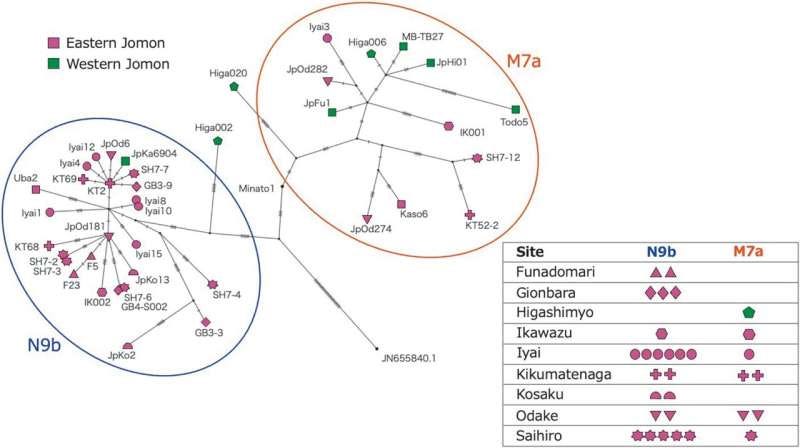

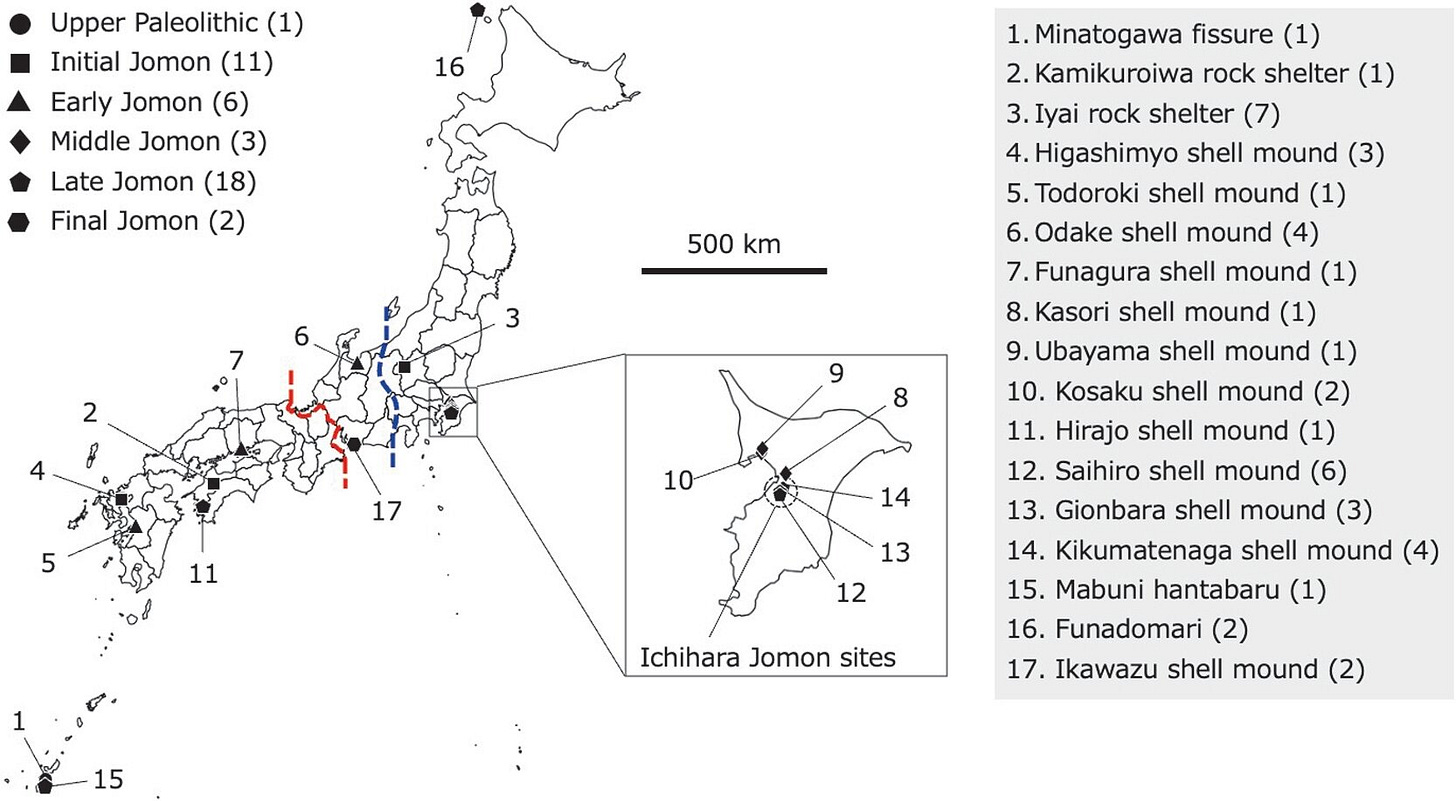

There’s a puzzle at the heart of Jomon genetics that has nagged at researchers for decades. Pull DNA from Jomon skeletons excavated in eastern Japan — Hokkaido, the Kanto region, the shell mounds strung along what is now Chiba Prefecture — and you find haplogroup N9b dominating the mitochondrial lineages. Do the same for western Jomon remains, and M7a takes over. The split is striking enough that it looks, at first glance, like two different peoples.

The standard explanation leaned into exactly that reading. N9b’s closest relatives in the modern world cluster in Northeast Asia, in places like Primorsky Krai along the Pacific coast of Russia. M7a’s relatives are mostly found further south, in Southeast Asia and southern China. So the argument went: two separate ancestral populations, arriving from two different directions, their descendants settling opposite ends of the archipelago. The haplogroup map, on this view, was a fossil record of two founding migrations.

The problem is that this interpretation rests heavily on patterns in living populations. Present-day genetics reflects tens of thousands of years of migration, admixture, and drift. Inferring ancient movements from modern distributions is a bit like trying to reconstruct medieval trade routes from what you find in contemporary supermarkets. The signal is there, but it’s noisy and easily misleading.

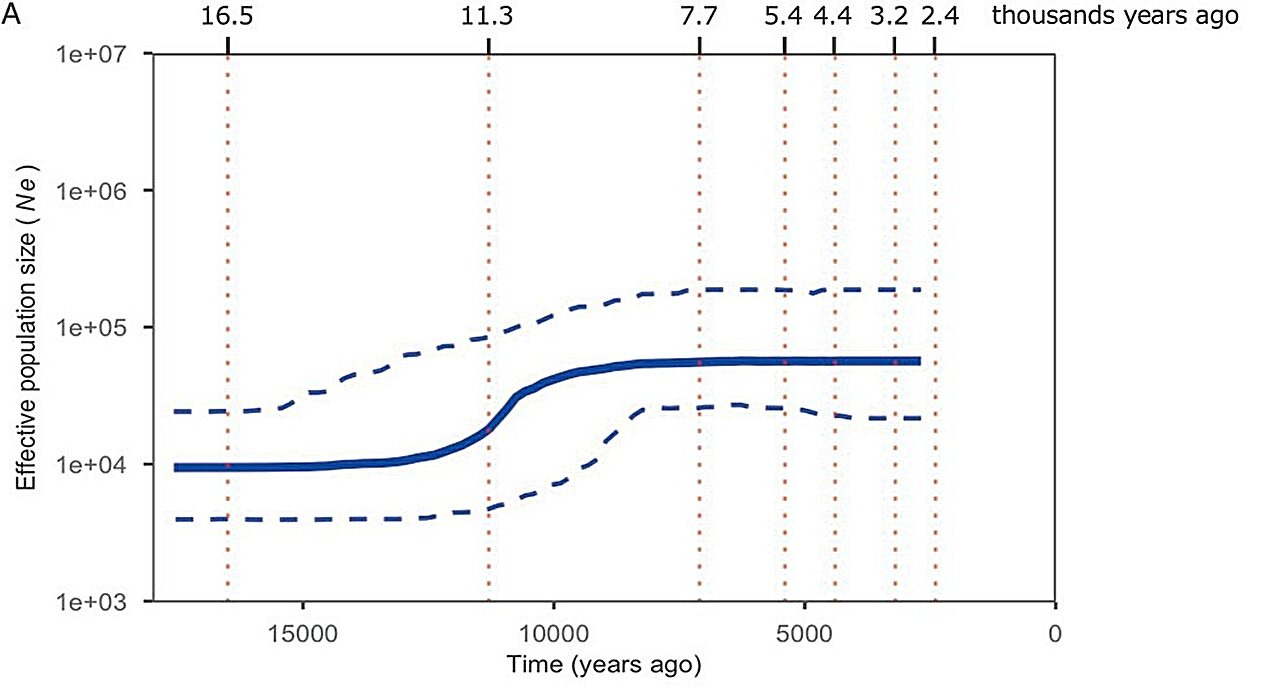

A study published in early 2026 in Anthropological Science1 offers a different picture. The team, led by researchers at the University of Tokyo, sequenced complete mitochondrial genomes from 13 newly analyzed Jomon individuals excavated from three shell mound sites in Ichihara City, Chiba Prefecture. Combined with previously published data, they assembled a dataset of 40 whole mitogenome sequences spanning the Initial through Final phases of the Jomon period. Then they ran simulations to ask a pointed question:

Does the east-west haplogroup split actually require two founding populations?

Or could drift alone, starting from a single ancestral group, produce what we see?

The answer turns out to be yes — under the right conditions, drift is sufficient. But the conditions matter, and they tell us something real about how the Jomon were structured.