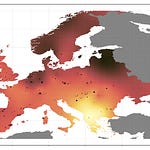

The standard story of Neolithic Europe runs like this: farmers arrive from Anatolia, sweep across the continent, and within a few centuries the genetic signature of hunting and gathering communities fades to nearly nothing. Ten percent here, maybe twenty there, absorbed into populations that are overwhelmingly descended from people who planted wheat and herded cattle.

The Low Countries didn’t follow that script.

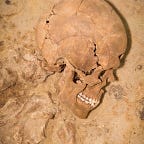

New ancient DNA analysis1 of 112 individuals from the Rhine-Meuse delta, spanning roughly seven thousand years, reveals something strange. Between about 5500 and 3000 BCE, while farming ancestry climbed to 70 or even 100 percent across much of Europe, communities in what is now the Netherlands, Belgium, and northwestern Germany kept their forager roots. Not as trace elements. As the dominant strand of their genetic makeup.

Some individuals living around 3000 BCE still carried about half their ancestry from local hunter-gatherers. The same hunter-gatherers whose descendants had been living in those river valleys and coastal wetlands for millennia.

The finding matters because it rewrites our understanding of how cultural and genetic change moved through prehistoric Europe. And because this region of prolonged continuity later became the launching point for one of the most dramatic population replacements in European prehistory.