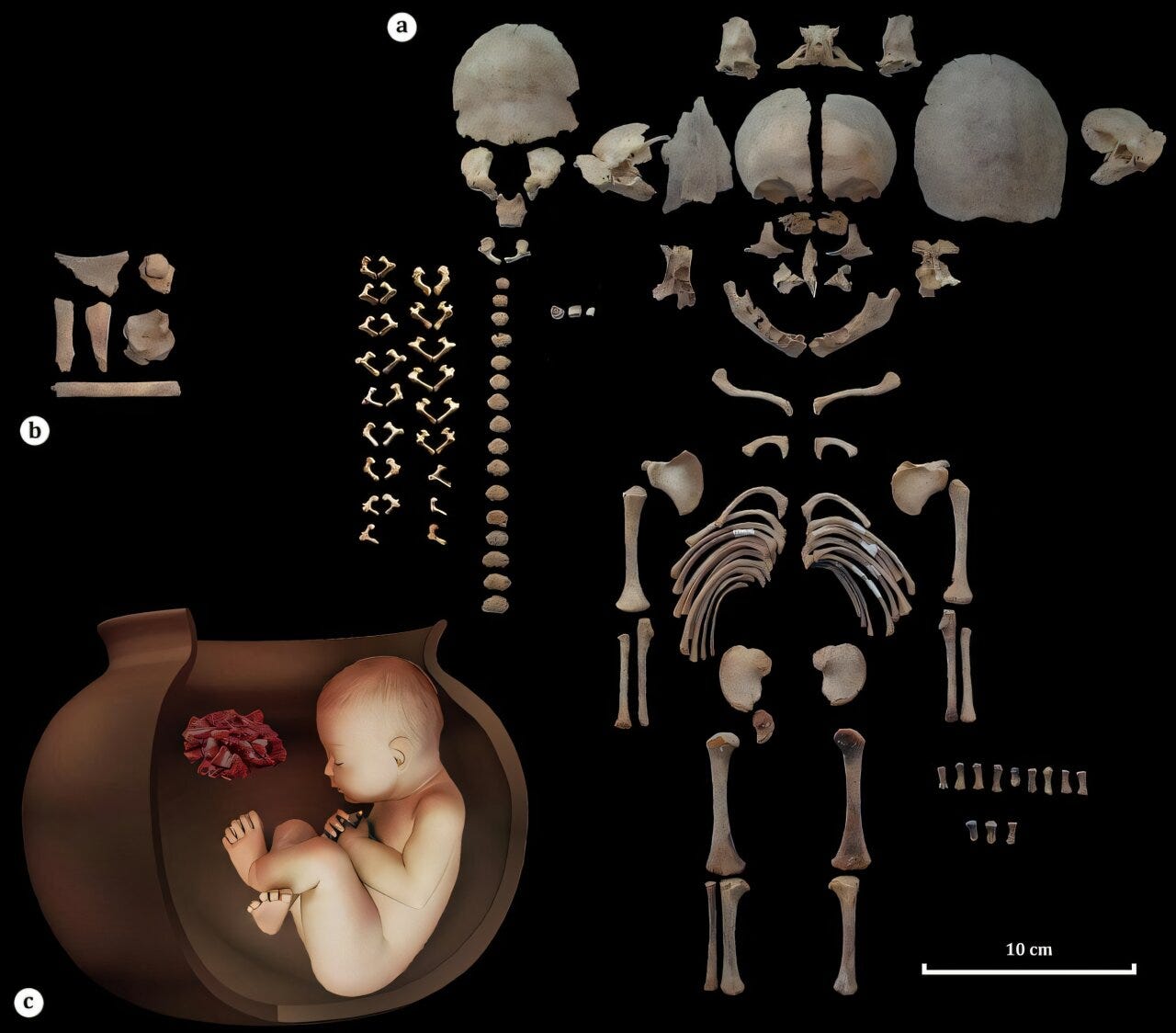

In the middle of a prehistoric settlement in northwestern Iran, two unborn children were laid to rest inside clay vessels. The burials were separated by only a few meters and likely by little time. Yet almost everything else about them was different.

One fetus was carefully placed inside a reused cooking pot, accompanied by animal bones and a worked stone. The other was sealed into a vessel with no offerings at all, tucked away in what may have been a storage space. Both date to roughly 6,500 years ago, during the mid fifth millennium BCE. Together, they offer a rare and intimate glimpse into how prehistoric communities grappled with pregnancy loss, personhood, and memory.

A new study from Chaparabad, published in Archaeological Research in Asia,1 does not claim to solve these questions. Instead, it shows how little we should expect a single answer.