There’s something quietly strange about wheat. It covers more of the earth’s surface than almost any other crop, feeds billions of people, and has been shaped by human hands for roughly ten thousand years. And yet, for a large portion of that time, the humans shaping it had no idea what they were doing. They were selecting for traits they could see and use. They had no framework for understanding what they were simultaneously selecting against.

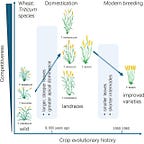

A study published in Current Biology1 earlier this year brings that hidden history into focus. The research, led by Yixiang Shan and Colin Osborne at the University of Sheffield in collaboration with teams in Madrid and Wageningen, examined how wheat changed during its earliest period of domestication — not just in grain size or husk structure, which is where most domestication research lands — but in something more behavioral. They were looking at how competitive the plants became. How aggressively they fought each other for light and space.

The answer, it turns out, is very.

Over somewhere between 1,000 and 2,000 years of early cultivation, wheat evolved what the researchers describe as “warrior” phenotypes. Larger leaves, held at steeper angles. A stronger ability to keep growing even when surrounded by rivals. The plants that survived in early managed fields weren’t just productive — they were combative. They had been shaped, unintentionally, by the act of farming itself.

The mechanism is straightforward once you see it. When early farmers began planting seeds in managed plots, they created a new selective environment. Wild Triticum populations were spread across varied terrain, competing against a diverse community of other species. But in a managed field, the competition shifts. Suddenly you’re surrounded by your own kind, packed at high density, all reaching for the same light from the same soil. The plants that thrived under those conditions were the ones that could outgrow their neighbors, literally overtop them, shade them out before they could establish.

Steeper leaf angles turned out to be the key trait. The team used functional-structural plant modeling to simulate growth under different competitive conditions, and the analysis pointed clearly to leaf angle as the most influential factor in determining which plants won. An upright leaf catches light from above while simultaneously casting shade downward. In a crowded field, that geometry is decisive.

This isn’t random drift. It’s selection operating fast and hard in a new environment — one that humans created without understanding they were creating an evolutionary arena.