The cave opens as a crack in the limestone, barely wide enough to squeeze through. Inside, the main chamber is modest. Three and a half meters long, one and a half wide, with a ceiling you could touch if you stood on someone’s shoulders. But on the east side, the chamber develops into something else: a vertical shaft that climbs five meters straight up to the surface.

That shaft is where they put the bodies.

When Martin Stables began excavating Heaning Wood Bone Cave in 2016, he knew the site had given up human remains before. Cavers had poked around in the 1950s and 1970s, pulling out bones and a few artifacts. But the recent excavations revealed something more structured than anyone expected.1 The remains weren’t scattered debris from occasional use. They represented a pattern. People had been deliberately lowering bodies down that vertical shaft for thousands of years.

Seven thousand years, to be precise.

Radiocarbon dating organized the dead into three distinct clusters. The earliest individual lived between 9290 and 8925 BC, during the Early Mesolithic. Four more people date to the Early Neolithic, between 3760 and 3520 BC. Two final individuals belong to the Early Bronze Age, around 2195 to 2025 BC. Same cave. Same vertical entrance. Three episodes of burial separated by millennia of apparent silence.

The earliest burial is a child. Genomic analysis pulled from fragmentary bone confirmed she was female, probably between two and a half and three and a half years old when she died. She’s now the oldest known human burial in northern Britain. Stables, a self-taught archaeologist from the nearby village of Great Urswick, named her the “Ossick Lass.” Ossick is how locals pronounce Urswick. The term “lass” marks geographic origin, like saying “she’s Joe’s lass” or “she’s a good lass.” It means: she’s from here.

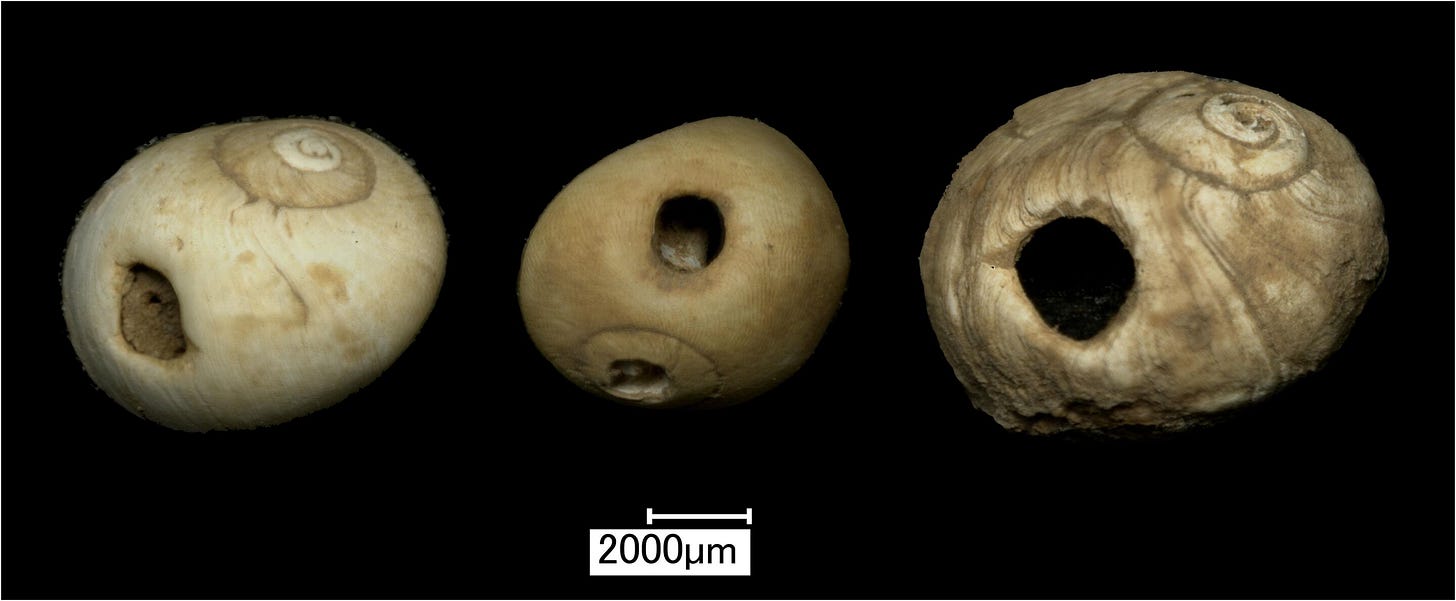

Five perforated periwinkle shells were found in the cave deposits. One of them radiocarbon dates to the same period as the child. The shells are so small and fragile that what survives is almost certainly a fraction of what was originally there. But their presence strengthens the argument that this was a prepared burial, not an accidental death in the cave. Someone placed her there, probably with ornaments.

Her isotope values are unusual compared to the later burials. She shows elevated carbon-13 and nitrogen-15, which could mean two things. Either she was still breastfeeding when she died, which leaves a chemical signature, or she was eating more marine food than the others. If it’s the latter, her radiocarbon date might be slightly too old. Marine organisms incorporate older carbon from the ocean, which throws off the calibration. Either way, she represents the earliest secure evidence of deliberate Mesolithic burial this far north in Britain.