Along the Pacific coast of what is now northern Chile, the Atacama Desert meets the sea with little warning. It is one of the driest places on Earth, a landscape where bodies do not readily decay and where survival has always required careful attention to water, food, and kin. Thousands of years ago, people living here began to do something that still unsettles and fascinates archaeologists. They took their dead apart, piece by piece, and rebuilt them.

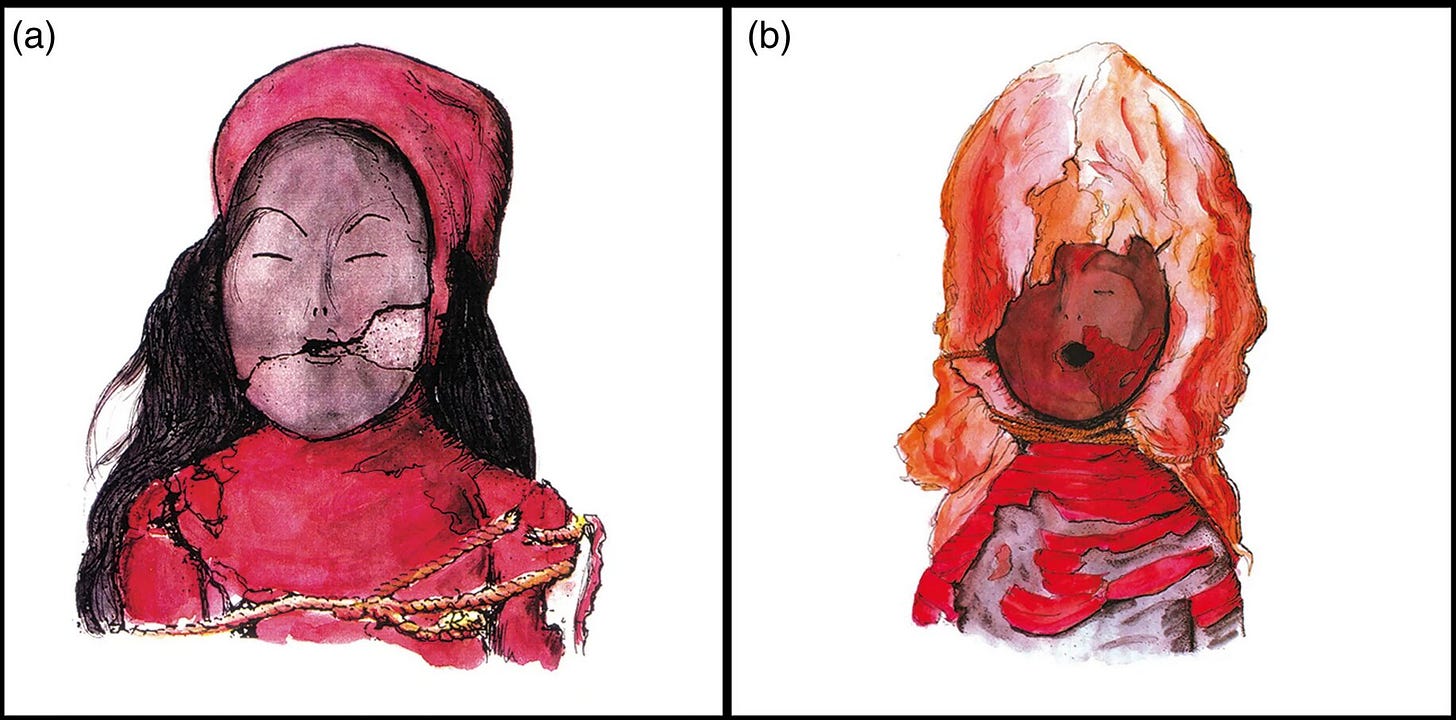

The Chinchorro people practiced artificial mummification nearly two millennia before the first Egyptian dynasties. Their methods were laborious, intimate, and visually striking. New work1 by bioarchaeologist Bernardo Arriaza invites a different way of understanding why this tradition began. Rather than seeing the earliest mummies as symbols of status or belief imposed from above, Arriaza frames them as a response to grief, especially the grief of losing children in a fragile world.