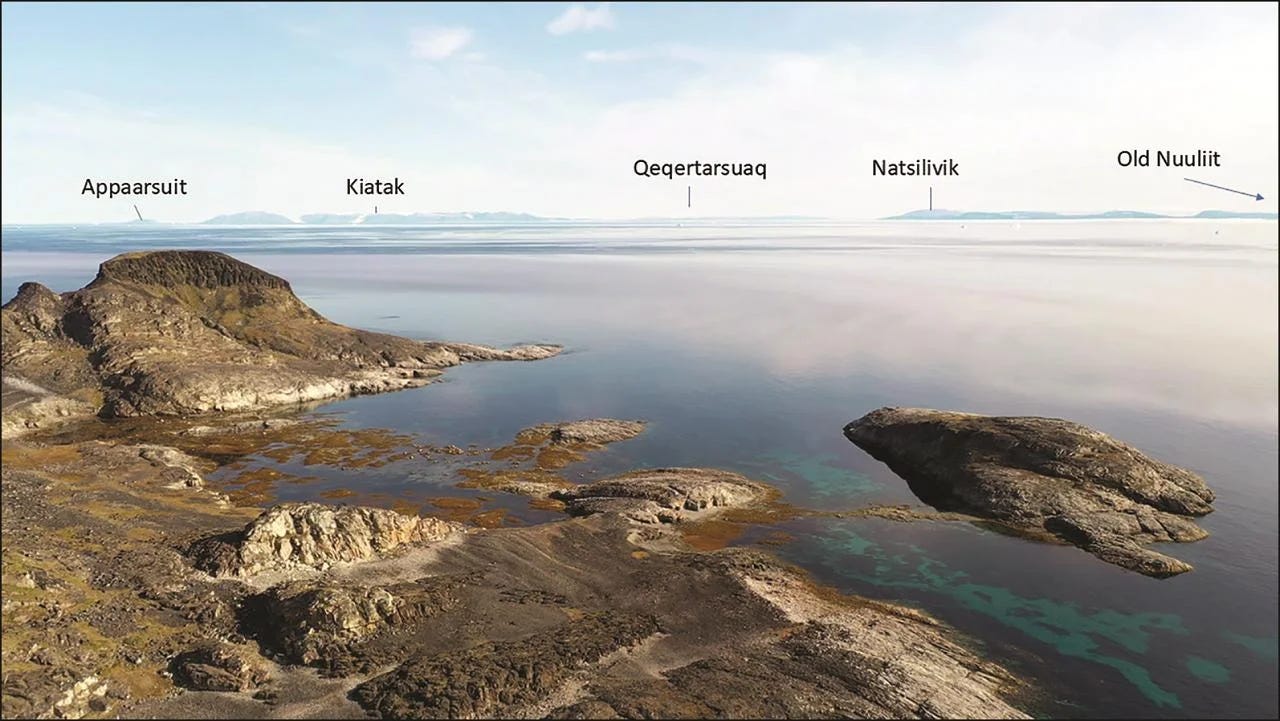

Fifty-two kilometers. That’s the minimum distance between the Greenland mainland and Kitsissut, a cluster of low islands sitting in the middle of Pikialasorsuaq, the largest polynya in the High Arctic. A polynya is where ocean stays open even when everything else freezes. Wind, current, and upwelling heat keep a corridor of water ice-free year round.

The crossing is dangerous now, with powered boats and weather reports. The water is deep—900 meters in places—and two major currents collide there. Cold Arctic water pushes south through Nares Strait while warmer water flows north from Baffin Bay. The mixing creates unpredictable conditions. Fog rolls in. Wind shifts. You can leave in calm weather and find yourself in heavy seas an hour later.

People made this crossing 4,500 years ago in skin boats.

They didn’t do it once. Archaeological survey work1 by a team from the University of Calgary and the University of Greenland found 297 features across the Kitsissut islands, including 15 Early Paleo-Inuit dwelling structures concentrated below seabird nesting cliffs. The tent rings are distinctive. They have axial features—stone alignments that bisect the interior, often with a central hearth. This architectural pattern appears at Early Paleo-Inuit sites across the eastern Arctic, associated with groups archaeologists call Independence I and Saqqaq, though these labels may not represent distinct populations in this region.

A seabird bone from one of the tent rings returned a radiocarbon date between 4,400 and 3,938 calibrated years before present. Seabird bones are tricky to date because marine organisms can make them appear older than they are, but even with cautious calibration, the date confirms Early Paleo-Inuit occupation. The bone came from Uria lomvia, thick-billed murre. Thousands nest on Kitsissut’s cliffs each spring and summer. The Inughuit word is Appat.

The presence of Appat bone matters because these birds are only accessible during the warm season, when the ocean is open. There’s no winter access to Kitsissut. The islands sit where ocean depth and current prevent sea ice from forming stable sheets. Even when ice forms at the edges, the center stays liquid. You can’t walk there. You go by boat or you don’t go at all.

Early Paleo-Inuit communities went. Repeatedly. With families and gear and supplies for multi-day stays. They butchered animals, maintained hearths, and returned across the same 50 kilometers of open water. The tent rings aren’t scattered randomly—they cluster near resource zones, positioned to access seabird colonies and the marine mammals that congregate around polynyas. This wasn’t accidental presence. It was planned, skilled, dangerous travel undertaken for specific purposes.