L., Gretzinger, J., Schiffels, S., Reich, D., Kenyon, R., Sayer, D., Richards, M. B., Pala, M., & Edwards, C. J. (2025). Ancient genomes reveal cosmopolitan ancestry and maternal kinship patterns at post-Roman Worth Matravers, Dorset. Antiquity, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2025.10133

Sayer, D., Gretzinger, J., Hines, J., McCormick, M., Warburton, K., Sebo, E., Dulias, K., Pala, M., Richards, M., Edwards, C. J., & Schiffels, S. (2025). West African ancestry in seventh-century England: two individuals from Kent and Dorset. Antiquity, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2025.10139