Deep-sea sediment cores don’t seem like the place to look for answers about human behavior. But two cylinders of mud pulled from the ocean floor off southern Africa have turned out to hold something more valuable than anyone expected: a continuous record of what the landscape looked like between 180,000 and 30,000 years ago.

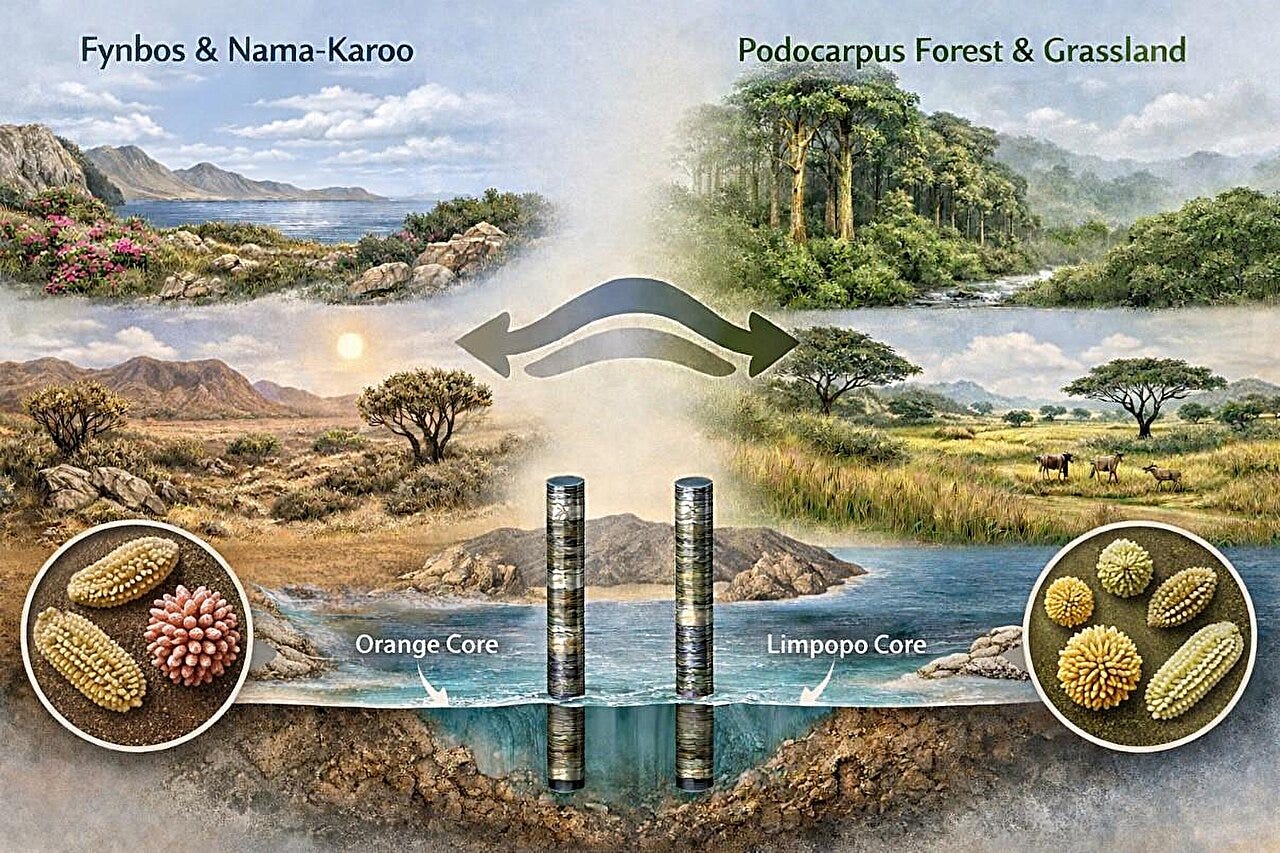

One core came from the eastern margin, near the mouth of the Limpopo River. The other from the west, off the Orange River basin. Together, they capture pollen grains washed out to sea over tens of thousands of years. The grains settled into the mud in layers, preserving a timeline of which plants were growing when, and by extension, what the climate was doing.

This matters because southern Africa during the Middle Stone Age was not one environment. It was a patchwork. Winter rains fell in the west. Summer rains in the east. Fynbos shrublands dominated some areas, Afromontane forests others, grasslands and semi-desert elsewhere. The question has always been whether you could even construct a regional climate story given all that variation. Terrestrial records, pulled from caves and rock shelters, tend to reflect local conditions, predator behavior, or the quirks of preservation. Marine cores, by contrast, integrate signals across entire river basins. They smooth out the noise.

What Sara García-Morato and her colleagues found1 in those cores was coherent. During glacial periods, southern Africa got wetter. Forests expanded in the east. Fynbos thickened in the west. During warm interglacials, the opposite happened. Grasses spread. Rainfall dropped. The pattern held across both margins, which suggests it wasn’t just a local fluke.

This is useful on its own. But the real payoff comes when you line up that environmental record with the archaeological one.

Two cultural traditions dominate the late Middle Stone Age in southern Africa. The Still Bay, which appears around 76,000 years ago, is known for finely worked bifacial stone points, engraved ochre, bone tools, and shell beads. It shows up at coastal sites like Blombos Cave and Sibudu. Then, after a gap of a few thousand years, the Howiesons Poort emerges around 64,000 years ago. It’s defined by backed microliths, standardized blade production, and what may be early evidence for bow-and-arrow technology. The Howiesons Poort is geographically broader, appearing not just on the coast but inland.

For years, the assumption has been that climate drove these changes. That makes intuitive sense. Resources contract, people move, new technologies emerge. But when you actually match the dates to the vegetation record, the story falls apart.