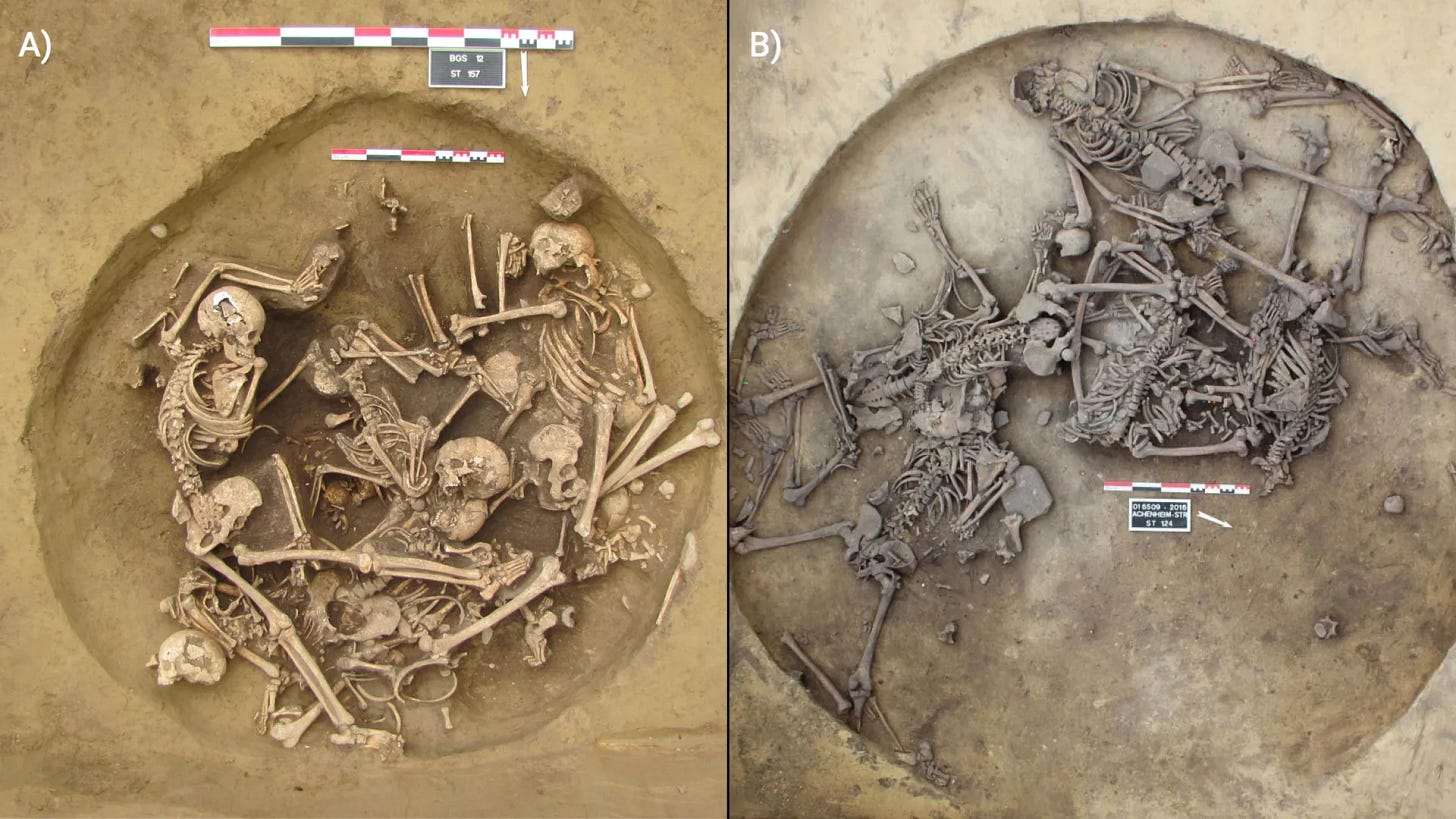

Two circular pits in northeastern France held something archaeologists had never quite seen before.1

The first pit, at a site called Achenheim, contained six bodies showing signs of brutal violence. Multiple unhealed skull fractures. Broken bones that never had time to mend. The kind of damage that signals death came quickly, and with deliberate excess. Scattered among these bodies were four severed left upper limbs, cut cleanly through the humerus and deposited without the rest of their skeletons.

The second pit, at Bergheim about 20 kilometers away, told a similar story. Eight bodies bearing the marks of extreme force. Seven more isolated left arms, again severed and placed separately.

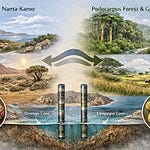

The dates clustered tightly around 4300 to 4150 BCE, during the late Middle Neolithic. This was a period of upheaval in the Upper Rhine Valley, when local Bruebach-Oberbergen communities were being rapidly displaced by incoming western Bischheim groups from the Paris Basin. Fortifications appeared. Settlements grew larger and more aggregated. And the bones started showing up with trauma.

But the combination of complete skeletons subjected to overkill and carefully removed left upper limbs stood apart from other Neolithic violence. The pattern didn’t fit massacres, where entire communities were wiped out. It didn’t match executions of captured raiders. Something else was happening here.

Teresa Fernández-Crespo and her colleagues wanted to know who these people were. Not just in the abstract, but specifically: Where did they come from? What did they eat? How did they move through the landscape? Were the severed arms and the brutalized bodies connected, or did they represent different events, different enemies, different meanings?

The answers came from chemistry.