The Problem With Paleolithic Art That’s Less Than a Millimeter Deep

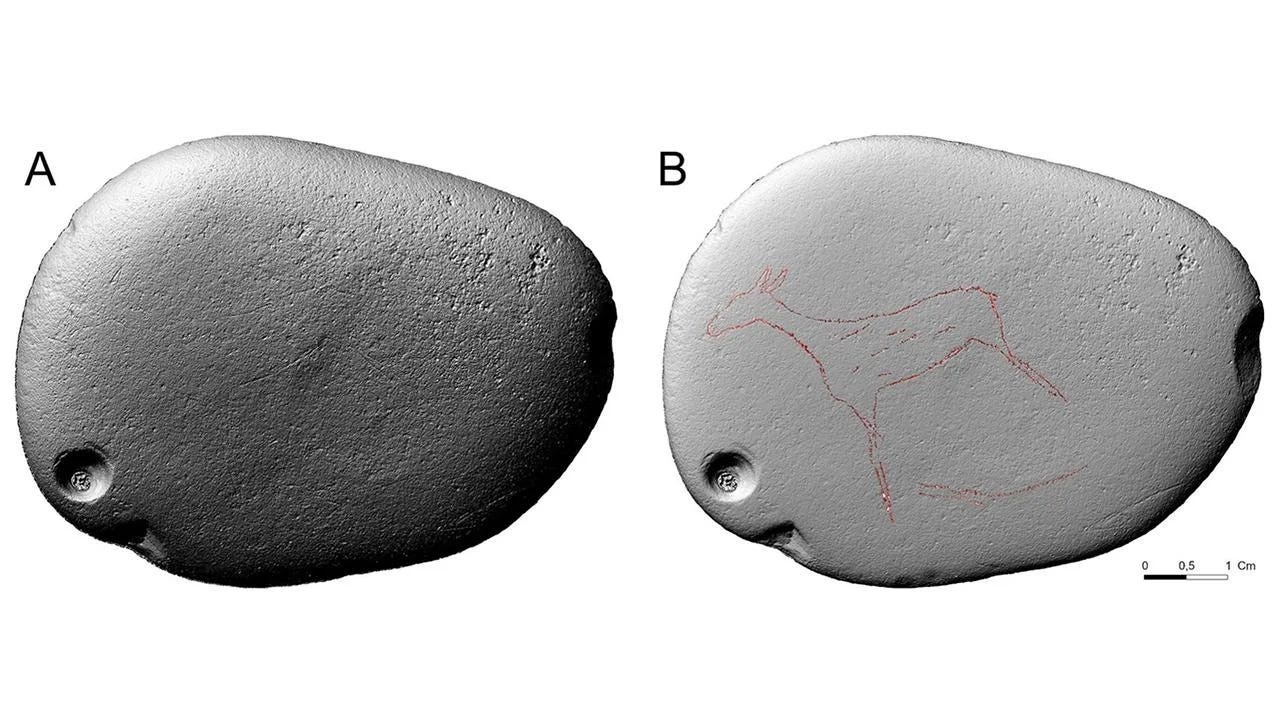

A new digital method reveals what’s really carved on Late Paleolithic stone tools, and what’s just rock.

Someone once drew a human head on a piece of Late Paleolithic portable art from Cova Matutano. The tracing made it into publications. Other researchers cited it. The head became part of how we understood the visual repertoire of Final Paleolithic communities in eastern Spain, roughly 12,000 to 10,000 years ago.

It wasn’t a head. It was stone.

The engravings from this period sit at the edge of what human eyes can reliably parse. Most grooves measure less than a millimeter deep. Time has not been kind. Erosion softens edges. Mineral deposits fill cracks. The rock itself has texture, natural fissures, variations in grain. When you’re trying to identify a deliberate cut made by a person using a sharp edge 12,000 years ago, you’re working in a space where geology and archaeology blur into each other.

A team from Universitat Jaume I, the University of Barcelona, and ICREA wanted to know if digital methods could do better than the human eye. Their study, published in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports,1 focused on three engraved objects from Cova Matutano. The site sits in eastern Spain and has long served as a reference point for understanding Final Paleolithic imagery across the Iberian Mediterranean.

The problem is simple to state and difficult to solve. An engraving less than a millimeter deep looks like almost nothing. Hold the stone at the wrong angle and the mark disappears. Tilt it another way and a natural crack starts to look purposeful. Earlier work relied on direct observation. Archaeologists studied the pieces under light, made drawings, published tracings. Those tracings carried the weight of interpretation baked in. If you see a curve as part of an animal and I see it as geology, our drawings won’t match. And once a drawing enters the literature, it takes on a life of its own.