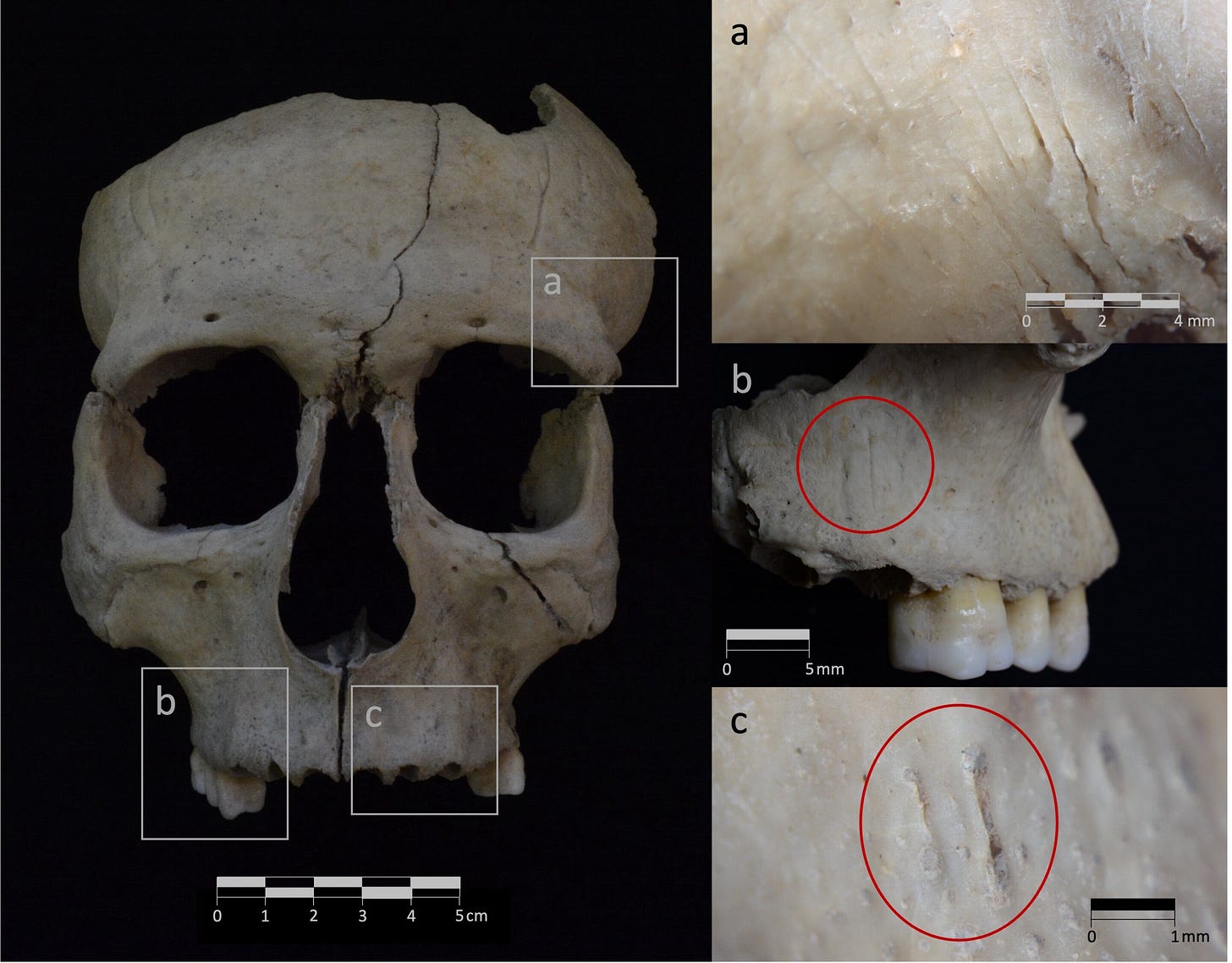

The young man died violently. Someone struck him from behind with a sharp, heavy weapon, the blade cutting deep into the left side of his frontal bone. The angle was nearly perpendicular. Then came more blows to the right side, these at a sharper angle, the cuts overlapping as if the attacker was adjusting their aim. After he fell, someone took a thin instrument and carefully scraped the flesh from his skull, working the blade across the forehead, around the eye sockets, and down over the cheekbones and jaw.

Then they treated the head with resin.

The skull fragments from Olèrdola, a fortified Iberian settlement perched on a limestone outcrop 50 kilometers south of modern Barcelona, sat in storage for years before anyone realized what they represented. When archaeologists finally excavated the interior of a defensive tower in 2022, they found five pieces of cranium scattered across a small area near a stone bench. The tower had burned at the end of the 3rd century BCE. Whatever had been stored there, including this skull, had come to rest in the debris.

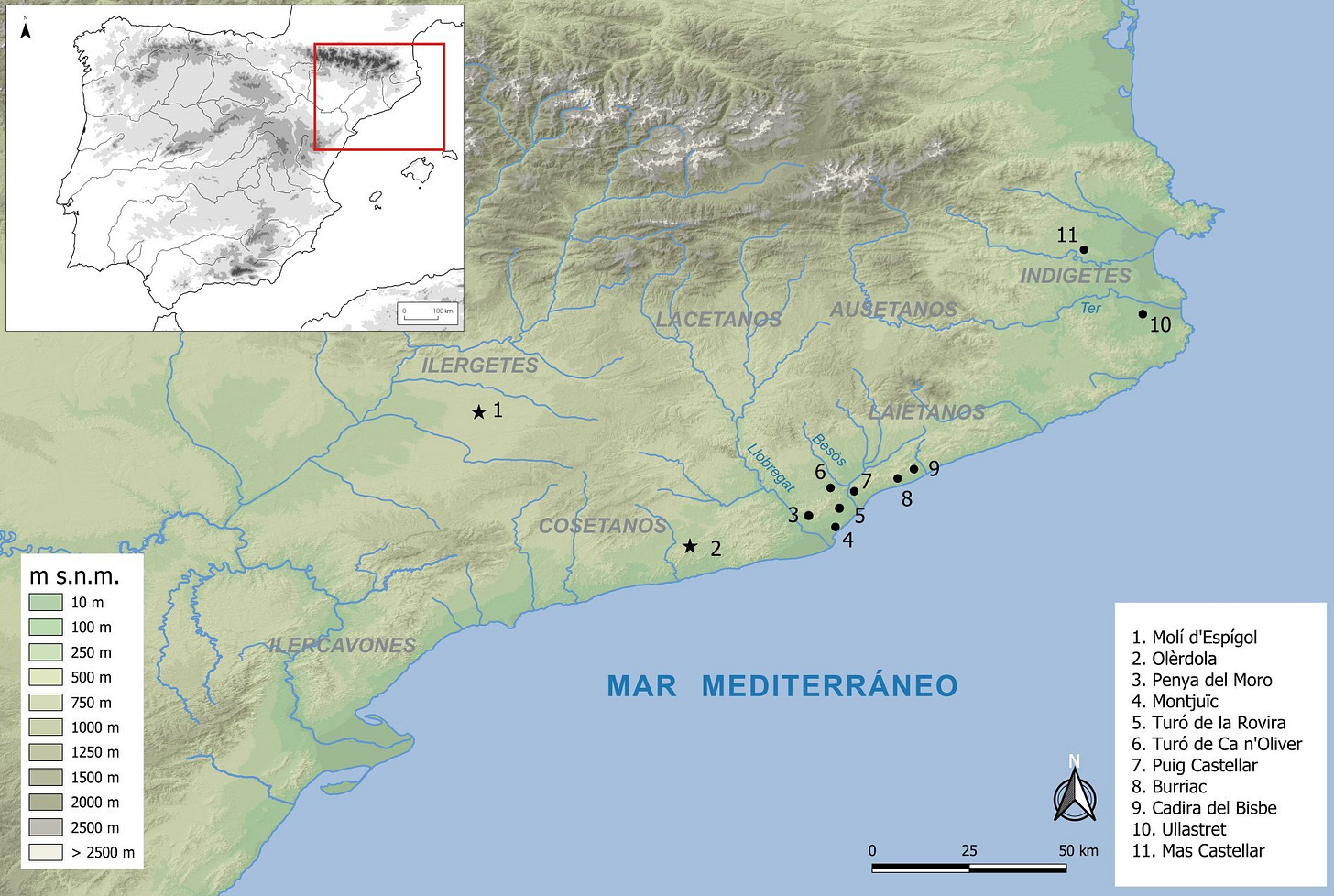

The Olèrdola fragments are the first evidence of the so-called “severed head” ritual among the Cosetani, one of the Iberian peoples who occupied the northeastern corner of the peninsula during the Iron Age. For decades, archaeologists assumed this practice belonged exclusively to groups living north of the Llobregat River: the Indigetes around Ullastret and the Laietani near the coast. The river marked a cultural boundary. South of it, different rules applied.

But boundaries, it turns out, are rarely as clean as we draw them.