A 4,000-year-old animal genome hints that early epidemics traveled along herding routes, not just human footsteps, and forces a rethink of how ancient societies lived with contagion.The most infamous plague in history has a familiar cast of characters. Yersinia pestis rides on fleas. Fleas ride on rats. Humans pay the price. This script fits the medieval Black Death so well that it has become a template for imagining all past pandemics.

But the Bronze Age version of plague refuses to follow that plot.

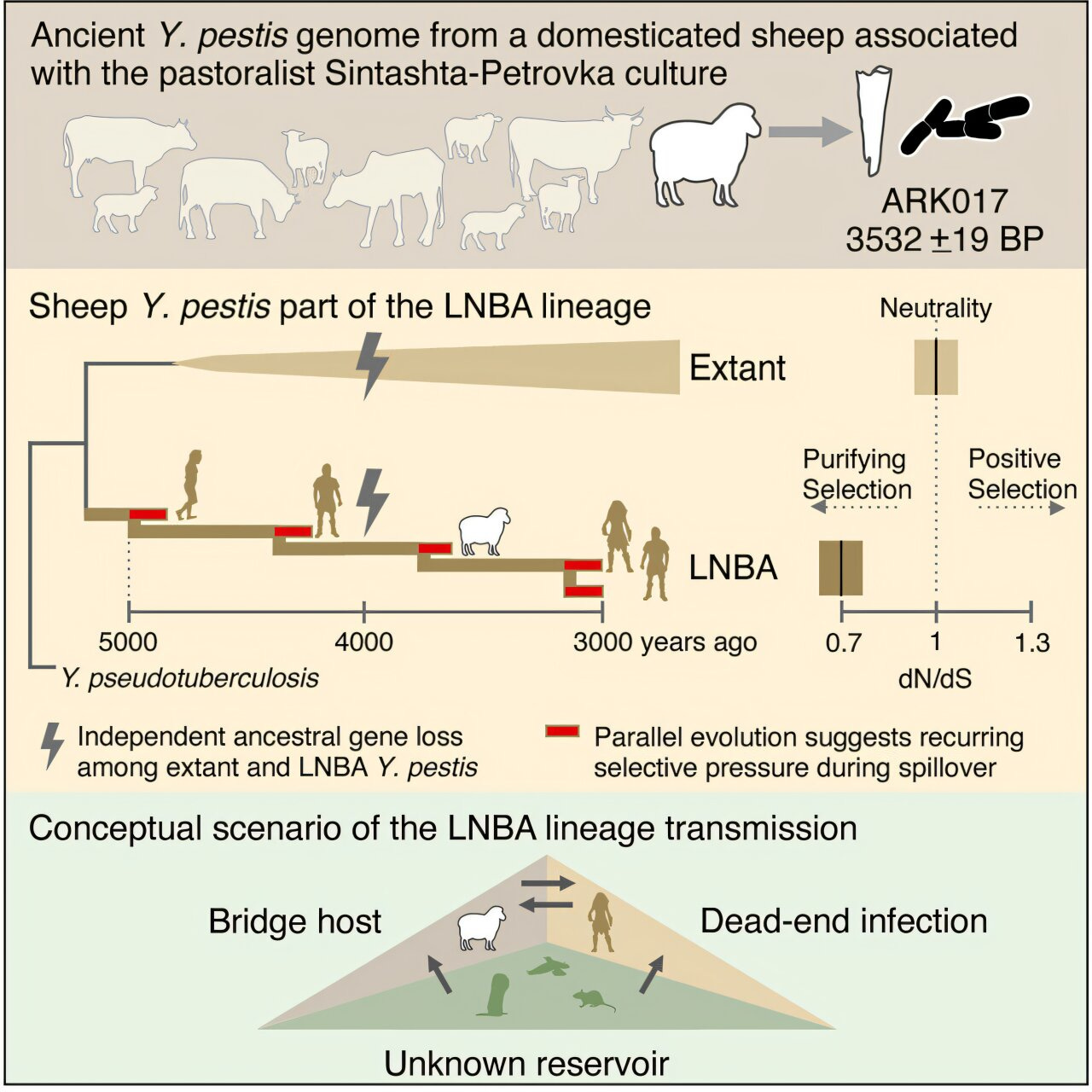

For years, ancient DNA studies have shown that an early lineage of Yersinia pestis spread across Eurasia between roughly 3000 and 1000 BCE. The genomes turned up in human remains separated by thousands of kilometers. Yet this strain lacked the genetic machinery needed for flea-borne transmission. No fleas, no rats, no obvious way to move so far, for so long.

A single sheep bone from the Eurasian steppe now offers a solution.1 It also complicates the story in ways that resonate far beyond epidemiology.