There are four ceramic jars in the Museum August Kestner in Hanover, Germany. They belonged to a woman named Senetnay, who lived around 1450 BCE and served as wet nurse to the future Pharaoh Amenhotep II. When she died, her internal organs were removed, embalmed, and placed inside these jars. The practice was standard for elite burials in ancient Egypt. The organs were preserved with complex balms, often enriched with fragrant and resinous substances, because the Egyptians believed they would be needed in the afterlife.

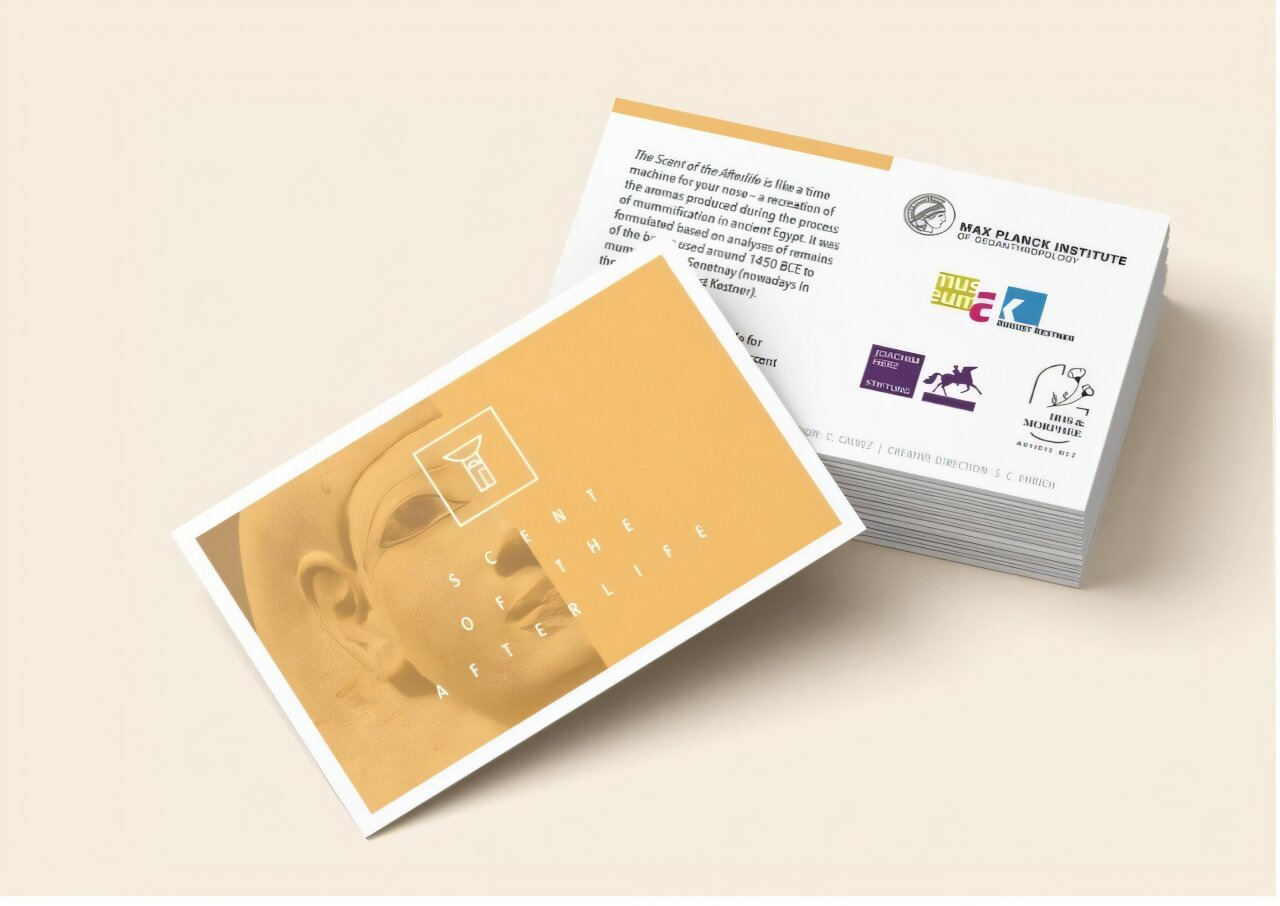

The jars sat in the museum for decades. Then, in 2023, a team led by Barbara Huber at the Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology analyzed residues that remained inside two of them. They used biomolecular techniques to identify the aromatic ingredients in the embalming recipe. That work was published in Nature Scientific Reports.1 But the team did something unusual with the results. Instead of stopping at a journal article, they collaborated with a perfumer to recreate the scent and brought it into museums where visitors could smell it.

The result is a case study2 in how scientific data can be transformed into something tactile and sensory. The process involved archaeologists, chemists, curators, a perfumer, and an olfactory heritage consultant. What they produced is not a museum label or a digital reconstruction. It is a smell. Visitors can lift a lid, lean in, and inhale something that approximates what filled the air during an embalming ritual 3,500 years ago.

This is not a gimmick. It is a carefully constructed interpretation of biomolecular evidence, and it raises real questions about how museums engage with the past.