The birds that should not have been there

Scarlet macaws do not belong in the high desert of northwestern New Mexico. Their natural range lies far to the south, in tropical and subtropical landscapes where humidity, fruiting trees, and warmth are reliable. Yet for more than a century, archaeologists working in Chaco Canyon have been pulling macaw bones from masonry rooms built of sandstone and timber, hundreds of kilometers from the nearest viable habitat.

The puzzle has never been whether the birds were exotic. That much was obvious. The deeper question has always been how they lived, where they were kept, and what their presence meant to the people who built Chaco’s monumental great houses between the ninth and twelfth centuries CE.

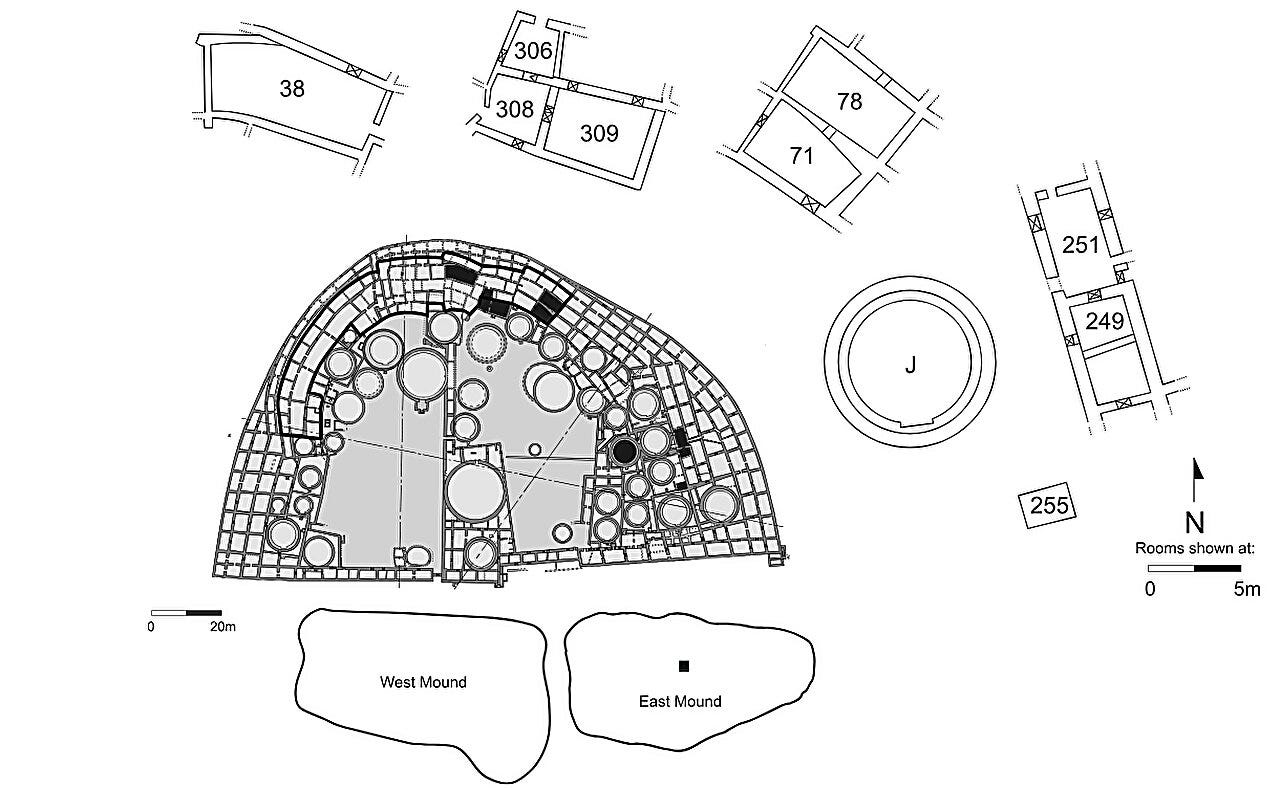

A new reanalysis1 by Katelyn Bishop offers a clearer, more grounded answer. By reconstructing the precise contexts in which macaws and parrots were found, the study shifts attention away from speculation about long-distance trade alone and toward the lived relationships between humans and birds inside Chacoan architecture.