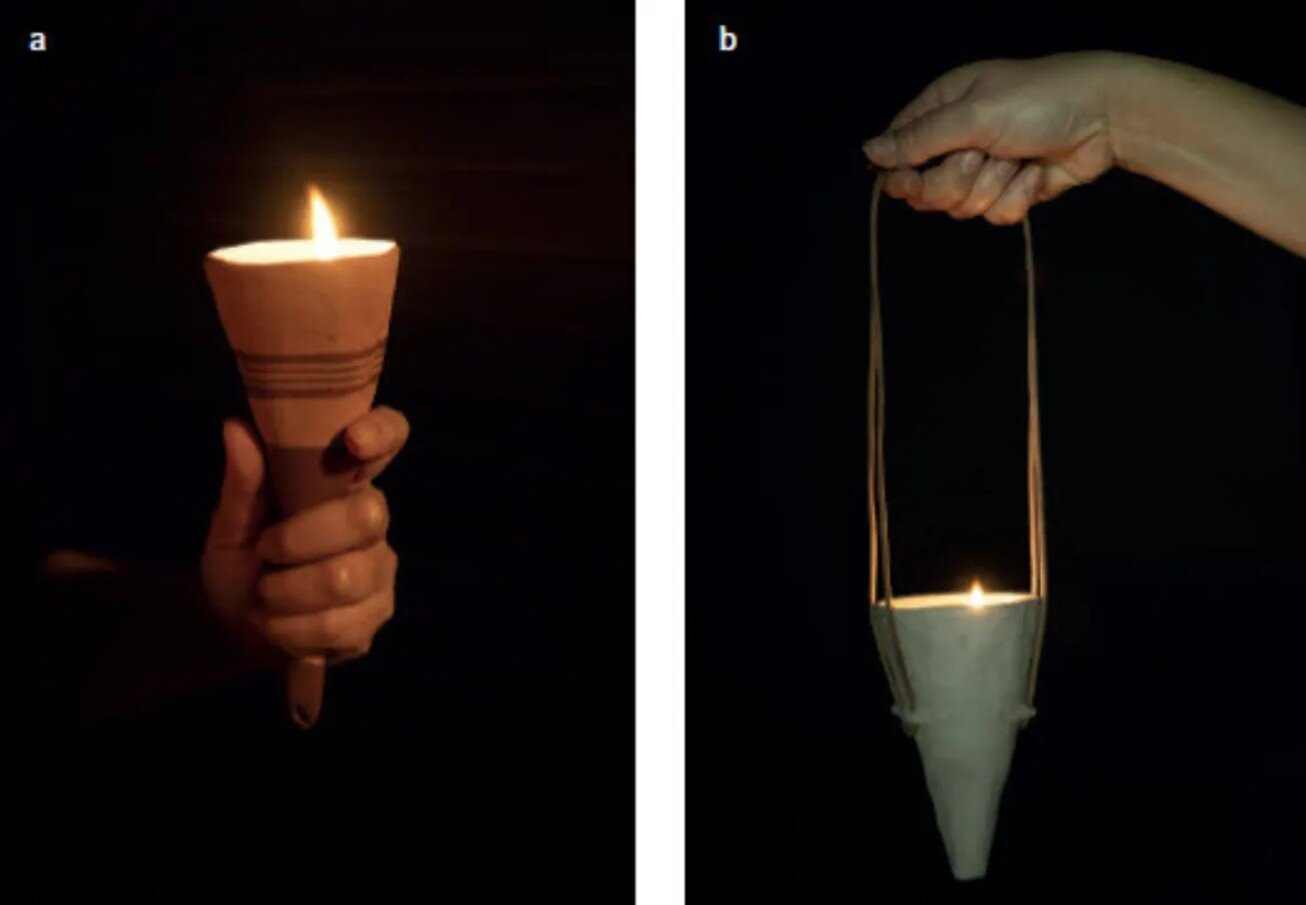

Imagine preparing for a ceremony by making your own lamp. Not ordering one, not receiving one from a specialist, but sitting down with clay and a stick and pulling together a crude cone in about ten minutes. The outside might be carefully smoothed and slipped red. The inside stays rough, unfinished, marked by your thumbs and the tool you used to hollow it out. You’ll fill it with beeswax later, when you join the procession.

This is one way to understand the cornets of Teleilat Ghassul.

These are small ceramic vessels, cone-shaped with pointed bases, produced only during the Chalcolithic period in the southern Levant, roughly 4500 to 3600 BCE. They turn up by the hundreds at certain sites. At others, they’re rare or absent entirely. The pointed base means they can’t stand on a flat surface. They have to be held, stuck into soft ground, or hung by small handles pierced horizontally near the rim. They’ve been called a fossile directeur of the period, but nobody has been entirely sure what they were directing anyone toward.

Sharon Zuhovitzky, Paula Waiman-Barak, and Yuval Gadot recently published the first systematic study1 of a large cornet assemblage from Teleilat Ghassul, a cluster of mounds in the Dead Sea basin. They examined 35 complete vessels and approximately 550 sherds stored at the Pontifical Biblical Institute in Jerusalem, material excavated intermittently between 1929 and 1999. What they found challenges the usual categories archaeologists use to sort ancient ceramics into either everyday household production or specialized craft production for ritual use.

The cornets fit neither model cleanly.