When the Climate Got Better, the Plants Disappeared

Machine learning reveals that the ancestors of wheat and barley were less common after the Ice Age ended, not more.

Here’s what we know about the origins of agriculture in West Asia: it happened around 12,000 years ago. We know this from seeds and tools and animal bones pulled from archaeological sites across the region. We can trace the domestication process in grain morphology, watch shattering rachises give way to non-shattering ones, see wild stands become cultivated fields.

Here’s what we don’t know: where the first farmers actually found the plants they domesticated.

It sounds like a strange gap. But plant distributions shift. They contract and expand with climate, retreat to refugia during harsh periods, colonize new ground when conditions improve. The assumption, mostly unstated, has been that these shifts were modest. That if you want to know where wild wheat grew 12,000 years ago, you can look at where it grows today and assume rough continuity.

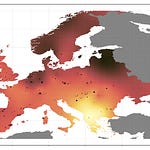

A new study in Open Quaternary1 shows that assumption is wrong. Using machine learning trained on modern plant occurrence data and paleoclimate simulations, Joe Roe and Amaia Arranz-Otaegui reconstructed the likely distributions of 65 plant species associated with early farming sites in West Asia. The list includes the wild ancestors of wheat, barley, rye, lentils, chickpeas, and flax.

The results are strange. Most of these species had smaller ranges in the Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene than they do today. Not slightly smaller. On average, about 25% smaller from the terminal Pleistocene to the Early Holocene. And that shrinkage happened as the climate warmed.