For much of the twentieth century, the story of the first Americans began with Clovis. Finely fluted spear points appeared across North America around 13,000 years ago, seemingly out of nowhere, and archaeologists treated them as a cultural starting gun. Alaska, by contrast, often played the role of a cold corridor rather than a creative landscape.

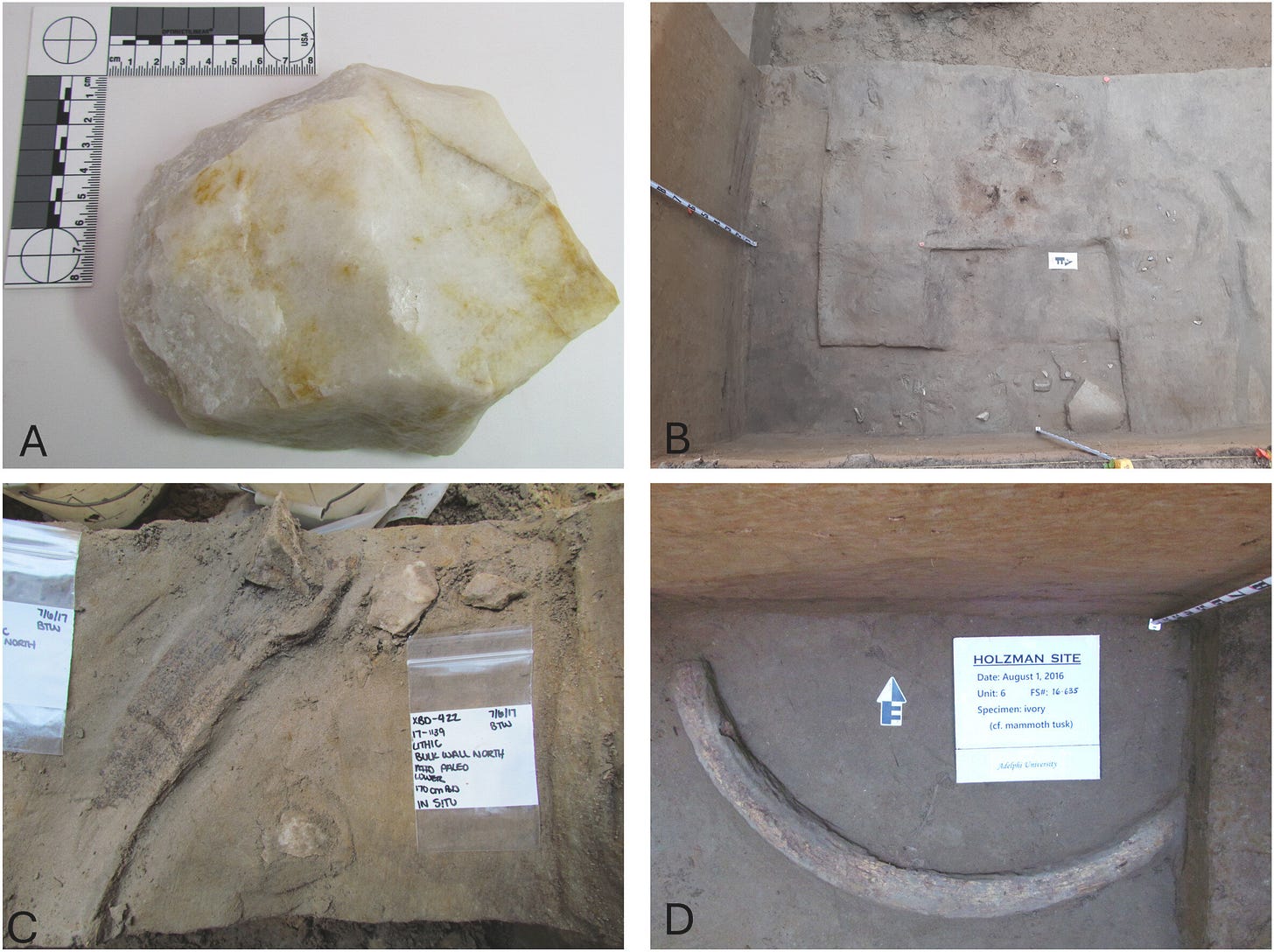

That picture is now harder to sustain. Evidence from the middle Tanana Valley,1 deep in Alaska’s interior, points to a population of Late Pleistocene hunter-gatherers experimenting with stone and mammoth ivory technologies well before Clovis entered the archaeological record. These people were not simply passing through. They were making tools, circulating materials, and refining techniques that would later echo across the continent.