Three teeth from a burial ground in northern Vietnam are black. Not stained brown from decay or diet. Black. The kind of glossy, deep black that doesn’t happen by accident.

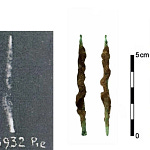

The teeth come from Dong Xa, a late Dong Son period site in Hung Yen Province. They’re approximately 2,000 years old, dated through radiocarbon analysis of organic materials from one of the burials. When researchers examined them under scanning electron microscopy and portable X-ray fluorescence, they found something unexpected:1 unusually high concentrations of iron and sulfur embedded in the enamel surface.

That chemical signature matters. It points to iron sulfate compounds, either from mineral sources or from reactions with iron-containing utensils, likely combined with tannin-rich plant materials. This isn’t incidental staining from diet. This is the residue of a deliberate, technically sophisticated practice.

Tooth blackening.

The practice sounds alien to anyone raised on Western standards of dental aesthetics. Whitening, bleaching, polishing to a gleam. But in Vietnam, blackening teeth was widespread by the early 20th century, practiced across majority and minority ethnic groups regardless of gender or social class. French colonial observers in the late 1800s called it “an absolute dark abyss in the mouth” and dismissed it as barbaric. They missed the point entirely.

Blackened teeth marked boundaries. Maturity versus childhood. Human versus animal. Civilization versus what lay outside it. In some oral traditions, black teeth distinguished people from devils. In others, they served as an identity marker for those abducted by foreign invaders. The practice encoded deep social meaning, and it required real technical skill.

The Vietnamese method was elaborate. First, sanitization. Teeth were cleaned and etched with acidic agents like lime juice or vinegar, roughening the enamel surface. This took about three days. Then came red dyeing. A paste made from tannin sources like stick-lac powder, mixed with acidifiers, was heated and applied to leaf strips that adhered to the teeth overnight. Eight to fifteen days of this. Next, black dyeing. A similar paste, but now incorporating iron sources—vitriol, or the mixture placed on metal utensils to pick up iron compounds—combined with tannins, adhesives like honey or glutinous rice, and flavorings such as cinnamon or star anise. Another two to eight days. Finally, polishing with burnt coconut shell powder or tar, often applied via metal tools.

The whole process could take more than twenty days. The result was stable, glossy black teeth that lasted a lifetime, requiring only minor touch-ups every few years.