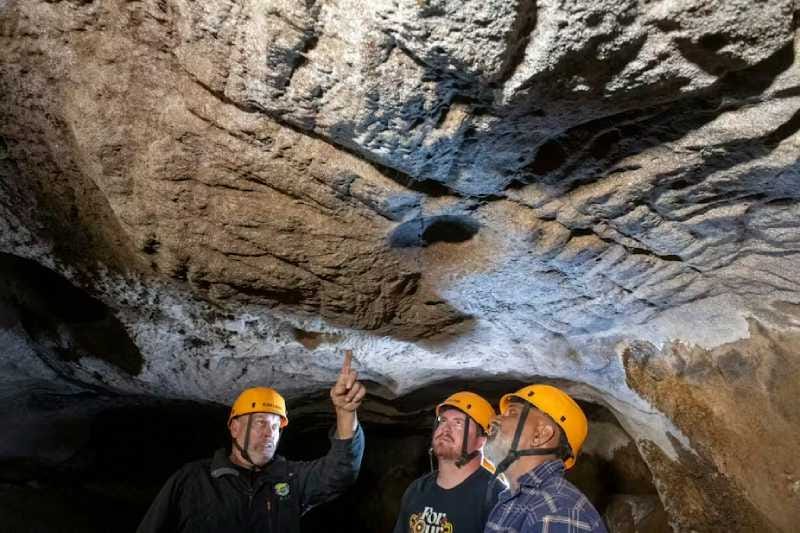

Deep in the foothills of the Victorian Alps lies Waribruk, a limestone cave whose walls glitter under lamplight. Today it is silent and still, but thousands of years ago, this was a place of movement, touch, and sacred purpose.

Archaeologists, working in partnership with the GunaiKurnai Land and Waters Aboriginal Corporation, recorded1 nearly a thousand sets of grooves pressed into the soft, crystal-coated walls and ceilings. These were not casual marks. They are the physical traces of hands—adult and child—dragged deliberately through stone softened by water and time.

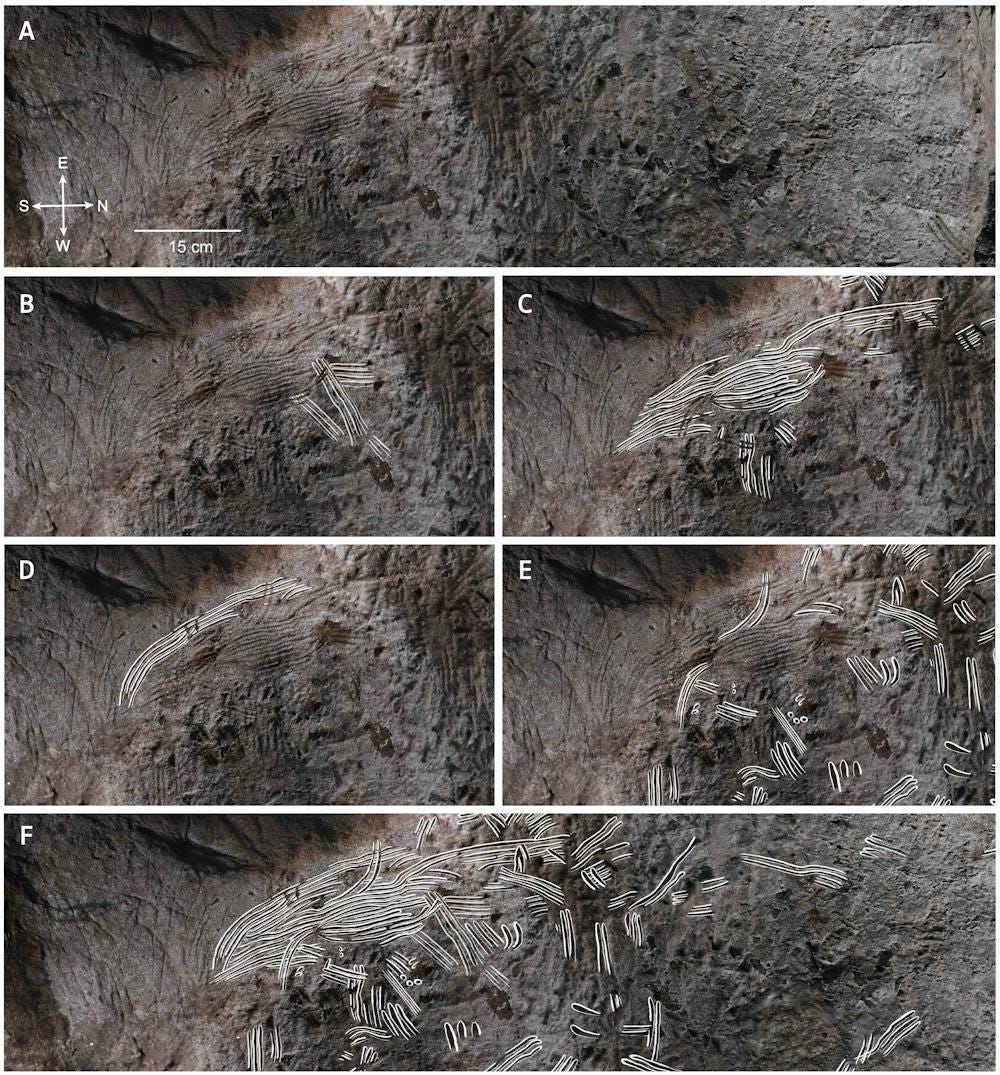

“The grooves occur only where calcite microcrystals coat the walls,” researchers note. “They never appear in areas of the cave without this glittering surface.”

Radiocarbon dating of tiny charcoal flecks and ash fragments, likely from firesticks, places the activity between 8,400 and 1,800 years ago. No hearths or domestic debris mark this space. Instead, oral traditions speak of mulla-mullung, medicine men and women whose power was tied to crystals.

One panel bears 96 sets of overlapping grooves, the earliest drawn horizontally, later intersected by vertical and diagonal lines. Two parallel sets of fine impressions—just 3 to 5 millimetres wide—suggest a child’s hands, positioned so high they must have been lifted.

Elsewhere, 262 grooves mark a low ceiling above a sloping clay bench. The patterns imply people balancing or crawling to press their hands against the glittering rock. Another stretch of 193 grooves traces a single direction above a creek bed, each indentation recording a step forward.

“These are gestures preserved in stone,” says the research team. “They are moments of deliberate action in a place set apart from ordinary life.”

For the GunaiKurnai, such caves were not dwellings but places where knowledge was practiced and passed on. The grooves, aligned with crystal-coated surfaces, resonate with this tradition. They are not merely “rock art” but records of embodied cultural practice—an exchange between human movement and the cave’s material power.

In Waribruk, the marks remain luminous under artificial light, connecting modern visitors to the actions of those who walked its dark passages millennia ago. Each groove is a trace of intent, of ritual, and of identity, anchored in stone yet alive in memory.

Related research:

Bahn, P. G., & Vertut, J. (1997). Journey through the Ice Age. University of California Press. [Cave art context, includes finger fluting parallels]

Sharpe, K., & Van Gelder, L. (2006). The study of finger flutings. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 16(3), 281–295. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959774306000173

Morwood, M. J., & Trezise, P. J. (1989). Edge-ground axes in Pleistocene contexts in northern Australia. Antiquity, 63(240), 354–358. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003598X00075965

Ross, J., & Davidson, I. (2006). Rock art and ritual: An archaeological analysis of Aboriginal rock art in western Arnhem Land. Australian Aboriginal Studies, (1), 54–65.

Gunn, R. G., Douglas, L., & Whear, R. L. (2010). What bird is that? Identifying birds depicted in rock paintings in western Arnhem Land. Australian Archaeology, 71(1), 29–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/03122417.2010.11689379

Kelly, M., David, B., Rivero Vilá, O., Garate Maidagan, D., Delannoy, J.-J., Mullett, R., Birkett-Rees, J., Petchey, F., Barker, A., Arnold, L. J., Green, H., Fresløv, J., & GunaiKurnai Land and Waters Aboriginal Corporation. (2025). Finger flutings at New Guinea II Cave, lower Snowy River valley (Victoria), GunaiKurnai country. Australian Archaeology, 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/03122417.2025.2529627