Archaeology has spent decades learning to see the people it used to overlook. Women. Children. Rural farmers. The urban poor. Each of these groups required someone to ask a new question, look at familiar evidence differently, and build a methodology from scratch. The results transformed how we understand ancient societies.

The elderly never got that treatment.

It’s a strange gap when you think about it. Old people were arguably the most socially significant demographic in ancient societies, not the most numerous, but the most powerful. They held property, adjudicated disputes, presided over households that spanned multiple generations. Biblical texts reference them constantly. Ethnographic parallels from traditional societies across the Middle East, Africa, and elsewhere show consistent patterns: age conferring authority, the oldest man in the family functioning as something close to a small-scale patriarch-ruler. In many non-industrial societies, as one anthropological overview put it, rank rises with age.

And yet archaeology mostly ignored them. The handful of studies that did engage with old age focused almost entirely on skeletal remains from cemeteries: how to identify biological age in bones, what physical conditions the elderly suffered, how they were treated in death. Useful work. But limited, for two reasons.

First, mortuary evidence for most of Iron Age Israel is sparse and badly fragmented. Burial caves from Judah in the eighth and seventh centuries BCE tend to have their bones transferred to communal repository pits for secondary burial, where individual skeletons become impossible to isolate. You cannot tell who was old.

Second, and more fundamentally, “old” is not just a biological state. It’s a social category. An enslaved person of sixty might be addressed as “boy” regardless of age. A particularly wise young man might be treated as an elder. The distinction matters. To understand old age in the past, you need to find it where old people actually lived: inside houses.

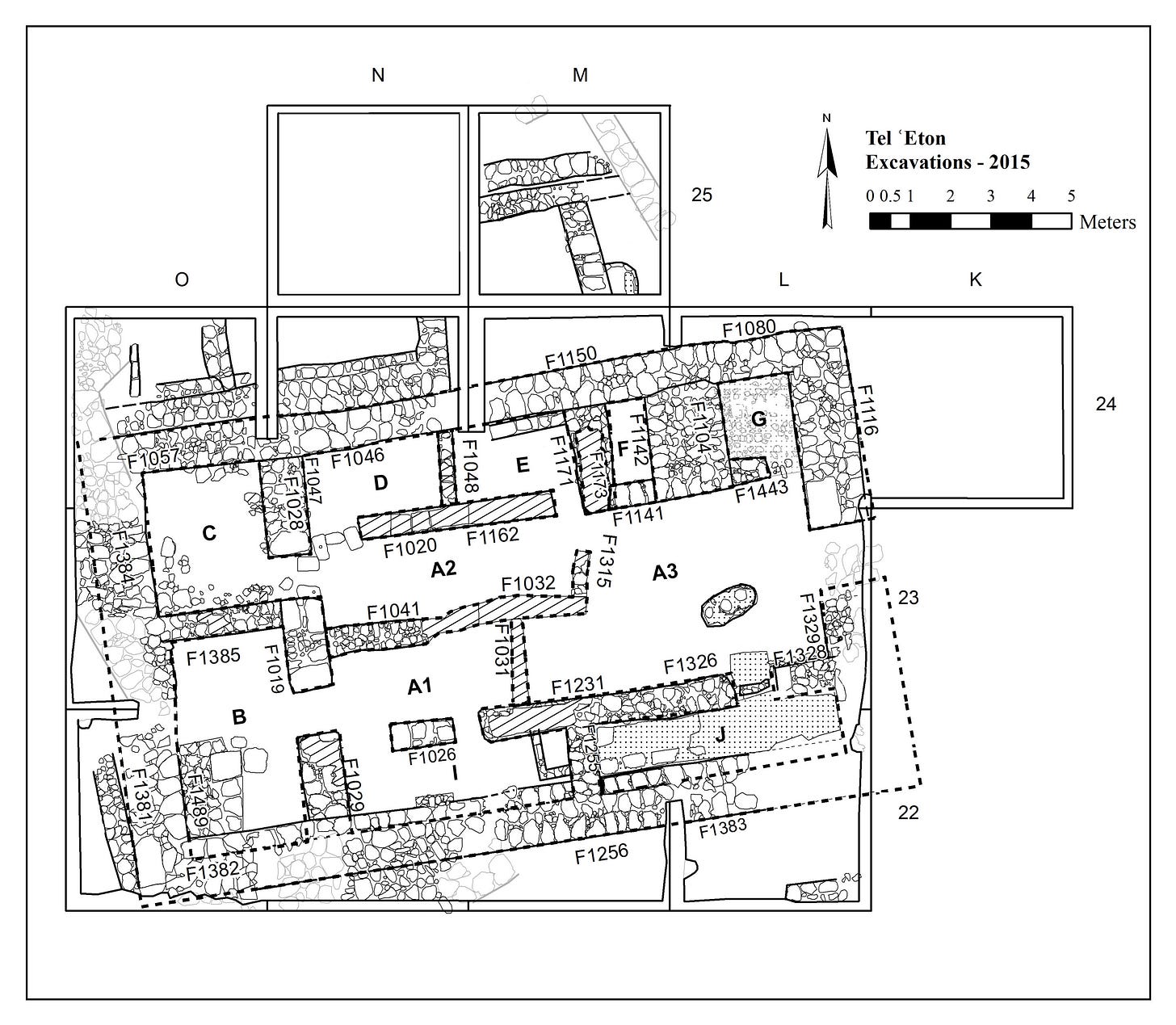

That’s what a recent paper by Avraham Faust, published in the Cambridge Archaeological Journal,1 attempts to do. The site is Tel ʿEton, in the southeastern Shephelah. The building is a large, two-storey four-room house. The moment is the late eighth century BCE, when the Assyrian army destroyed the settlement and, in doing so, accidentally preserved it.