The Selfish Origin of Sharing: What Hadza Hunter-Gatherers Reveal About Human Egalitarianism

When anthropologists gave the Hadza the choice to give or take, most chose to take. What does this tell us about the evolutionary roots of fairness?

Picture a research team sitting in a Tanzanian camp with 117 Hadza people, one at a time, asking them to redistribute food. The Hadza are hunter-gatherers. They share meat widely. Everyone in anthropology knows this. When a hunter brings back game, it gets divided up. Not just to family, but across the whole camp. This is the stuff of textbooks, the evidence we point to when we want to say something about human nature and cooperation.

But here’s what happened in the experiment.1

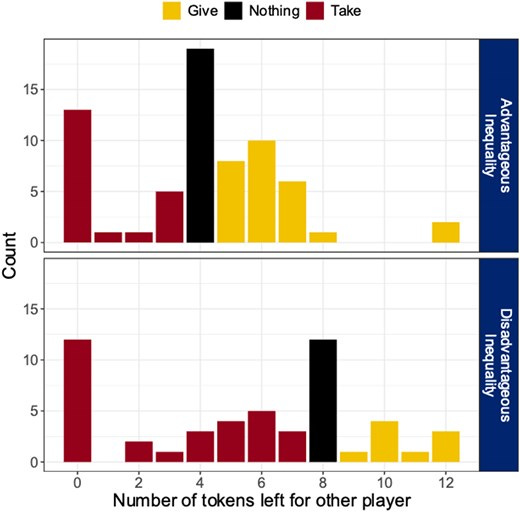

The researchers laid out photographs. One showed the participant. The other, face down, showed a campmate. Then they placed tokens on the photos, each token worth a dried banana chip. Sometimes the participant got eight tokens and the campmate got four. Sometimes it was reversed. The rule was simple: move the tokens however you want. Give some away. Take some. Do nothing. Your choice.

Most people took.

When participants started with more than their campmate, only 40.9% gave anything at all. A full 30% took even more, making the gap worse. The most common outcome across both conditions was taking everything. Twelve tokens for me, zero for you.

When participants started with less, they took more readily. That makes sense. But even here, most didn’t stop at equality. Of those who took, 73% took more than necessary to even things out. Forty percent took it all.

This creates a problem. The Hadza really do share food. Studies from the 1980s showed that meat from large game gets distributed so widely that hunters receive no preferential share of their own kills. More recent data suggests hunters now keep more, but they still give away about 58% of large game to people outside their household. The sharing is real. But the private preferences measured in this experiment don’t match the public outcomes. Something else must be driving the redistribution.