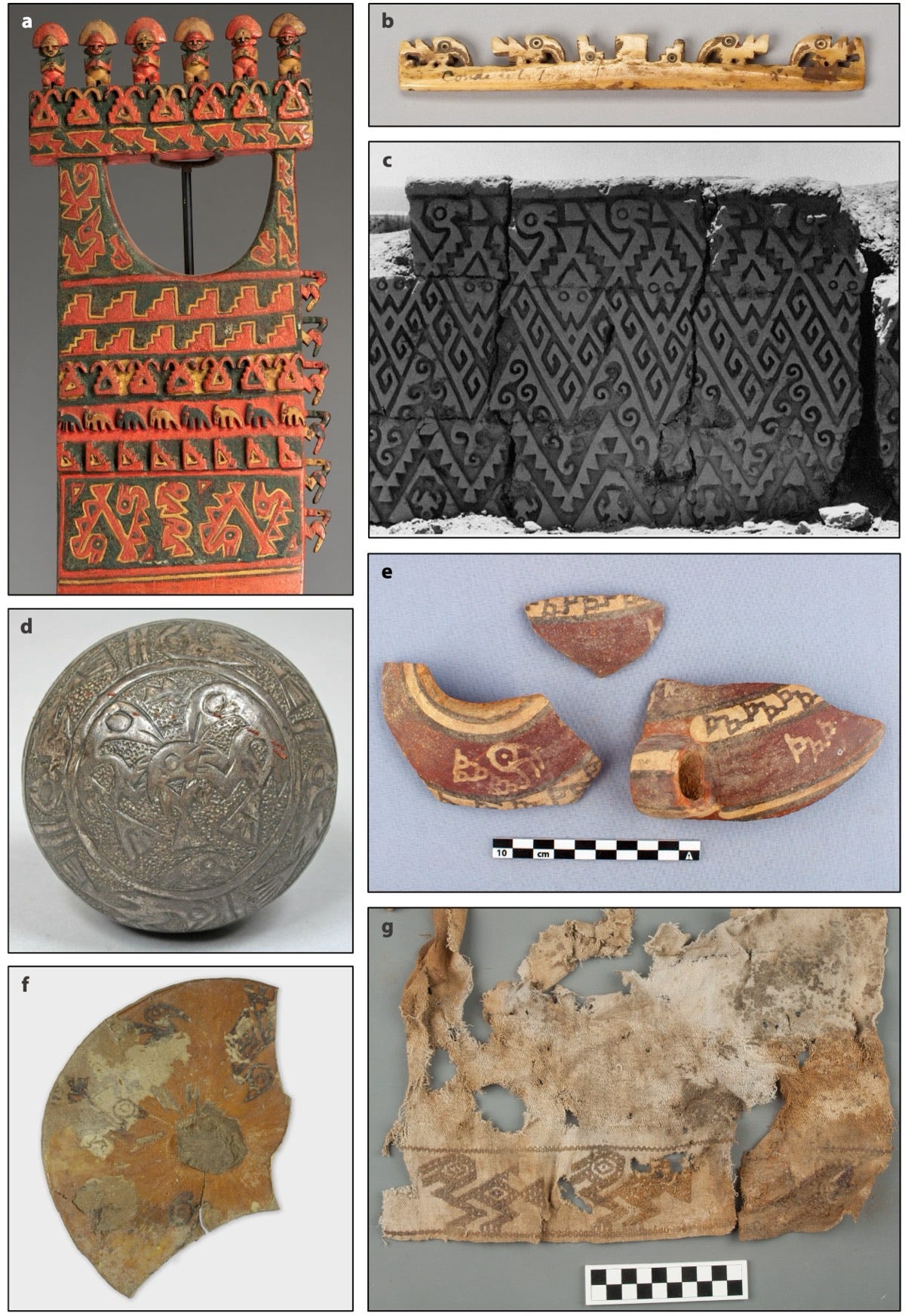

The Chincha Kingdom controlled a stretch of Peru’s southern coast between roughly 1000 and 1400 CE. By the time the Inca arrived, Chincha was wealthy enough and organized enough to negotiate terms rather than simply be conquered. The Spanish, arriving later, found a society that reportedly commanded 30,000 tribute payers, organized into specialized groups of farmers, fishers, and long-distance traders. When Francisco Pizarro made his way to Cajamarca in 1532, the Chincha lord rode alongside Atahualpa himself, one of the Inca’s final rulers. Only two litters. That proximity meant something.

But where did that wealth come from? The Chincha Kingdom sat in a coastal desert, one of the driest regions on Earth. Productive, yes, when you have a river valley and irrigation. But productive enough to support that kind of centralized political organization? Scholars have suggested various answers: maritime trade, access to highly valued mollusk shells, strategic location for coastal and highland exchange networks.

A team of archaeologists1 has now added another factor to the mix, and it’s both mundane and remarkable. They analyzed the nitrogen isotope ratios in ancient maize cobs excavated from tombs across the Chincha Valley. What they found points to widespread use of seabird guano as agricultural fertilizer, at least by 1250 CE and likely earlier. The practice wasn’t unique to Chincha. Similar evidence exists from northern Chile. But the Chincha Kingdom’s proximity to some of the world’s richest guano deposits, the nearby Chincha Islands, may have given farmers there a particular advantage. That advantage, the researchers argue, wasn’t just agricultural. It was political.