Three skulls found in the clay banks of the Han River in central China have just gotten a lot older.

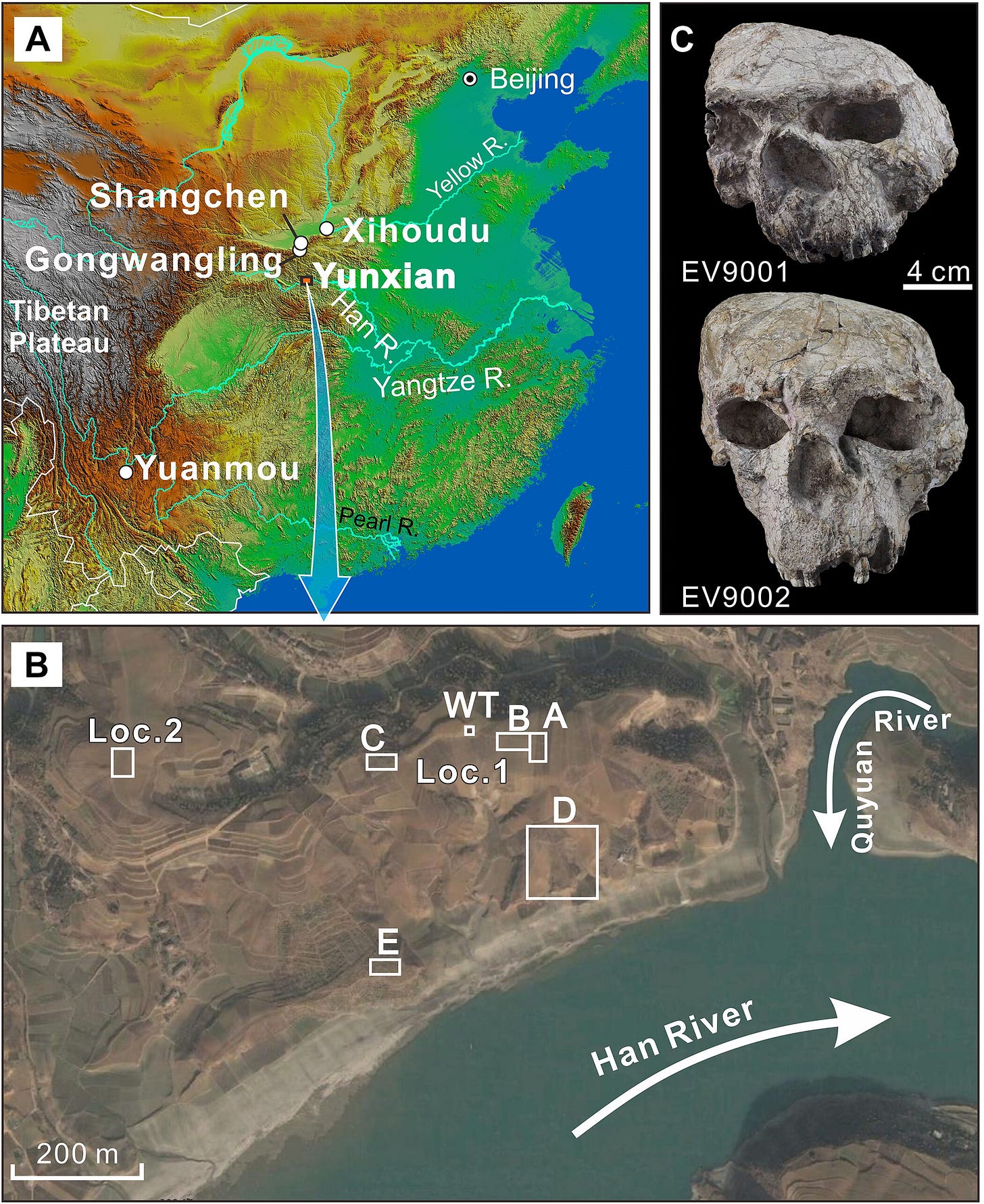

The fossils come from Yunxian, a site in Hubei Province that has been known since 1989, when local archaeologists turned up the first of two nearly complete Homo erectus crania during a survey. A third was found in 2021. Together they represent some of the most intact early hominin remains ever recovered in eastern Asia. The problem, for decades, was that nobody could agree on when these individuals actually lived. Early paleomagnetic work suggested the fossils predated the Brunhes-Matuyama geomagnetic reversal, implying an age somewhere around 870,000 to 830,000 years ago. Electron spin resonance dating of associated animal teeth gave a mean of around 600,000 years. Later work triangulated a range of roughly 800,000 to 1.1 million years.

None of that held up.

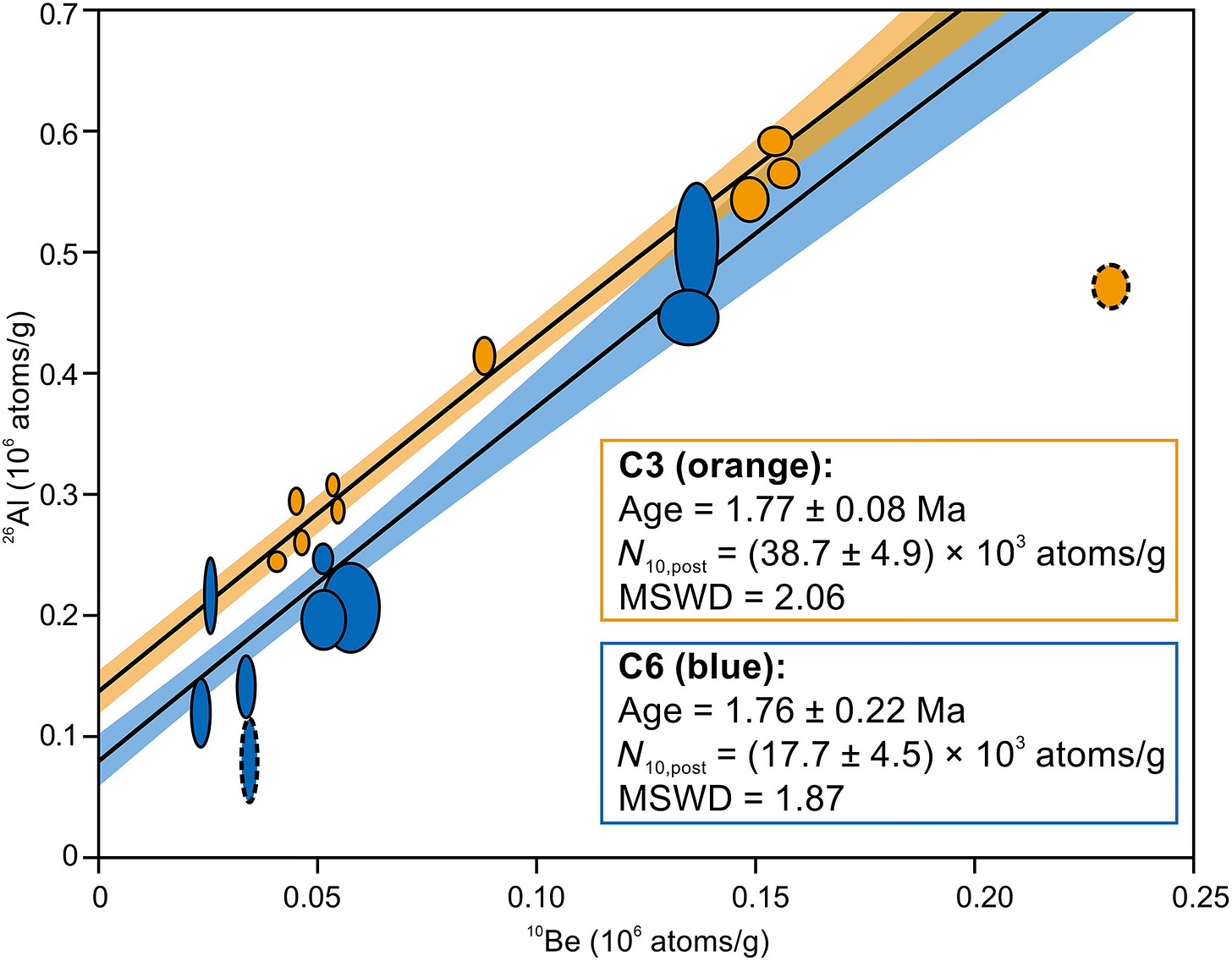

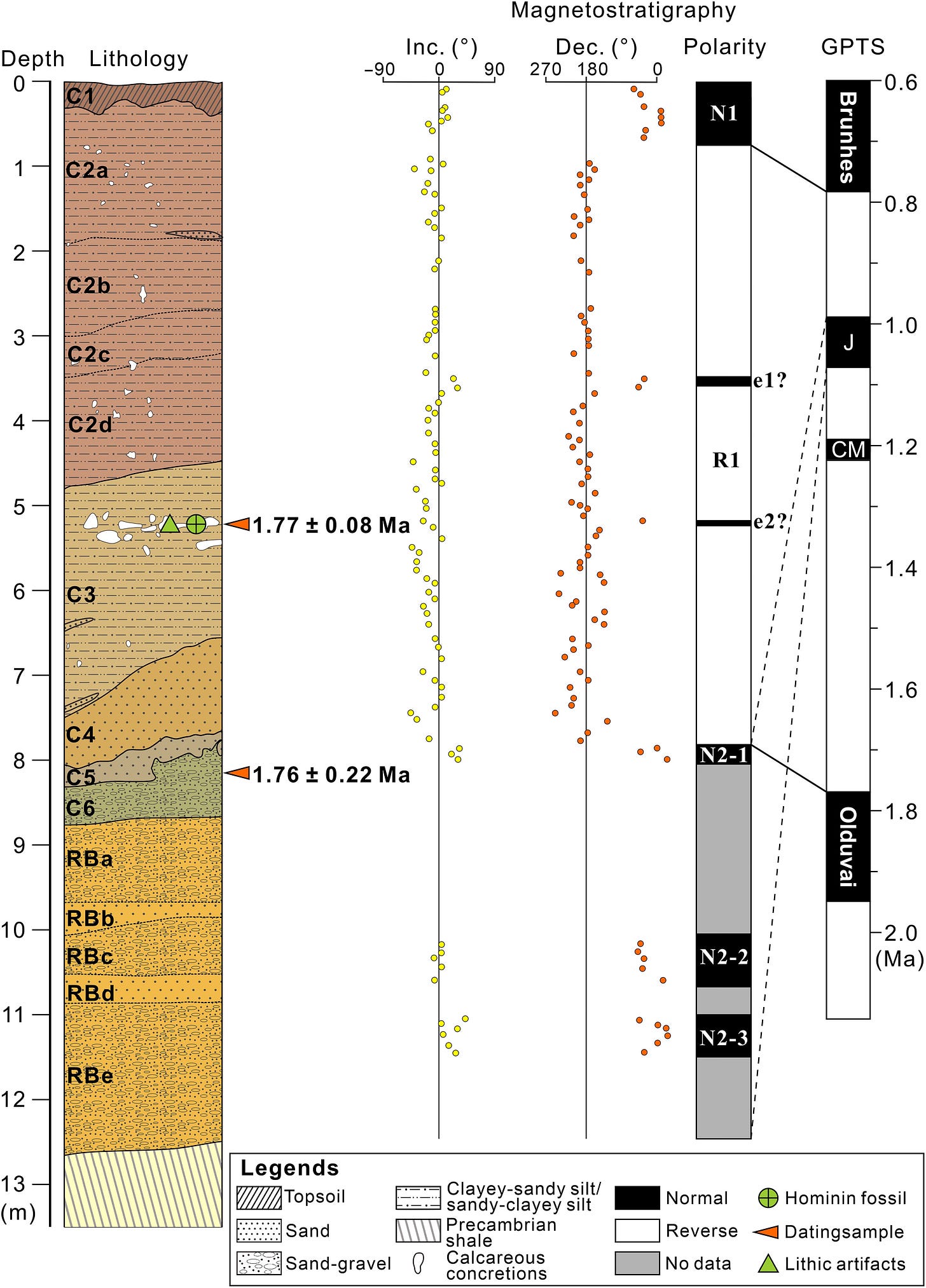

A team led by Hua Tu of Shantou University and Nanjing Normal University has now applied isochron ²⁶Al/¹⁰Be burial dating to quartz gravels pulled directly from the fossil-bearing sediment layer. Their result:1 1.77 ± 0.08 million years ago. With total uncertainty incorporated, the error extends to ±0.11 Ma. A second, deeper sediment layer dated independently to 1.76 ± 0.22 Ma, which is consistent within the error ranges. Two independent measurements from the same site, pointing at the same moment in the Early Pleistocene.

That is not a minor revision. It pushes the Yunxian Homo erectus back by at least 670,000 years from previous estimates. It makes these skulls the oldest securely dated H. erectus fossils found in their original context anywhere in eastern Asia.

How You Date Sediments That Old

The method behind this result is worth understanding, because it’s what separates this finding from the long line of contested Yunxian ages that came before.

Cosmogenic burial dating works because the same cosmic rays that constantly bombard Earth’s surface produce specific radioactive isotopes inside quartz minerals. Two in particular, aluminum-26 and beryllium-10, accumulate in quartz at known rates while rock and sediment sit near the surface. When that material gets buried deeply underground, the cosmic ray flux drops dramatically. Production stops. Radioactive decay continues. And because ²⁶Al and ¹⁰Be decay at different rates, their ratio shifts in a predictable way over time. Measure the ratio, compare it to known production and decay constants, and you can calculate how long the quartz has been underground.

The standard “simple burial” version of this technique has existed for decades, but it carries a significant limitation: it assumes the sediment was buried quickly and deeply enough to stop all postburial isotope production, and that the burial event happened only once. Those assumptions fail fairly often. The isochron approach, which the Yunxian team used, is more sophisticated. Instead of relying on a single sample, it uses multiple clasts from the same depth and plots their ²⁶Al and ¹⁰Be concentrations together. Samples with different pre-burial exposure histories will lie along a consistent line if they share the same burial age. Outliers, sediments reworked from older deposits or samples with complicated burial histories, fall off that line and can be identified and excluded. One sample from the fossil-bearing layer did exactly that and was removed from the calculation.

The team collected ten quartzose clasts from the same horizon where the crania were found, and another ten from a deeper gravel layer. Nine of the ten from the fossil layer yielded a clean isochron. The fact that some of the dated samples bore traces of hominin modification, knapping marks and possible manuport transport, ties the dating directly to a period of human occupation, not just sediment deposition.

There is also an independent geomorphological check. Previous studies had assigned a normal polarity zone in the lower sediments to the Jaramillo subchron (roughly 990,000 to 1,070,000 years ago). The new dates imply that zone actually corresponds to the Olduvai subchron, which ran from about 1.78 to 1.95 million years ago. That’s not a small reassignment, and it requires recalibrating the entire paleomagnetic interpretation of the site. The team argues this is actually the more parsimonious reading, consistent with the burial ages and with the broader geomorphological framework of the Han River terrace sequence.

One footnote worth flagging: the dating samples were collected from Trench WT, roughly 75 to 78 meters from two of the crania and 43 meters from the third. The researchers document the consistency of the sediment layer across all three trenches based on color, grain size, sedimentary structure, and the presence of a distinctive calcareous concretion horizon. That consistency is reasonable but still an inference, not a direct measurement from the skull-bearing sediment itself.

Where This Leaves the Broader Picture

The figure that keeps coming up when people think about Homo erectus in Asia is Dmanisi, in the Republic of Georgia. The hominins there date to between 1.78 and 1.85 million years ago, recovered from sediments at the top of the Olduvai subchron. For years, Dmanisi sat at or near the leading edge of the H. erectus dispersal out of Africa, the earliest confirmed stop on a route that presumably continued east across the continent.

At 1.77 Ma, Yunxian is marginally younger than Dmanisi, likely by a small margin within the error ranges. That alone is not shocking; H. erectus had to get from Georgia to central China somehow. But the speed implied is striking. If the species was already in the Caucasus by 1.8 million years ago and present in the Han River basin of China by 1.77 million years ago, the dispersal across several thousand kilometers of Eurasia happened very fast, geologically speaking. The Yunxian dates strengthen what the team describes as a rapid dispersal model, the idea that early H. erectus spread quickly and widely across Asia shortly after 2 million years ago rather than advancing slowly in stages over many hundreds of thousands of years.

What makes that model stranger is the archaeology. The earliest stone tool sites in China predate both Dmanisi and Yunxian by a substantial margin. Xihoudu, in Shanxi Province, has been dated to around 2.4 million years ago using ²⁶Al/¹⁰Be burial dating. Shangchen, on the Chinese Loess Plateau, has evidence of hominin occupation extending back to roughly 2.1 million years ago. These sites predate the Yunxian hominins by 300,000 to 600,000 years. Something was making tools in China before H. erectus showed up, or at least before we have fossil evidence of H. erectus being there. The question of who that something was remains genuinely open.

Homo erectus in the traditional sense appears in the African fossil record at around 1.9 million years ago. If the Chinese archaeological sites at Xihoudu and Shangchen are real and reliably dated, and most researchers think they are, then whoever left those tools was either a very early and as-yet-unrecognized population of H. erectus, or an entirely different hominin. Neither option is comfortable. The first requires pushing the species’ origin earlier than current evidence supports. The second requires positing another hominin dispersal event for which we have no fossil record.

The Yunxian dates narrow the gap between the earliest Chinese archaeology and the earliest confirmed Chinese hominin fossils, but they don’t close it. They also raise the phylogenetic stakes. A 2025 study in Science used an assumed age of 1.0 million years for the Yunxian 2 cranium to anchor a phylogenetic analysis that placed those fossils at the base of a lineage including Homo longi and the Denisovans. At 1.77 million years, that whole analysis would need to be rerun. The team notes this directly, with some understatement.

These are three skulls from a river terrace in Hubei Province that nobody outside paleoanthropology has heard of. But the number attached to them just changed, and the implications are still expanding outward.

Further Reading

Feng, X., Yin, Q., Gao, F., Lu, D., Fang, Q., Feng, Y., Huang, X., Tan, C., Zhou, H., Li, Q., Zhang, C., Stringer, C., and Ni, X. (2025). The phylogenetic position of the Yunxian cranium elucidates the origin of Homo longi and the Denisovans. Science, 389, 1320–1324.

Zhu, Z., Dennell, R., Huang, W., Wu, Y., Qiu, S., Yang, S., Rao, Z., Hou, Y., Xie, J., Han, J., and Ouyang, T. (2018). Hominin occupation of the Chinese Loess Plateau since about 2.1 million years ago. Nature, 559, 608–612.

Shen, G. J., Wang, Y. R., Tu, H., Tong, H. W., Wu, Z. K., Kuman, K., Fink, D., and Granger, D. E. (2020). Isochron ²⁶Al/¹⁰Be burial dating of Xihoudu: Evidence for the earliest human settlement in northern China. Anthropologie, 124, 102790.

Luo, L., Granger, D. E., Tu, H., Lai, Z. P., Shen, G. J., Bae, C. J., Ji, X. P., and Liu, J. H. (2020). The first radiometric age by isochron ²⁶Al/¹⁰Be burial dating for the Early Pleistocene Yuanmou hominin site, southern China. Quaternary Geochronology, 55, 101022.

Tu, H., Shen, G. J., Granger, D. E., Yang, X. Y., and Lai, Z. P. (2017). Isochron ²⁶Al/¹⁰Be burial dating of the Lantian hominin site at Gongwangling in Northwestern China. Quaternary Geochronology, 41, 174–179.

Gabunia, L., Vekua, A., Lordkipanidze, D., Swisher, C. C. III, Ferring, R., Justus, A., Nioradze, M., Tvalchrelidze, M., Antón, S. C., Bosinski, G., Jöris, O., Lumley, M. A., Majsuradze, G., and Mouskhelishvili, A. (2000). Earliest Pleistocene hominid cranial remains from Dmanisi, Republic of Georgia: Taxonomy, geological setting, and age. Science, 288, 1019–1025.

Antón, S. C., Potts, R., and Aiello, L. C. (2014). Evolution of early Homo: An integrated biological perspective. Science, 345, 1236828.

Tu, H., Feng, X., Luo, L., Lai, Z., Granger, D., Bae, C. J., and Shen, G. (2026). The oldest in situ Homo erectus crania in eastern Asia: The Yunxian site dates to ~1.77 Ma. Science Advances, 12(8), eady2270. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.ady2270