The thing about museum collections is that most of what sits in storage got catalogued once, decades ago, by someone working through crate after crate of artifacts with a deadline and a typewriter. Brief notes. Minimal detail. The object goes into a drawer. File closes. Done.

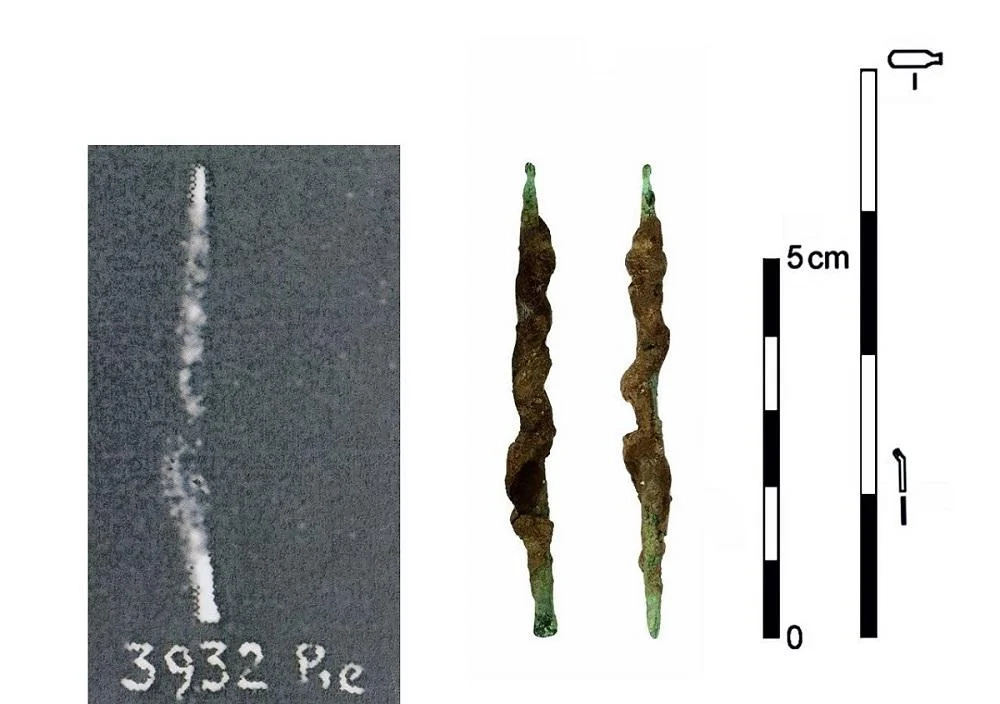

That’s what happened to item 1924.948 A at Cambridge’s Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. The catalog entry from the 1920s read: “a little awl of copper, with some leather thong wound round it.” Excavated from Grave 3932 at Badari in Upper Egypt. Adult male burial. Predynastic period, meaning sometime in the late fourth millennium BCE. Before the pharaohs. Before the pyramids. Before hieroglyphic writing had fully developed.

The object is 63 millimeters long. Weighs about 1.5 grams. Easy to overlook.

But when Martin Odler and Jiří Kmošek put the object under magnification recently,1 they saw something the original excavators missed. Fine parallel lines along the tip. Rounded edges. A slight bend near the working end. These aren’t damage marks. They’re use traces. Specifically, they’re the traces you get from spinning something very fast against hard material.

This wasn’t an awl at all. It was a drill. And those six coils of dried leather clinging to the shaft? They weren’t just wrapping. They were part of the mechanism.