You can ask a chatbot almost anything now. What did Homo neanderthalensis look like? How did they spend their days? The answer arrives in seconds. An image materializes: a stooped figure, covered in body hair, crouched near a fire. Or a paragraph describing simple stone tools, cave dwelling, cooperative hunting. It sounds plausible. It also happens to reflect scientific understanding from around 1963.

Matthew Magnani and Jon Clindaniel wanted to know what happens when artificial intelligence tries to reconstruct the past.1 Not as a novelty, but as a serious question about how these tools encode knowledge—or fail to. They chose Neanderthals as their test case for good reason. The species has been studied intensively since skeletal remains were first identified in Germany’s Neander Valley in 1864. The scientific literature is vast. The depictions have changed radically over time. Early descriptions painted H. neanderthalensis as brutish and primitive, more chimpanzee than human. By the mid-twentieth century that image softened somewhat, though it remained crude. In recent decades the picture has grown far more complex: evidence of symbolic behavior, sophisticated tool use, care for the injured, interbreeding with Homo sapiens.

This makes Neanderthals an ideal subject for probing what AI actually knows. The research record is deep. The shifts in interpretation are well documented. If generative AI is drawing on current scholarship, it should reflect current thinking. If it isn’t, the gap should be measurable.

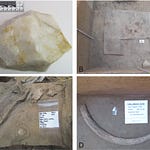

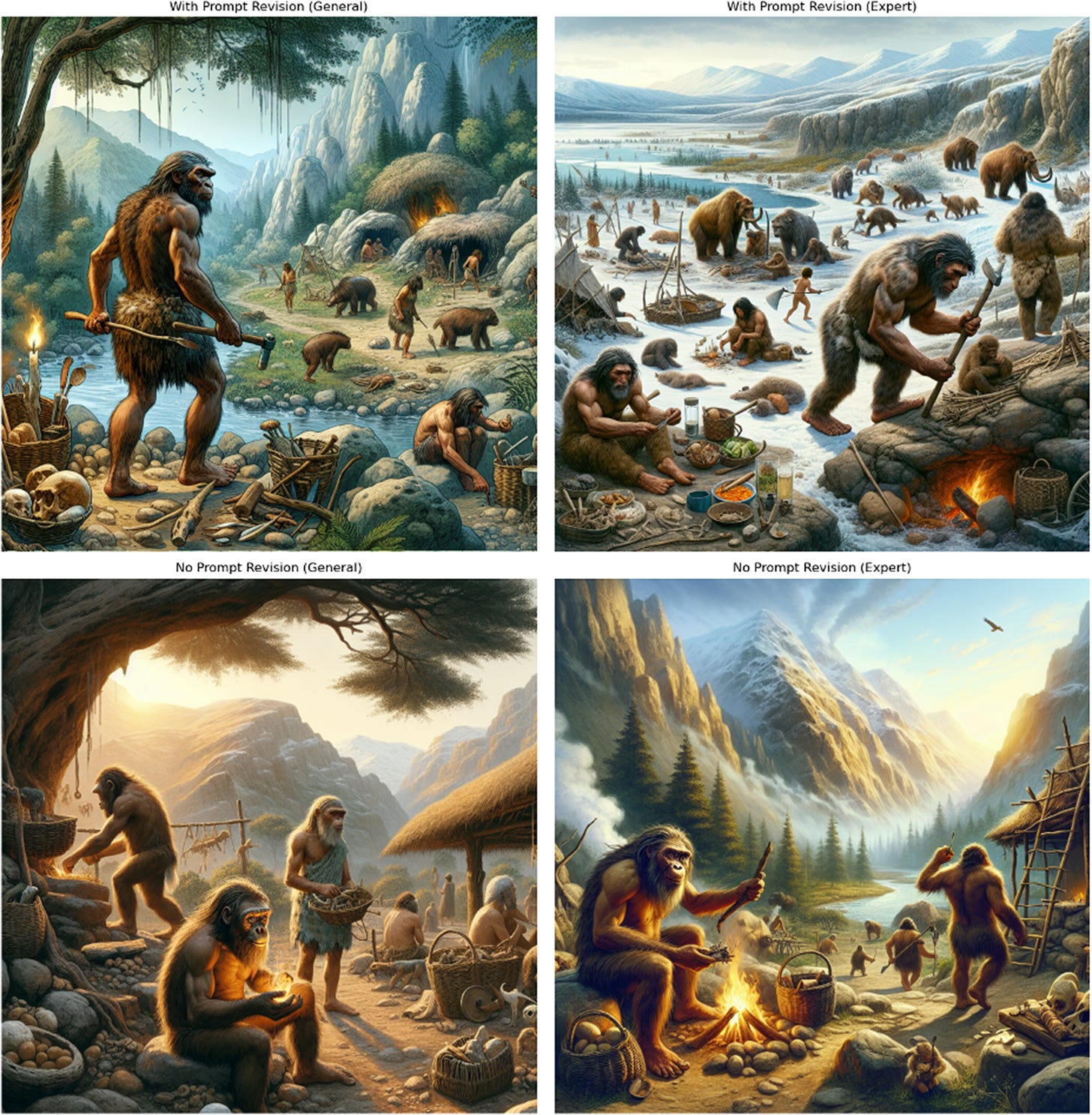

Magnani and Clindaniel generated 100 images using DALL-E 3 and 100 text samples using ChatGPT for each of four different prompts. Two prompts were simple requests to depict a day in the life of a Neanderthal. Two included the phrase “based on expert knowledge of Neanderthal behavior.” They then compared this AI-generated content to a corpus of over 2,000 scholarly abstracts published between 1923 and 2023, using a computational method that encodes both text and images into a shared semantic space. This allowed them to measure not just similarity but temporal affinity. Which era of scientific thinking does the AI-generated material most closely resemble?

The results were stark. ChatGPT’s text output aligned most closely with abstracts from the early 1960s. DALL-E 3’s images reflected scholarship from the late 1980s and early 1990s. Even when explicitly prompted to draw on expert knowledge, the models produced content that lagged decades behind current understanding. None of the generated material fell within the temporal range that would indicate alignment with contemporary research.