There’s a particular kind of extinction theory that tends to get overlooked: not the dramatic ones involving volcanoes or invading armies of Homo sapiens, but the slow, biological ones. The kind where a species doesn’t lose a fight so much as it fails, incrementally, to replace itself.

A paper published in early 2026 in the Journal of Reproductive Immunology1 makes a case for exactly this kind of quiet catastrophe. The authors, Pierre-Yves Robillard, S. Saito, and G. Dekker, propose that Homo neanderthalensis may have been disproportionately vulnerable to preeclampsia and eclampsia, two pregnancy complications that, at their worst, can kill both mother and child. If they’re right, then one of the factors behind Neanderthal extinction wasn’t predation or climate or competition. It was childbirth.

To understand why this matters, you have to start with a strange feature of human reproduction that we tend not to think about: the placenta is aggressive.

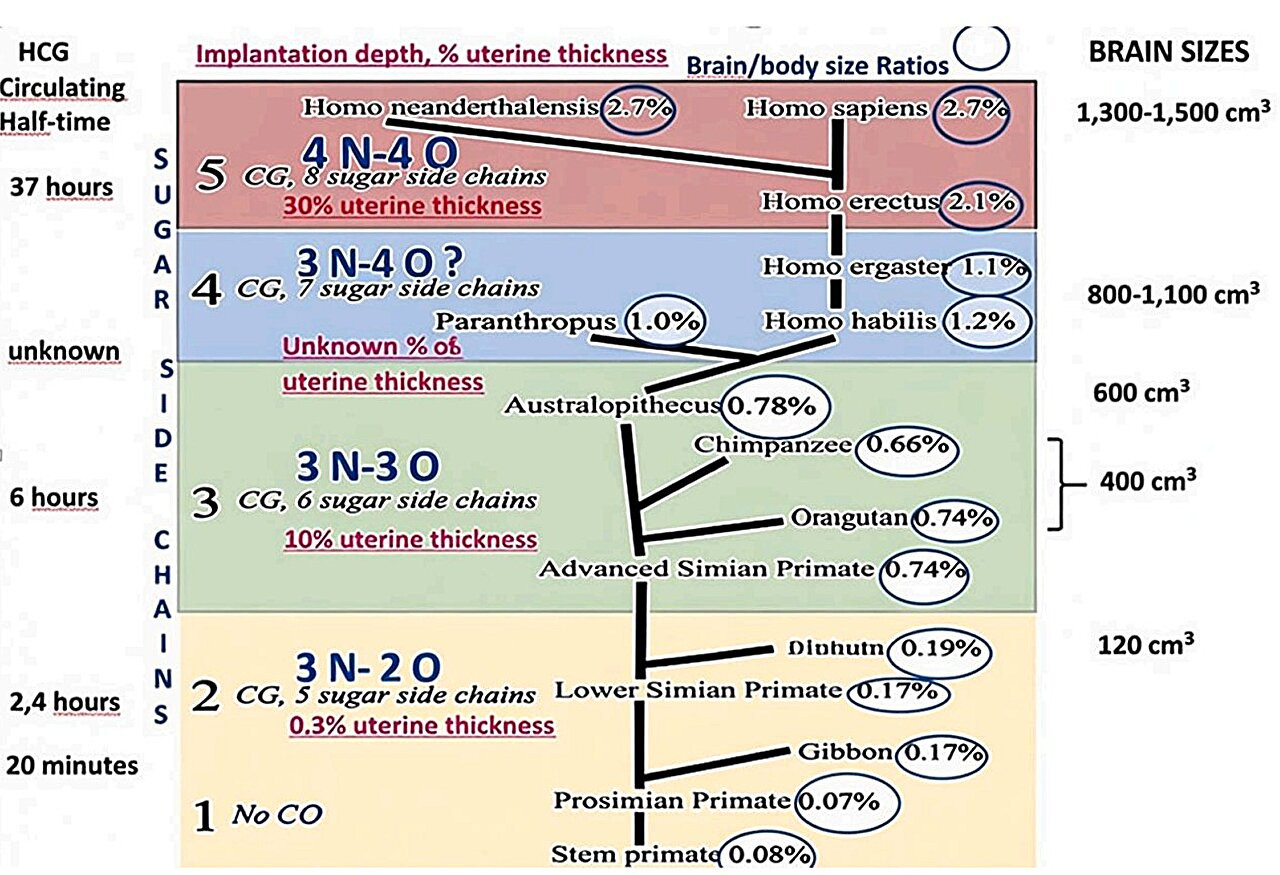

In most mammals, the placenta sits relatively politely against the uterine wall, drawing nutrients without penetrating too deeply. In humans, it’s different. The placenta actively burrows into the uterine lining, remodeling the mother’s spiral arteries to ensure that blood flows freely and constantly to the fetus. This is partly a consequence of how metabolically expensive human brains are, even in utero. The fetus needs a lot of fuel, and the placenta evolved to take what it needs.

But this deep invasion comes with a cost. When it fails, when the placenta can’t implant properly or can’t remodel those arteries, blood flow to the fetus is compromised. The placenta begins shedding microscopic debris into the maternal bloodstream, a kind of biological distress signal. The mother’s immune system reads this and, in some cases, responds by raising blood pressure. That cascade, if it continues, becomes preeclampsia. If it escalates to seizures, it becomes eclampsia. Both can be fatal.

Here’s the part that’s actually strange, though. When the placenta struggles to implant, the mother doesn’t always develop preeclampsia. Quite often, her body ignores the stress signals entirely. The baby may be growth-restricted, but the mother stays healthy. Why this protective dampening exists, and what controls it, isn’t fully understood. What Robillard and colleagues propose is that this dampening mechanism, whatever its molecular basis, may have been absent or deficient in Neanderthal women.