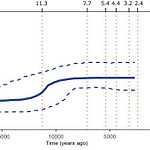

There’s something almost counterintuitive about the idea that dairy came before writing, before cities, before the wheel. And yet the evidence keeps pushing the date further back. The latest comes from the Zagros mountains of Iran, where a team of researchers has found residues of caprine milk products trapped in Neolithic pottery and preserved in the dental plaque of people who died roughly nine millennia ago.

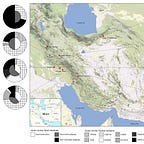

The Zagros range has a particular significance in this story. The archaeological record there already suggests it was one of the earliest centers of goat and sheep domestication. The region sits in what the study’s authors describe as “a cradle for goat domestication and eastward spread of agropastoralism.” Finding dairy residues here, this early, would mean that the relationship between humans and caprine milk wasn’t just incidental to domestication. It was, in some sense, part of the point.

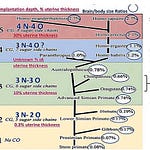

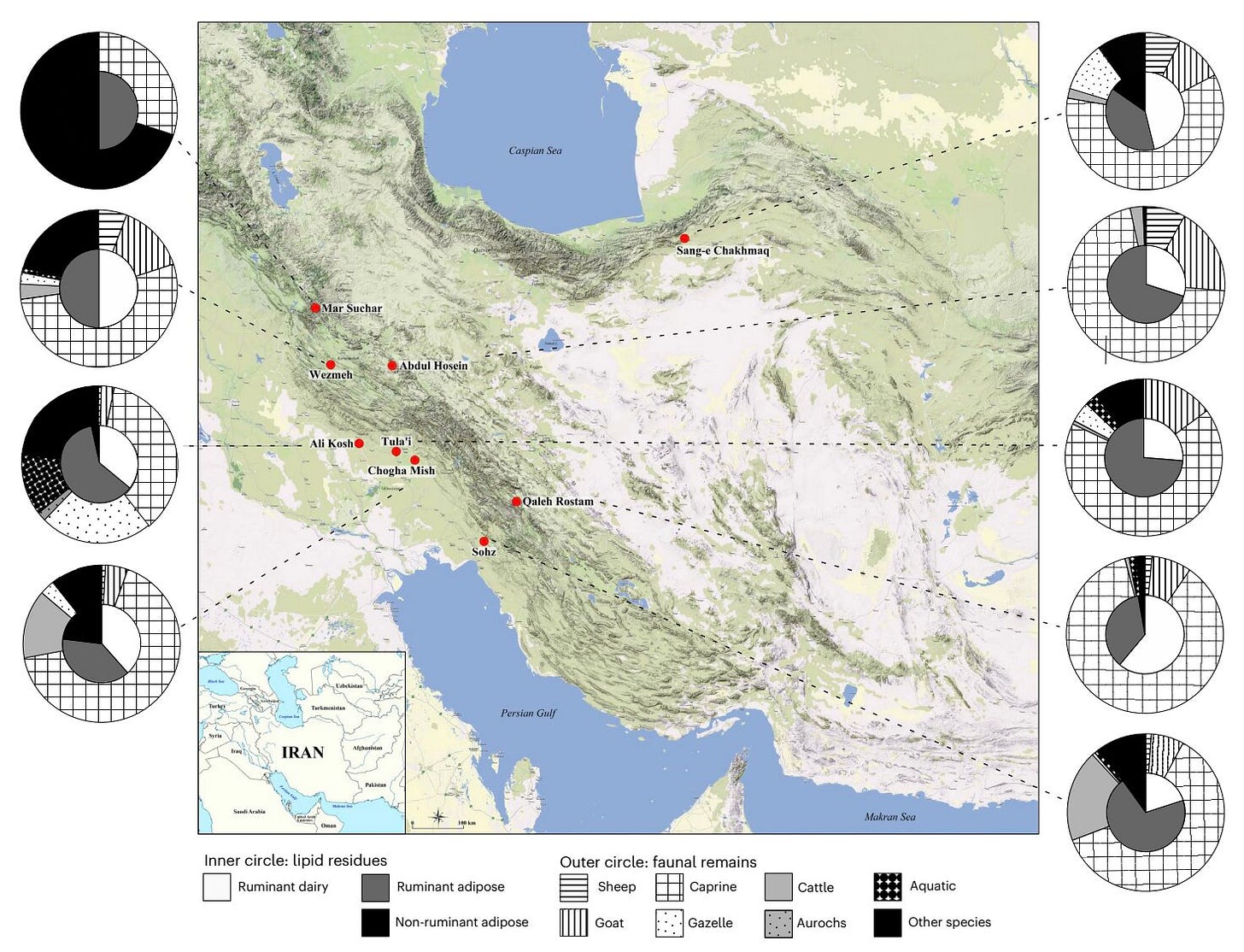

The research team, led by Emmanuelle Casanova, Hossein Davoudi, and colleagues from institutions including the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Université Paris-Saclay, and the University of Tehran, used two independent lines of chemical evidence.1 The first involved lipid analysis: extracting fat molecules from pottery sherds collected at Neolithic sites, looking for the molecular signatures of ruminant milk. The second was rarer and arguably more intimate. They analyzed calcified dental plaque on skeletal remains from the same period and found milk proteins preserved inside it.

That second method deserves a moment’s pause. Dental calculus forms when plaque mineralizes on teeth. It’s porous enough to trap proteins from food and drink, which can then survive for thousands of years in a kind of biological amber. When you find milk proteins in ancient dental calculus, you’re not inferring behavior from indirect proxies. You are reading the diet of a specific individual, written into their teeth.