For much of human history, the slow maturation of the human mind has been treated as a given. Children take years to reach adult competence. Adolescents linger in cognitive limbo. Compared with other primates, Homo sapiens spends an unusually long time becoming itself.

This extended developmental arc has often been explained in broad strokes. Bigger brains take longer to wire. Complex societies demand prolonged learning. Culture stretches childhood. All of that remains true. But a new comparative study of human and macaque brains suggests something more precise and more revealing. The delay is not just cultural or behavioral. It is written deep into the cellular choreography of the developing brain.

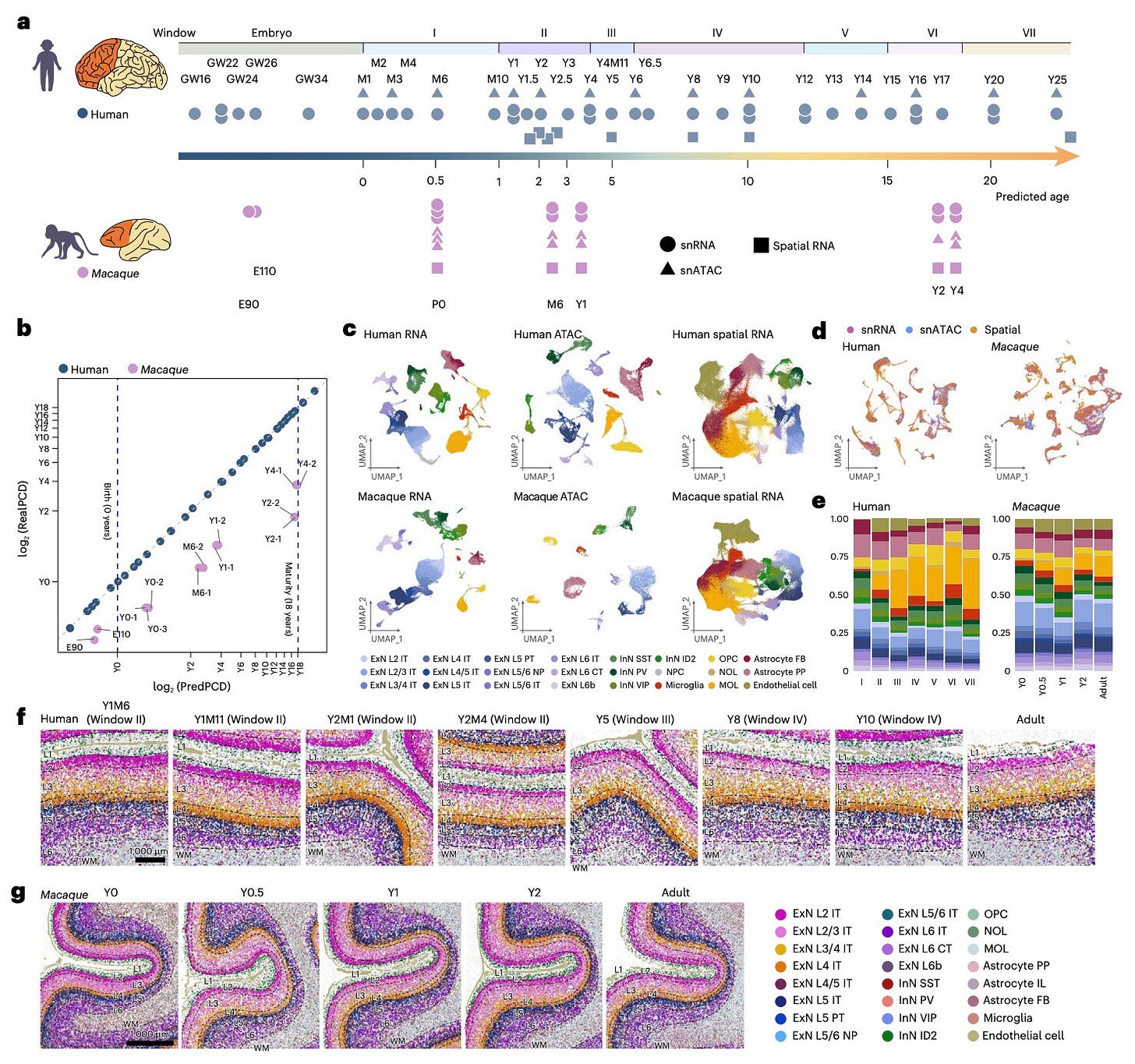

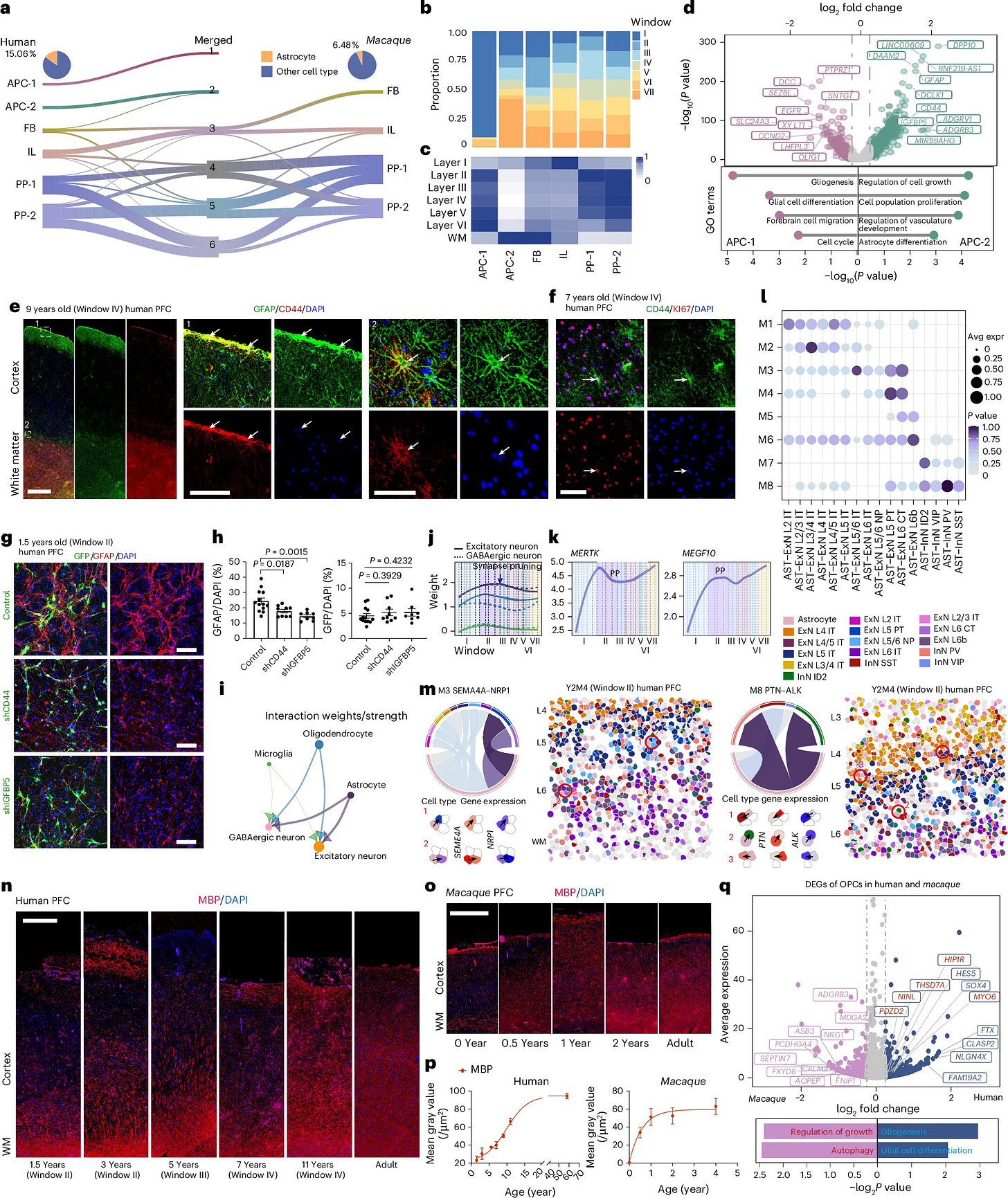

By comparing postnatal brain tissue from humans and macaques at single-cell resolution, researchers have identified1 a distinctive tempo in the maturation of the human prefrontal cortex. The region that supports planning, abstraction, social reasoning, and impulse control does not simply grow larger in humans. It grows slower, cell by cell, pathway by pathway.

The finding reframes a long-standing puzzle in human evolution. Our prolonged childhood may not just support learning. It may be a biological strategy that reshaped how cognition, cooperation, and vulnerability evolved together.