There’s a site in the Jordan Valley that has been quietly unsettling our models of early human dispersal for decades. ‘Ubeidiya, a geological formation exposed along the western edge of the Dead Sea rift, contains Acheulean stone tools, the large bifacial hand axes associated with early Homo, alongside bones from animals now extinct and a faunal mix that doesn’t belong to any single biogeographic world. African species and Asian species, side by side, embedded in lake sediments that crept up from some ancient shoreline. The place is strange in the best possible way.

The problem has always been pinning down exactly when it formed. For a long time, the working estimate was somewhere between 1.2 and 1.6 million years ago, which would make ‘Ubeidiya a relatively late chapter in the story of hominins leaving Africa. Significant, yes, but not necessarily surprising. A new study changes that. According to a team led by Ari Matmon of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Omry Barzilai from the University of Haifa, and Miriam Belmaker from the University of Tulsa, the site is at least 1.9 million years old. That’s not a minor revision. That’s a different story entirely.

The study was published in Quaternary Science Reviews1 in 2026.

The previous age range wasn’t arbitrary. It came from relative chronology, the kind of dating that says this layer is older than that one and works by matching fossils or tool types to other sites with known ages. Relative chronology is useful, but it’s indirect. It answers questions by triangulation rather than measurement. What Matmon and colleagues did was go back to ‘Ubeidiya and take direct measurements, using three separate techniques that each probe the past in a different way.

The first is cosmogenic isotope burial dating. Cosmic rays constantly bombard Earth’s surface, and when they strike quartz or other minerals in exposed rock, they produce rare isotopes, including beryllium-10 and aluminum-26, at predictable rates. Once sediment is buried and shielded from further cosmic bombardment, those isotopes start to decay. The ratio of isotopes still present, compared to what would have accumulated at the surface, tells you how long the material has been underground. It’s essentially a clock that starts the moment a rock goes into the ground.

The second method reads Earth’s magnetic memory. When sediment settles in a lake, fine magnetic particles within it align themselves with the planet’s magnetic field, like tiny compasses frozen in place as the mud hardens. Earth’s magnetic field has flipped many times over geological history, and the pattern of those reversals is now well-established. By measuring the magnetic orientation locked into the ‘Ubeidiya lake sediments layer by layer, the team was able to match the site to a specific interval in the magnetic reversal record: the Matuyama Chron, a period that began more than two million years ago.

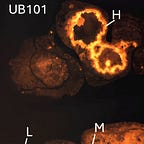

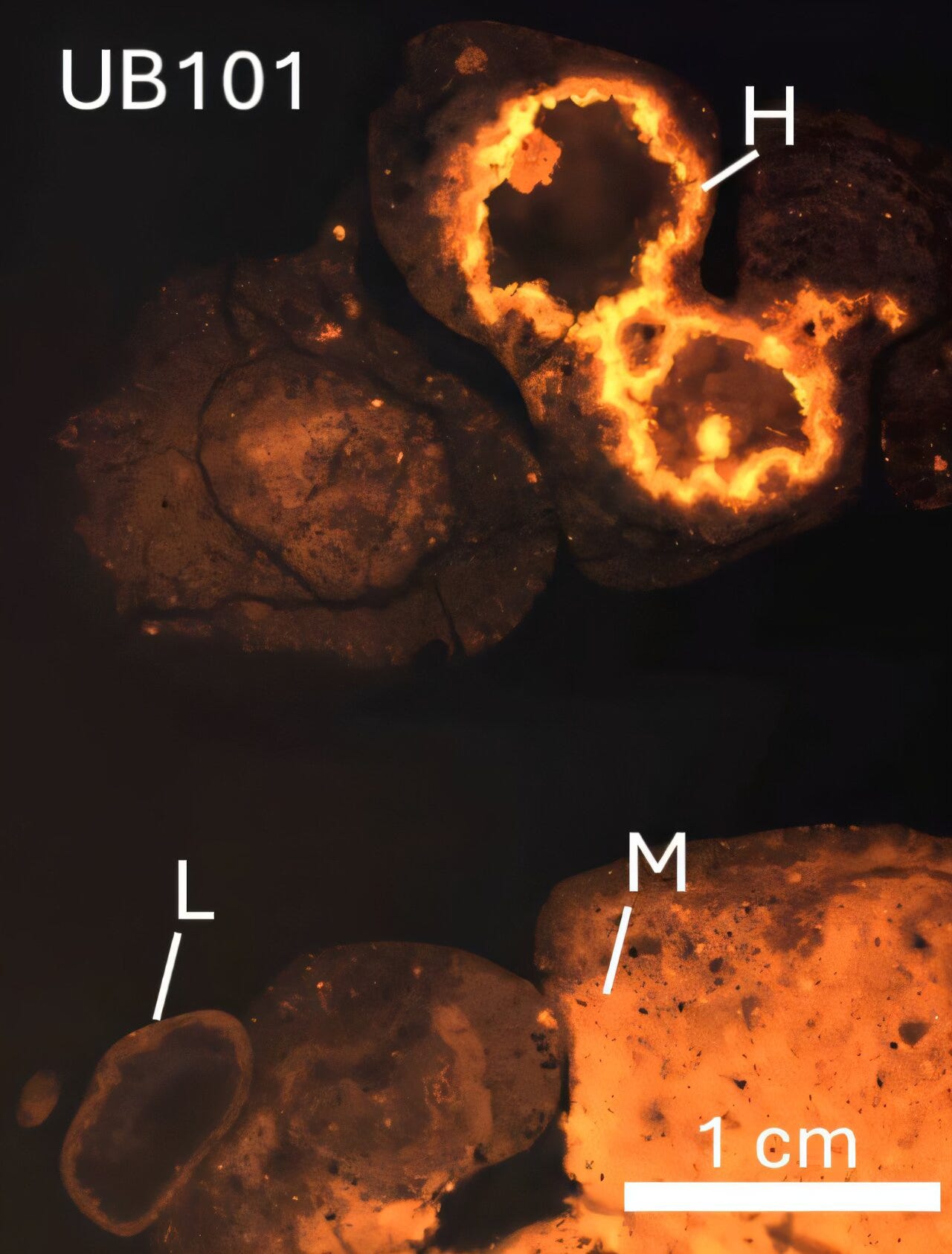

The third technique used uranium-lead dating on fossilized shells of Melanopsis, a freshwater snail found embedded in the sediment. Uranium decays into lead at a known rate, so the ratio of parent to daughter isotope in the shells gives a minimum age for the layer in which they were found.

Three methods. Three independent lines of evidence. All of them pointing to something considerably older than the previous consensus.