In a shallow gully on Kenya’s Homa Peninsula, scattered among ancient sediments, lie clues to a behavior that would eventually become distinctly human: carrying the right tools to the right place, even if that meant hauling them across many miles.

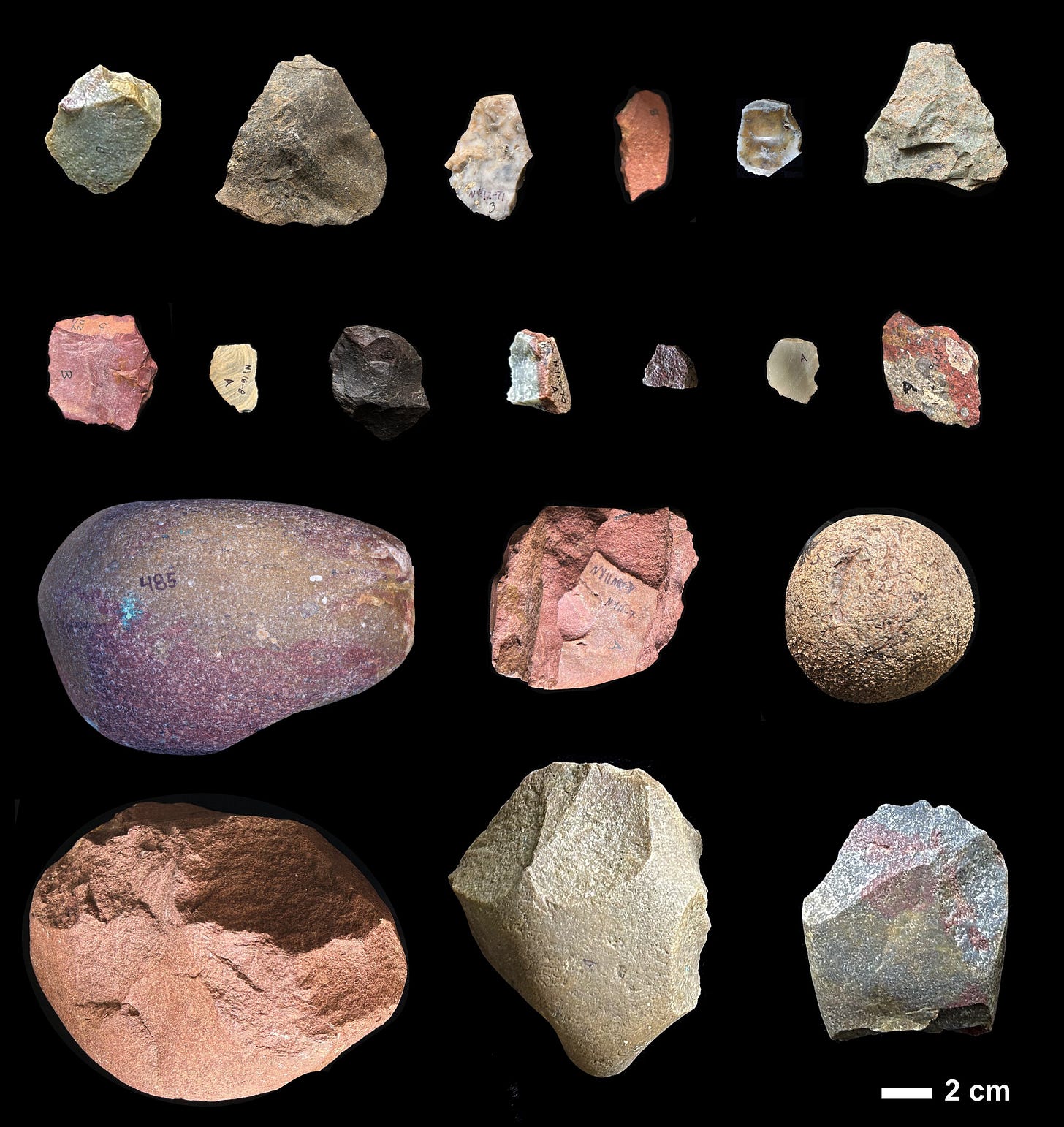

A recent study in Science Advances1 reports that early Oldowan toolmakers at Nyayanga, active at least 2.6 million years ago, selectively transported large, durable cobbles from sources up to 13 kilometers away. These stones—quartzite, rhyolite, and other tough rock types—were brought to a site where hominins processed plants, butchered hippopotamuses, and performed heavy pounding tasks. The research pushes back the earliest known evidence of such long-distance raw material transport by more than half a million years.

“The knowledge and intent to bring stone material to rich food sources was apparently an integral part of toolmaking behavior at the outset of the Oldowan,” said Rick Potts, co-author and head of the Smithsonian’s Human Origins Program.

A Landscape Without the Right Stones

The Homa Peninsula’s local geology posed a problem for toolmakers. Nearby rocks, altered by ancient volcanic processes, were softer and prone to shattering. For pounding through bone or slicing meat, they dulled too quickly. Instead, the Nyayanga hominins sought tougher material from river systems in the eastern highlands—stone that never naturally reached the peninsula.

Geochemical analysis revealed that more than 70 percent of the Nyayanga tools were made from nonlocal stone, much of it traceable to the Oboro region of the Awach Tende river basin, about 13 kilometers away. These cobbles were large, often exceeding 10 centimeters, and ideal for producing sharp-edged flakes or enduring repeated pounding.

“Nyayanga hominins were selective,” said lead author Emma Finestone of the Cleveland Museum of Natural History. “They bypassed smaller, poorer-quality stones in favor of bigger, better raw materials from far afield.”

Not Just Tools—Mental Maps

The distance alone is telling. While chimpanzees and other primates occasionally move stones, their transport distances rarely exceed a few kilometers. The Nyayanga toolmakers went far beyond that. The pattern of raw material use does not match the gradual “distance decay” seen when animals pick up and discard tools opportunistically. Instead, it suggests purposeful transport with minimal use en route—stones were carried intact to the site, where they were worked and discarded.

The behavior implies something important: a mental map of the landscape that linked distant raw material sources with predictable food-processing locations.

Whose Hands Held the Tools?

At Nyayanga, the tools were found alongside fossilized teeth from Paranthropus—a robust-jawed hominin traditionally not viewed as a habitual toolmaker. Whether these teeth belonged to the toolmakers remains uncertain, but their presence complicates the once neat division between Homo as the toolmaker and other hominins as tool users.

“Unless you find a hominin fossil actually holding a tool, you can’t be certain,” said Finestone. “But Nyayanga suggests a greater diversity of hominins making early stone tools than previously thought.”

Why It Matters

By at least 2.6 million years ago, hominins were integrating tool transport into their foraging strategies. This was not a matter of picking up whatever was at hand—it was deliberate provisioning, anticipating future needs, and linking separate parts of a landscape into a single behavioral system. The same strategy appears again 600,000 years later at another Homa Peninsula site, Kanjera South, suggesting it was a persistent feature of local hominin life.

In the words of Potts, “The mental maps of the oldest known hominins to persistently make stone tools well surpassed their immediate surroundings, even surpassing a few miles.”

Related Research

Braun, D. R., et al. (2008). “Oldowan behavior and raw material transport: Perspectives from the Kanjera Formation.” Journal of Human Evolution, 55(3), 409–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2008.05.004

Harmand, S., et al. (2015). “3.3-million-year-old stone tools from Lomekwi 3, West Turkana, Kenya.” Nature, 521, 310–315. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14464

Panger, M., et al. (2002). “Older than the Oldowan? Rethinking the emergence of hominin tool use.” Evolutionary Anthropology, 11(6), 235–245. https://doi.org/10.1002/evan.10094

Emma M. Finestone et al., Selective use of distant stone resources by the earliest Oldowan toolmakers.Sci. Adv.11,eadu5838(2025).DOI:10.1126/sciadv.adu5838