There’s a pattern in archaeology where certain places get described as unique, spiritually distinct, somehow set apart from everywhere else. The lower Lahontan drainage basin in western Nevada has been cast in this role. For over a decade, researchers have argued that the people who lived there practiced something no one else in the Intermountain West did: they buried their dead in caves, consistently, for more than 10,000 years. This wasn’t just a matter of convenience or practicality. The practice was interpreted as evidence that the basin itself held special meaning, that it was “a uniquely spiritual space, rather than just some place to live.”

David Madsen, Bryan Hockett, Darrel Cruz, and Ronald Rood weren’t convinced. Their response, published in American Antiquity,1 is both methodical and pointed. They looked at the Bonneville basin in western Utah, the other major lake basin in the Great Basin, and asked a simple question: are cave burials actually rare outside the Lahontan basin? The answer is no. Not even close.

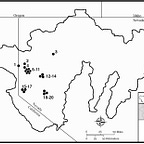

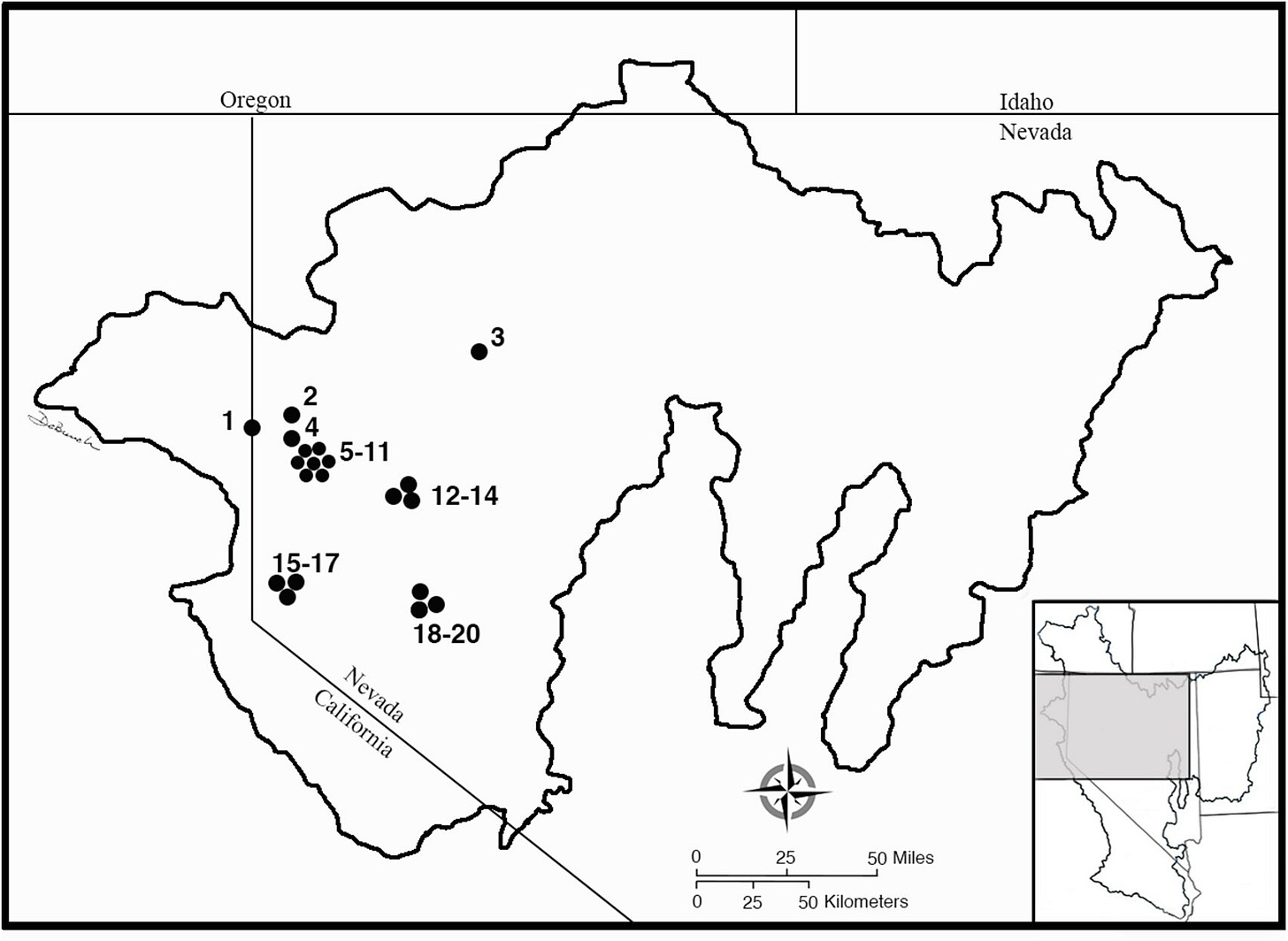

The Bonneville basin contains at least 18 cave and rockshelter sites with burials, holding a minimum of 91 individuals. The real number is almost certainly higher, given that many sites have been vandalized, partially excavated, or not excavated at all. Add five more sites in the upper Lahontan drainage, within range of Bonneville foragers, and the picture shifts. Cave burials weren’t unique to the lower Lahontan basin. They were a widespread practice across the Great Basin, stretching back to the Terminal Pleistocene.

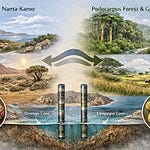

The dates tell the story. The oldest directly dated burial in the Bonneville basin comes from Deadman Cave, at roughly 10,750 years ago. That’s around the same age as the Spirit Cave burial in the Lahontan basin, often cited as one of the earliest in the region. From that point forward, people in both basins buried their dead in caves intermittently for thousands of years. The practice continued through the Archaic period, into the Fremont agricultural interval, and right up to the Late Prehistoric. This wasn’t a flash of ritual innovation. It was a long, sustained tradition.